This spring, a new exhibit is opening in Miller-Nichols library and at locations around Kansas City. Titled “Making History: Kansas City and the Rise of Gay Rights,” the exhibit explores Kansas City’s surprising role in the US gay rights movement of the 1960s. The exhibit opened April 19 at UMKC’s Miller Nichols Library (800 E. 51st Street) and will be on view through September 30. If you want to learn more, you’ll need to see the exhibit. However, for a special post this week I thought I would share my perspective as one of the contributing curators. I can’t speak for everyone who worked on the project, but I hope my experience gives readers a taste of what its like to work with the “stuff” of history and turn it into an exhibit panel.

Most of the time, the history that you see in an exhibit or read in a book is just the tip of a very big iceberg. Historians deal in a particular type of story – we call them “narratives.” A narrative is a vehicle for explaining how and why certain events in the human past happened the way they did. We use narratives the way Physicists use models – to explain how and why systems work. In our case, our system is the whole of past human affairs and the narrative is a model for why some of the atoms (humans) behaved the way they did. Coming up with one of these models means balancing between staying true to the historical evidence and inferring something more from the evidence that makes it part of an interpretation. Having just the facts, with no interpretation or narrative, results in the dry “history” you hated in high school. Just a narrative with no supporting evidence? That’s called fiction. Good histories mix fact and interpretation, and also answer what we call the “so what” question. This asks why is what we have to say important? What lesson can be drawn from it, or how does understanding this part of the past allow us to understand a different part better? Sometimes, particularly challenging source material makes the entire process harder.

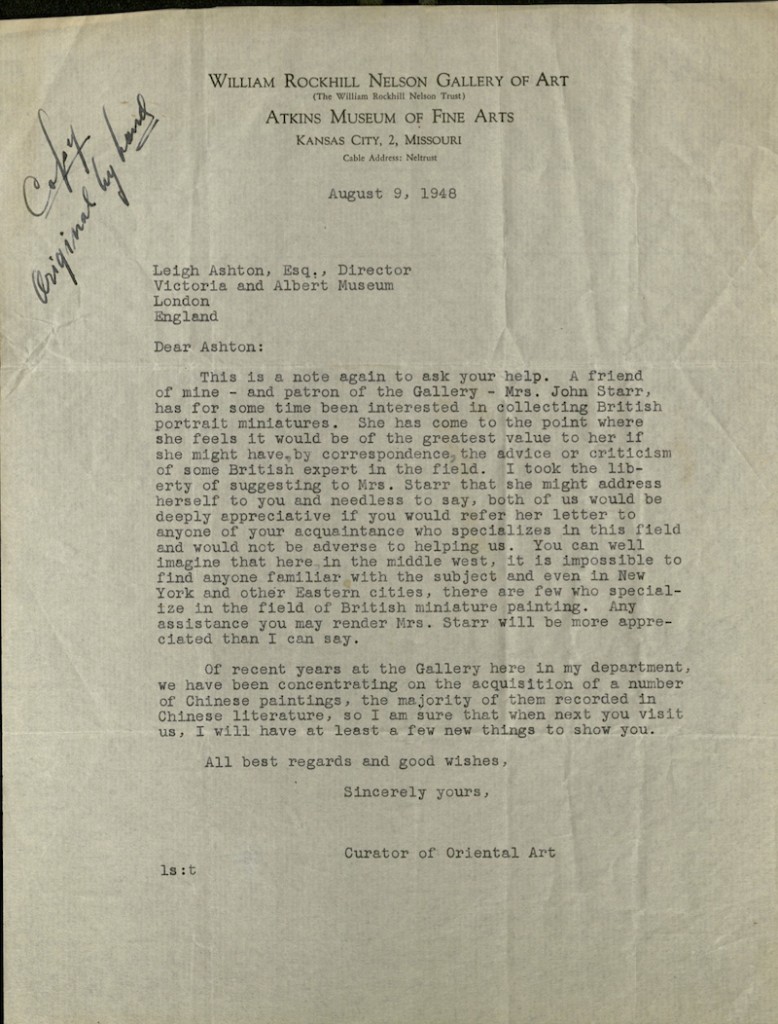

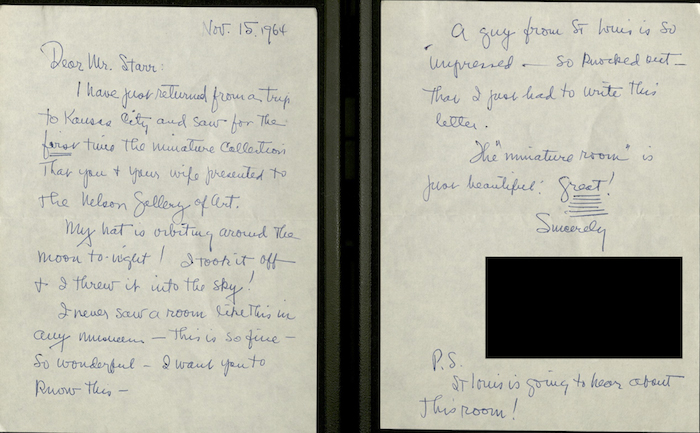

The most salient aspect of this project for me was the challenge my source material presented. My panel is about the Gay Bar scene in Kansas City in the 50s and 60s. The most amazing source material I had was a huge set of pictures taken at a few different bars.The problem I faced was a difficulty to do either one at all. In some cases these were just pictures of people. The subject, date, and location were unknown. Pictures of people at a bar is not history. I was going to have to make some judgements about what I was looking at and why it was important. On the other hand, these were like people’s Facebook photos. Who am I to draw any sort of conclusion about what they “mean” or what the “significance” is? I wasn’t there. I don’t know them.

Picture from the GLAMA collection, similar to the ones I worked with. The people, place, and date are unknown.

I’ve never been at such a loss about how to interpret a source, in part because I felt as if any interpretation violated someones privacy. Then I realized the answer lay in the problem: the intimacy of the photos was the lesson. These photos show how important gay bars were at that time because they were a place where people could be intimate, or could take pictures together without fear of repercussions. My panel presents the photos without telling you a great deal about who those people were. But it does tell a story about why gay bars were so important. If you ask me what these photos “mean” in an historical sense, I’d say they’re evidence that bars were special places for gays and lesbians in the 1950s and 60s. You can see it in the pictures they took.