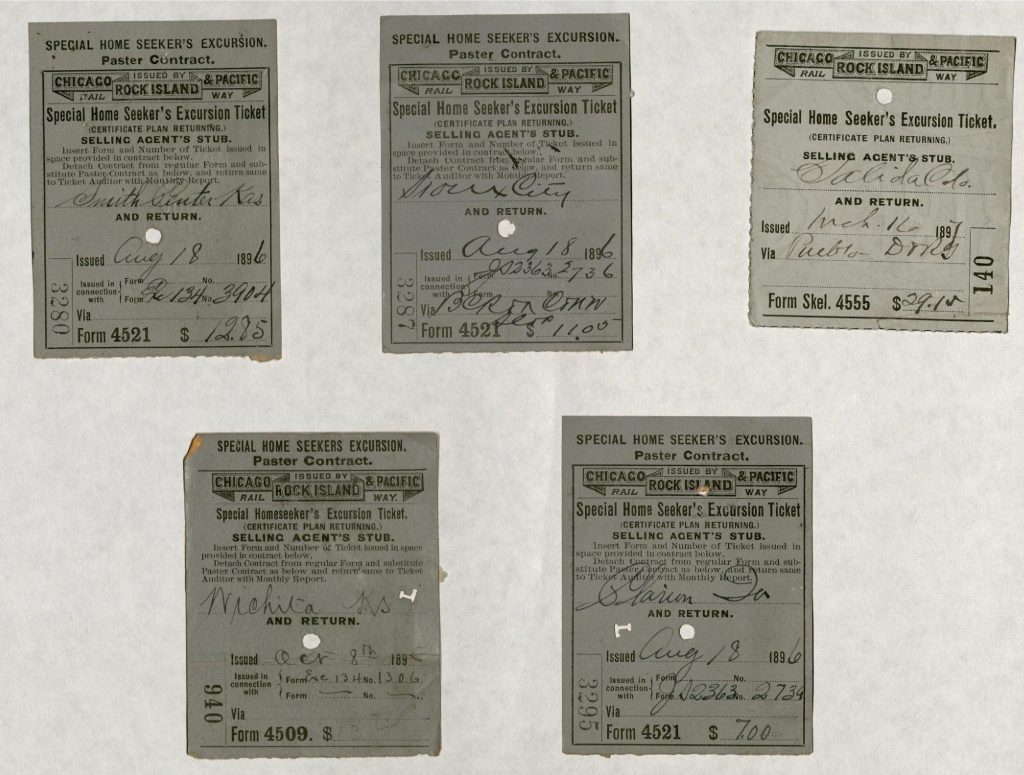

Imagine a young couple living in Chicago or Kansas City in 1896, who wants to move to a new city. Maybe he had a new job in a different city, or maybe they were adding to their family. Whatever the reason is, they needed to buy a new house somewhere else, which means they needed to go look at houses. They did not have a car, and even if they did there were few roads. Fortunately for our fictitious home-buyers, the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific railroad had a solution: a special type of ticket called a Home Seeker’s Package or Home Seeker’s Excursion. The J.E. Lynn Railroad Collection in LaBudde Special Collections has several examples of these tickets. In these unassuming tickets is a story of how railroads fueled America’s growth, one prospective home buyer at a time.

A variety of tickets to destinations such as Wichita, KS; Marion, GA, Sioux City, SD; and Salida, CO.

The so-called “golden age” of American railroads lasted from the late 1870s until the Great Depression. During this time trains carried up to 3/4 of interstate freight, and basically all of the passenger travel. Together with the great ocean liners, they were the pinnacle of early twentieth century travel. As a result, they were accessible to all kinds of people. There was greater diversity of schedules, more stops, and more variety of ticket packages than there are today. Furthermore, their pre-eminence made railroads an important part of America’s continuing growth and prosperity. Home Seeker excursions were one particular example of how railroads helped populations move across the country during this “golden age.”

When our young couple bought a home seeker excursion, they were getting a heavily discounted round trip ticket to a particular destination(s).

There was a set period of time to use the return half of the ticket. If the buyer missed their return date, the ticket was worthless. Most home seeker excursions took prospective buyers to newer areas. Texas, Oklahoma (which in 1900 wasn’t even a state yet), Nebraska, New Mexico (also not a state yet) and the Dakotas. Clearly, the US looked very different in 1900 than it does today. National priority #1 was to develop the lands that had been won from the French, Spanish, Mexicans, and Native Americans during the prior century. As the best-available means of land transportation, railroads were the best tool for accomplishing this. The home seeker’s excursion ticket reflects this. There were other ticket packages too, such as tourist or sightseeing excursions, as

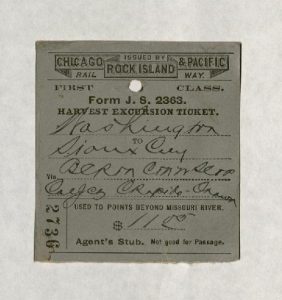

A Harvest Excursion ticket to Sioux City

well as harvest excursions. However, the home seeker excursions are particularly important because they illustrate the critical role railroads played in helping fill the empty parts of America. When the transcontinental railroad was being built during the 1860s, much of the rhetoric was about tying the country together. A lot of railroad development was subsidized by federal and state governments, and it is possible that is why home seeker tickets were relatively cheap. While it is easy to be cynical about such a union of naked capitalism and nationalism, it is not clear if such a robust rail network could have existed otherwise. That rail network is what enabled much of America’s growth prior to the Depression. One way was by making it easier for people like our fictional family to migrate to new parts of the country.