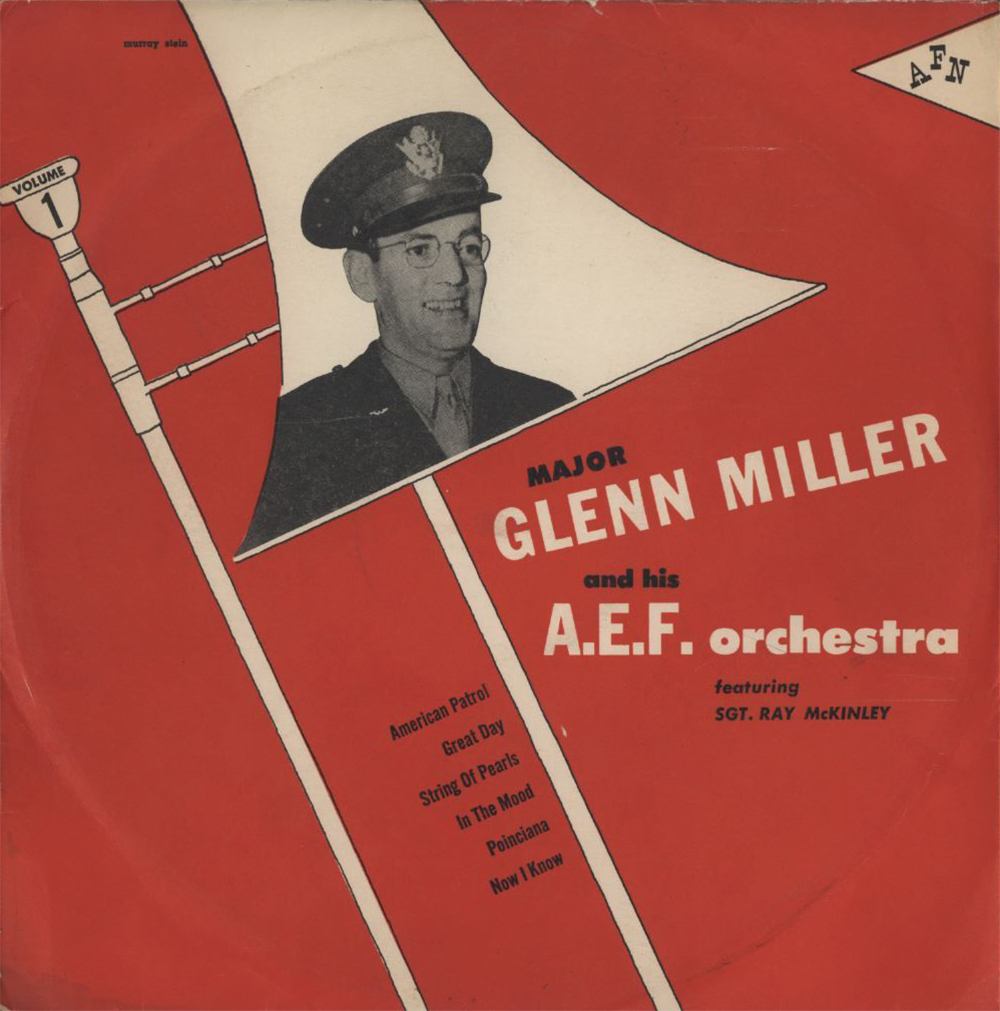

It’s probably 16 inches wide, and you hold it carefully by the edges. It could be made of glass or aluminum, coated with black cellulose nitrate. If you’re lucky the coating hasn’t started flaking off yet. Alternatively it might be made of vinyl, like an LP, but bigger. It plays at 33 1/3 RPM, holds 15 minutes of recorded sound, and was a key tool in the development of syndicated radio programming in the United States. We’re talking about transcription discs.

[ngg_images source=”galleries” container_ids=”2″ display_type=”photocrati-nextgen_basic_imagebrowser” ajax_pagination=”1″ order_by=”sortorder” order_direction=”ASC” returns=”included” maximum_entity_count=”500″]

In the 1920s, radio stations needed a way to replicate and share programming consistently. They weren’t allowed to play commercially released records on-air because musician’s unions believed that hurt record sales. So radio content had to come from somewhere else. Live broadcast was inconsistent, time consuming, and expensive. Not every radio station could afford to have its own in-house musical groups, but all stations wanted to attract more listeners. At this time the first radio networks were beginning to form. The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) was created in 1926, and Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) was formed in 1927. As these networks made more programming and acquired more satellite stations, they needed a way to distribute programming. Larger radio stations were creating programming of their own that they wanted to share with the networks. In short, there was a huge market for pre-recorded radio programming, but distribution of content was still a major hurdle. Transcription discs were the solution.

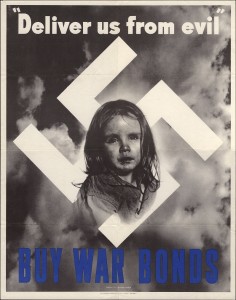

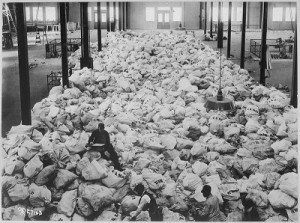

By the 1930s, transcription disc recorders had become ubiquitous at larger radio stations. Program producers were able to pre-record a program, make copies, and distribute it to other radio stations for future broadcast. This meant that stations in networks could all get the same programs. Individual stations could also add out-of-network programming to their repertoire by purchasing them from distributors. A station could also record its own unique local program using transcription discs, and then re-use it later. As a result, small stations could avoid the expense of live programs. Bigger stations and networks could get their shows to a wider audience. This meant listeners in Boston, Kansas City, and San Francisco could hear the same program at the same time. The ability share programming is a big reason why radio contributed to the growth of popular culture across America. To paraphrase Marr Sound Archives director Chuck Haddix, “radio was like the internet” because it brought people closer through information sharing. Everybody got to hear the same radio programs and news broadcasts, giving people similar cultural and political knowledge. We take this for granted today. Imagine for a moment a conversation with someone from two or three states away. They hadn’t heard Adele’s latest song or weren’t able to listen to that Ted Talk that enthralled you. Of course the opposite would be true as well. Its 75 degrees here in Kansas City. What snow storm in Ohio? That political protest in Washington that they went to? You had no idea until weeks later. Certainly newspapers allowed content-sharing, but radio was a huge leap forward, and it’s largely thanks to the humble transcription disc. One of the big 1930s radio stations that made a lot of transcription discs was KMBC here in Kansas City. Many of these discs are now held in the Marr Sound Archives.

KMBC joined CBS in 1928 as the 16th affiliated station. In 1930 station moved to the eleventh floor of the Pickwick Hotel. Under the direction of Arthur B. Church, KMBC became a model for other stations. Church and KMBC produced a wide variety of syndicated shows which were recorded on transcription discs and then distributed. One of these programs was the Texas Rangers. Another example from the KMBC collection that highlights the importance of transcription discs is a recording of one of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “fireside chats.” The recording can be heard below. It was made by CBS at the White House on May 2, 1943. It was then presumably broadcast by all CBS network stations, including KMBC. FDR could not have reached the entire country without transcription disc technology.

Sources

Museum of Broadcast Communications. Encyclopedia of Radio. Edited by Christopher Sterling. Vol. 3. London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2004.