One year ago, LaBudde Special Collections (LSC) and the Marr Sound Archives (MSA) made a valuable and historic addition to our collections through the remarkable generosity of Phyllis Kessel, widow of legendary guitar player Barney Kessel. Mrs. Kessel donated her late husband’s collection of nearly 400 audio/video items and hundreds of print documents. It turns out that one of hardest-working musicians to ever pick up a guitar was also a meticulous archivist. As a result, the Barney Kessel collection is a goldmine for music historians and fans alike. Through the efforts of LSC Graduate Student Assistant Anthony LaBat, MSA Public History Intern Taylor Bye, and the rest of the LaBudde and Marr team, we have finished processing the collection. This is the first of a series of posts taking a look at the breathtaking scope of Kessel’s career and offering a tiny taste of what the collection holds.

According to an official biography, “Barney Kessel was born in Muskogee, Oklahoma on October 17, 1923. He started playing guitar at the age of 12 and within a couple of years was playing in a local jazz orchestra. While he was still a teenager, Kessel met guitar legend Charlie Christian by chance in an Oklahoma City nightclub. Impressed by the youngster’s talent, Christian offered to pass his name on to renowned bandleader Benny Goodman. Christian’s guitar playing was a great influence on Kessel’s playing, which was essentially a further refinement of the older guitarist’s style. Kessel worked hard on his technique to create his own exciting, “straight-ahead” bebop jazz guitar, with no blues licks. Although he soon became well known locally as a talented guitarist, Kessel realized that there wasn’t a career for a jazz musician in Muskogee, and he moved to Los Angeles in 1942. Life wasn’t easy there and, at first, he had to make a living out of washing dishes at a restaurant, but he managed to get a break with the Chico Marx (of Marx Brothers fame) Orchestra in 1943, and this led to radio and studio work. A year later he appeared as the only white musician in an award-winning documentary film, Jammin’ The Blues. Word of Kessel’s abilities soon spread and during the remainder of the decade he also played with the bands of Artie Shaw, Charlie Barnet, and eventually Benny Goodman himself.”

By the 1960s, Kessel’s reputation was growing. In 1965, he made his first live record at P.J.’s Nightclub on Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood, just a few blocks over from the Sunset Strip. 1965 was right as the Sunset Strip was entering its heyday as an epicenter of American Rock & Roll.

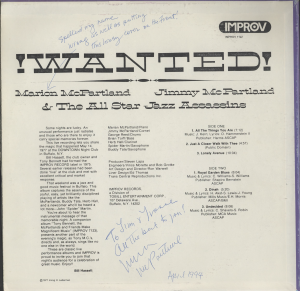

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3845054-1375225867-7212.jpeg.jpg)

Album Cover for On Fire (courtesy of Discogs)

Despite the burgeoning rock scene, clubs like PJ’s still catered to jazz audiences. PJ’s later became the Starwood Rock Club, before closing for good in 1981. Below are excerpts from a test pressing of his 1965 live show, which he released as the album “On Fire” on his own label (Emerald Records.)

Another singular item in the collection is what we believe to be an unreleased recording made for Reprise Records (part of Warner Brothers) in either the early or mid-1960s. The recording features Kessel playing alongside tenor sax whiz Zoot Sims. With Kessel and Sims were Monk Montgomery, Johnny Gray, and John Piscatelli on bass, 2nd guitar, and drums, respectively. According to a 1992 letter, Warner Brothers never released the album, though Kessel wanted them to release it as a CD. For copyright reasons, we can’t upload any of the material from that session. However, it is just one example of the unique items in the Kessel collection that researchers can use to uncover new stories about the history of American music.

Sources:

Barney Kessel Collection, MS295, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas City.

http://articles.latimes.com/1991-04-27/entertainment/ca-675_1_sunset-strip

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Starwood_(nightclub)

http://martinostimemachine.blogspot.com/2016/12/pjs-night-club-las-first-discotheque.html