What do Barney Kessel and Audrey Hepburn have in common? Well, May is a significant month in both of their lives, but for entirely opposite reasons. Hepburn was born May 4, 1929. Kessel passed away after a long battle with brain cancer on May 6, 2004. They are also connected by Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which was released in October, 1961, the same month as Kessel’s birthday. Fans of the film’s music may or may not know that in 1961, Reprise Records released Kessel’s own version of Henry Mancini’s iconic score.

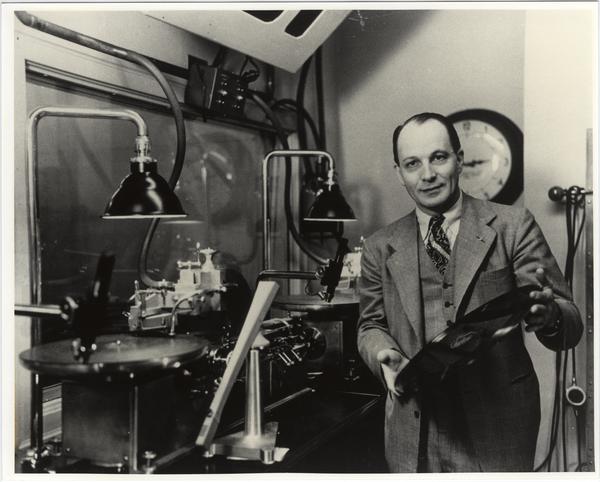

The iconic score of Breakfast at Tiffany’s is just one of Henry Mancini’s (above) accomplishments.

It’s not entirely clear how much Kessel was involved in making the original score. However, in the Kessel collection are original orchestra copies of Mancini’s arrangements. These would have been given to the members of the orchestra. Kessel either kept or somehow got these, and then used them to write his own versions of the songs. These items are valuable for music historians and musicians alike first because they are rare, and second because they demonstrate Kessel’s musical genius.

[ngg_images source=”galleries” container_ids=”6″ display_type=”photocrati-nextgen_basic_imagebrowser” ajax_pagination=”1″ order_by=”sortorder” order_direction=”ASC” returns=”included” maximum_entity_count=”500″]Here is a brief outline of what Kessel did differently. (Disclaimer: Yours truly is no music expert, and owes thanks to LaBudde Special Collections Graduate Student Assistant and Performance DMA student Anthony LaBat for helping to explain this.) Most noticeably, Kessel changed the instrumentation. He assimilated different parts from the Mancini score into parts for his versions. For example, in “Latin Golightly”, he assimilated the original Alto Sax & Trumpet, and Trombone & Baritone horn parts into a single part, which he played on guitar. Victor Feldman and Bud Shank also played that assimilated part on Vibraphone and Flute, respectively. For the bass, Kessel wrote an entirely new part that may have been modeled from the existing bass track, but was almost completely different in pitch and made rhythmic changes as well. In “Moon River Cha-Cha” Kessel again played the saxophone part on guitar, but he raised the pitch slightly throughout. Kessel was a master at chords, and chord harmonies. He made subtle adjustments like the ones in Moon River Cha-Cha to “revoice” chords. Doing this changed how the different chords in a progression pulled to one-another. In some cases it may have changed the entire progression. He also did this in “Sally’s Tomato” when he combined the trumpet and the alto sax into Bud Shank’s flute part. There was no dedicated flute part in Mancini’s original. Other changes include adding bongos to some of the songs, combining piano and guitar parts into rhythm guitar, using existing trombone fills for guitar fills between choruses, cutting out some bars, and recombining parts of choruses to make his own.

Also in the Barney Kessel collection is an original reference copy of Kessel’s album, which would have been made by the recording studio for band members. The full album was released on vinyl in 1961. Listen to the songs below and see if you can hear the differences, like the flute playing the original trumpet and sax part in Sally’s Tomato.

In Moon River Cha-Cha, compare the guitar, flute, and vibes in Kessel’s version to the saxophone in the original. Also, listen for the guitar playing the trombone fills – it starts at about 1:15 in both videos.

If you want to listen to any of the songs from Breakfast at Tiffany’s, we have multiple copies of both the Mancini originals, as well as the Kessel version in the Marr Sound Archives.

Sources:

Barney Kessel Collection, MS295, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Discogs