On this blog we’ve already covered a little bit of Barney Kessel’s work on film music, discussing how he adapted composer Henry Mancini’s score for “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” into his own record. However, Kessel’s involvement in film dates back to at least 1944 when, at the age of 21, Kessel played guitar in the Warner Bros musical short “Jammin the Blues,” released May 5 of that year. In the Barney Kessel collection are 2 records with music from the film, as well as a 38-page interview in which Kessel discusses the film, its origins, its impact, and the backstory of many of the artists involved. Kessel was proud of his role in the film – its musical style was close to his own musical roots and playing in it was a big step forward in his own career. The film itself is only 10 minutes long. In 1995, the Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the United States National Film Registry because the film is “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”. Turner Movie Classics, which has aired the film as part of a tribute to the National Film Registry, called it “one of the greatest of all jazz films.”

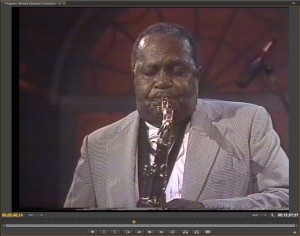

According to a 1982 interview, Kessel explained that the film came about because Jazz producer Norman Granz (right) wanted to recreate on film the jam session music format he had helped popularize in the Los Angeles jazz scene in the 1930s and early ‘40s. Granz selected an impressive roster of musicians for the film. The list of performers included Lester young (Tenor Sax), Red Callender (Bass), Harry Sweets Edison (Trumpet), Marlow Morris (piano), Kessel (guitar), John Simmons (Double Bass) Illinois Jacquet (Tenor sax) Marie Bryant (vocals) and Sid Catlett and Jo Jones (drums). Kessel recalled that he became involved with the film because he was one of few musicians playing electric guitar in Los Angeles at the time. He had been a regular in many of the local jazz clubs, and already had a strong reputation with Norman Granz.

According to a 1982 interview, Kessel explained that the film came about because Jazz producer Norman Granz (right) wanted to recreate on film the jam session music format he had helped popularize in the Los Angeles jazz scene in the 1930s and early ‘40s. Granz selected an impressive roster of musicians for the film. The list of performers included Lester young (Tenor Sax), Red Callender (Bass), Harry Sweets Edison (Trumpet), Marlow Morris (piano), Kessel (guitar), John Simmons (Double Bass) Illinois Jacquet (Tenor sax) Marie Bryant (vocals) and Sid Catlett and Jo Jones (drums). Kessel recalled that he became involved with the film because he was one of few musicians playing electric guitar in Los Angeles at the time. He had been a regular in many of the local jazz clubs, and already had a strong reputation with Norman Granz.

Granz allowed the musicians to choose their own songs for the film. Kessel recalls that Director Gjon Milli encouraged he and the other musicians to dress and behave as they would if they were going to play a regular show. The way the film was made was by first recording the music to be used in the film, and then filming the musicians playing along to the music as it was played back to them. Years later Kessel chuckled at how the musicians couldn’t always recall exactly what they had played during the recording sessions because it was very improvisational. When it came time to simulate playing along with the recording, the two didn’t always match up.

Most notably, and somewhat controversially, Kessel was the only white musician in the film. Granz was trying to advocate for the end of segregation in music, both for audiences and band members. He took the same approach with Jammin the Blues, to the dismay of Warner Bros mogul Jack Warner, who insisted that a black guitarist be found to make an all-black band, lest the film perform poorly in the segregated South. Granz refused to do so. Kessel described Granz as a real proponent of music as a meritocracy – Granz believed using a black guitarist to keep the film’s band from being integrated was just as racist as any other segregation. Either you could play, or you couldn’t, and Granz would have no one who couldn’t play. The compromise reached was to hide Kessel in the shadows.

Kessel’s entire recollection of the film is a positive one. “Of all the things I’ve done [in film]”, he said, “that was the most relaxed.” He liked how the Gjon Mili and Granz did not manipulate the performance – instead they “captured what’s going on” and presented it naturally. Compared to the music and film of the 1970s and 80s (he was interviewed in 1982) Kessel thought that the artistic value and quality of Jammin the Blues was twice as good. Kessel was a man of strong opinions, and he clearly had a high opinion of the film and his fellow musicians, especially Lester Young. He believed that the film captured a particular moment in music history, one that was driven both by the innovative producers like Granz and performers like Kessel and Lester Young who together made some of the best music of that or any other era, and also defied the racial mores that still hamstrung black men and women in much of America.

Sources

Barney Kessel Collection, MS295, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas City.

![From the verso of the photo: "Christmas Dreams Jackie Cooper, the youngest Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer star, enj[oys] the dream on Christmas Ever almost as much as he does the actual happenings the next day. Jackie, who will next be seen in “Buddies” with Buster Keaton and Jimmie Durante, evidently hopes for a boat."](http://info.umkc.edu/specialcollections/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/buddies-011000w-237x300.jpg)