Above: Rittenhouse Square, Philadelphia. Source: Wikimedia

It’s not as simple as installing nice park benches (though that’s part of it)

In last week’s posts, my studiomates and I — having just been “introduced” to the system earlier in the week — posted our “first impressions” of Kansas City’s fabled Parks and Boulevards system, the focus of this semester’s design studio.

As was pointed out in those posts, half of us are from here and have been in contact with the system at least on and off all our lives: we weren’t posting our “first” impressions, more our understanding of the system based on a couple decades of experience.

But regardless of whether we were native Kansas Citians or not, a certain theme appeared in most of our posts last week. We each generally focused on a particular part of the system — usually, a specific park we had visited recently or were familiar with. The sites we were studying were different, our perspectives were different — and yet a theme emerged: that Kansas City’s parks and boulevards aren’t living up to their potential.

It was a sobering conclusion: that one of our city’s most distinguishing physical features isn’t fulfilling its function (and this finding was compounded by the realization that we each found the same thing). Parks are meant to have people in them, right? Yet, there were few — sometimes no — people in any of our studied parks. Boulevards, a somewhat trickier feature to study and measure the success of, certainly were driven on, we found — but we also saw that a whole other dimension of amenities offered by boulevards beyond their attractive landscaping — including shelters, monuments, open areas for sports — seemed to have been lost on Kansas Citians.

So what’s the problem? There was some chatter among us that, well, maybe it was the weather — we had initially visited our parks on a chilly January day, after all. But then some of us got back out on an unseasonably warm day later in the week and essentially saw the same. Maybe it was the time of day, or the fact we surveyed mostly on weekdays — even the best park’s going to have some ebb and flow. But over the last week, we’ve gotten out at various times of day, and even over the weekend, only to find most parks mostly empty. (And anyway, some of us were basing our judgement on years of observation and experience of these parks.)

No, for these underused parks, it seems there has to be some environmental characteristic of them — or possibly of the city around them — that was keeping people away.

A Kansas City Specific Problem?

Of course, we can all picture well-used parks. My mind jumps to parks I’ve experienced while visiting bigger cities — Chicago, Montreal, and recently in Buenos Aires. As a Kansas Citian, some of these places were striking in how busy they were: so many people, young and old, doing all kinds of things — playing on swingset, throwing a frisbee, jogging, sitting, or just walking through.

Obviously, there are examples of well-used parks here. Everyone’s been to Loose Park. Mill Creek Park, with it’s horse fountain in the shadow of the ever-popular Plaza, is busy on balmy weekends and even weekday lunchtimes. A certain part of Gillham Park gets packed on a nice weekend day. Penn Valley and Swope Parks will usually have some kind of traffic on the weekends, regardless of weather (though these are regional parks, and I’m concerned here with smaller, more “neighborhood-oriented” parks).

But those are really just a handful. The Kansas City Parks and Boulevards System comprises “12,000 acres of parkland including 220 parks,” according to the parks department (2014). (That’s about 26 acres per 1,000 residents, which is about the median for US cities of our size [Trust for Public Land, 2011].)

Kansas Citians do seem to care about their parks system as a whole. In 2012, residents passed a sales tax dedicated to the maintenance and expansion of their parks system — this funding had previously just come from the property taxes funneled through the City’s General Fund.

So it’s not lack of interest that keeps so many KC parks empty. It’s not oversupply of park. And it’s not their condition — most parks here are very well kept. So, in short, it doesn’t appear to be something about the city, its residents, or the parks system as a whole that’s responsible.

Meanwhile, let’s keep in mind that even in cities with really great parks — Central Park, Millennium Park — there are always forgotten, empty parks.

So then, it’s not necessarily a Kansas City-specific issue — all cities can struggle to fill their parks.

That raises the question, then — what is it that makes a great park? Can we identify particular elements of urban and park design that lead to a busy park?

What makes a great park (or boulevard)?: The Jacobs/Whyte Formula

Luckily for us, we can turn no further than to the great Jane Jacobs for some answers. She devotes a chapter of her seminal Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) to “neighborhood parks” (so, again, not regional attractions like Swope or Penn Valley).

Actually, though, Jacobs may not be the most prominent figure in the study of parks in the US — William Whyte, founder of the discipline of urban psychology, put together a widely respected analysis of parks in New York City that was turned into a film, as well as a chapter of his 1988 City: Rediscovering the Center (1996, 483).

Combine Jacobs and Whyte’s work and you end up with a powerful rubric for analysis a city’s parks.

Jacobs: “Diversity”

Jane Jacobs was all about upending conventional thinking about cities and urban planning of her era. In the Death and Life chapter entitled “The uses of neighborhood parks”– well, she might as well have stopped writing after the first two sentences:

Conventionally, neighborhood parks or parklike open spaces are considered boons conferred on the deprived populations of cities. Let us turn this though around, and consider city parks deprived places that need the boon of life and appreciation conferred on them. (1961)

Walk-off homerun, right there.

Basically, Jacobs says that parks are often created to become site of diverse activity with a diverse group of residents. Yet, she argues, what makes a park successful in this way is diverse activity already happening in the area. A vibrant, successful park, in other words, comes from a vibrant, successful neighborhood — not the other way around.

Jacobs uses a set of very similar parks around downtown Philadelphia for a sort of experiment to test this hypothesis. She explains:

Philadelphia affords almost a controlled experiment on this point. When [William] Penn laid out the city, he placed at its center the square now occupied by City Hall, and at equal distances from this center he place four residential squares. What has become of these four, all the same age, the same size, the same original use, and as nearly the same in presumed advantages of location as they could be made?

Their fates are wildy different. (1961 p?)

The four squares, basically copies of each other, turned out differently based on the conditions in the neighborhoods immediately surrounding them. The figure below summarizes her findings:

Jacobs essentially says that a park — after all, a relatively passive place — will mirror its surroundings.

And key to the continued success of a park is not only the quality of the neighborhood around it — whether it’s a “good” or “bad” place — but it’s also diversity of uses in the surrounding neighborhood that’s important too.

As Jacobs describes 1950-60’s Downtown Philadelphia, the areas around Rittenhouse Square and Washington Square are prominent, busy district — the latter is home to high-profile commercial office towers. The difference between the two is the degree of diversity in activity. Rittenhouse Square has around it, not only residences but “an art club with restaurant and galleries, a music school, and Army office building, an apartment house, a club, an old apothecary shop, a Navy office building… (1961 p?)” The list goes on.

What does this mean for the park? “This mixture of uses of buildings directly produces for the park a mixture of users who enter and leave the park at different times.”

And Washington Square? “Its rim is dominated by huge office buildings, and both its rim and its immediate hinterland lack any equivalent to the diversity of Rittenhouse Square — services, restaurants, cultural facilities. (1961 )” Consequently, the only significant population who would use the park are office workers from the surrounding buildings, describes Jacobs, and they are only free at lunchtime. And the relative “vacuum” of space that is created is filled by undesirable characters who end up scaring a lot of the office workers off altogether. This park, now known as Washington Square Park, shares some eerie similarities with Kansas City’s park of the same name near Crown Center.

“Design:” Whyte (and Jacobs, too)

I was prepared to set Death and Life down and begin work on my final project right then, after reading the results of Jacobs’ Philadelphia experiment: the “diversity” explanation seemed so spot on.

And there’s nothing to suggest that Jacobs was anything but spot on there. But even she added some detail to what makes a great park — this time, focusing on the specific design elements of a park. After all, the most vibrant neighborhood around just a plot of mowed grass probably wouldn’t make for the best park.

Jacobs defines four elements integral to the success of a neighborhood park:

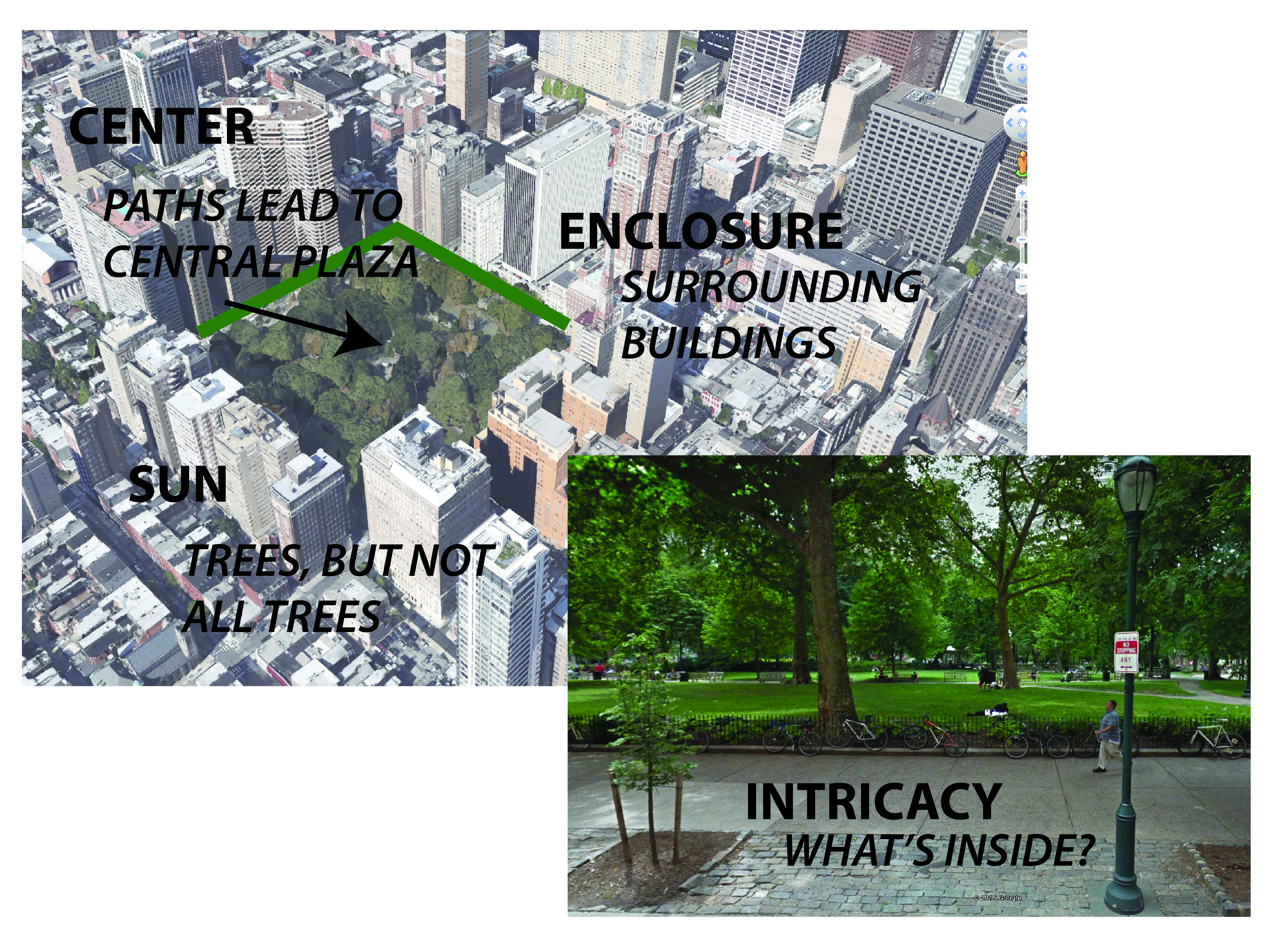

1. Intricacy: A complex, interesting plan. “[C]hange in the rise of ground, groupings of trees, openings leading to various focal points… (1961)”

2. Centering: A well-defined center point, something that pulls people into and/or through the park. Jacobs criticized “[l]ong, strip parks” especially for generally lacking a center, which she says leads to confusion among park users as to where they should go.

3. Sun: A balance of sun and shade. Too much open space exposed to the sun without trees for shade is bad; so is a giant, chilly shadow cast by a building.

4. Enclosure: Usually by surrounding buildings, making a “definite shape out of the space, so that it appears as an important event in the city scene… (1961 )”

Rittenhouse Square embodies these four characteristics.

A mixture of two or three of these criteria could be attributed to Kansas City’s best parks (most are probably going to lack strong “enclosure,” though, due to our low density). Loose Park has intricacy, centering, and a good mixture of sun and shade (and some enclosure). Gillham Park has intricacy, sun, and even enclosure. (Penn Valley and Swope Park, while popular, aren’t exactly neighborhood parks, so it’s unsurprising they defy Jacobs’ standards, lacking centers and enclosure and just being somewhat chaotically organized.)

Most parks in KC, though, are missing most of these elements. Many parks, lacking intricacy, can be taken in with a single glance, usually consisting of an open, uninspiring lawn, with maybe a path or playground on the edge. An that focus of elements on the edge — probably to be near parking — leads to a lack of centering of anything (except the lawn?). Addressing the sun may be what Kansas City’s parks do best, but even some parks lack trees or shelters at all. Very few parks here are enclosed, and many just melt into their surroundings, never declaring themselves as a distinct destination; some parks are defined by a line of distant trees along their back edge, but that effect is actually somewhat unsettling (what’s lurking there?).

Jacobs’ design criteria, seem, on the surface to explain the popularity (or lack thereof) of Kansas City’s parks. But really what’s that different about Loose Park and Budd Park? Is Loose’s Rose Garden and pinic pavillion enough to attract that many more people?

William Whyte’s design standards for good park space mostly affirm Jacobs’. His survey of New York City plazas in the 1970s found the most popular created visual interest (intricacy) with multiple levels, stairs, fountains, etc.; they got a good mix of sun and shade; they had centers, or at least defined nodes; and they had defined edges.

Whyte added several new findings to the understanding of park spaces, though. He and his fellow researchers, intricately mapping the flow and displacement of people in public spaces in New York City in the 1970’s, established two key patterns. First, they found that some of the most popular plazas were the most central, located closest to the largest office buildings. (This dovetails to some extent with Jacobs’ “diversity” argument.) Whyte qualified this, though: “Our initial study made clear that while location is a prerequisite for success, it no way assures it. Some of the worst plazas are in the best spots…. (486)”

The absolute defining factor, though, was the amount of sittable space in a plaza: “People tend to sit most where there are places to sit (487).”

And, in fact, more so than really any parks in Kansas City, two of the city’s most popular parks — Loose and Mill Creek Parks — or rather, the most popular parts of these parks are both centrally located in the city (near the busy Plaza) and they offer plenty of places to sit. At Loose Park, there’s the pavilion, the Rose Garden, each with plenty of benches; at Mill Creek Park, benches surround the iconic fountain at the south end of the park, and plenty of people just take a seat on the fountain’s generous rim. Many people walk to these parks — though most probably still drive.

But if all of this is the formula for good parks in Kansas City, the city soon starts to complicate things by introducing another element to its parks system: boulevards.

Boulevards

Jacobs’ and Whyte’s rubric might not, at first look, seem to be applicable to the spaces created by Kansas City’s numerous boulevards and parkways. (How can you even define a center/node for a street?)

Actually, though, Kansas City’s boulevards do meet many of the design criteria defined by Jacobs: To some degree, they create enclosure and intricacy, and manage sunlight well.

What they usually lack is the surrounding diversity of uses that Jacobs claims made Rittenhouse Square work so well: KC’s boulevards, after all, run through chiefly residential areas.

Meanwhile, Kansas City’s boulevards do not generally offer a place to gather, or just to be in. There are no places to sit. (Rare exception: The Black Veterans Memorial, in the median of Paseo near 9th St. Problem: lack of surrounding diversity of use.) Boulevards are places to drive or walk through, moving from an A elsewhere to a B still somewhere else.

Another notable “Jacobs” involved in planning research, HB Jacobs, provides a possible alternative for Kansas City’s boulevards. Jacobs wrote a compendium of great streets from around the world, aptly entitled Great Streets (1995).

One example he illustrates, that of Unter den Linden, a boulevard in central Berlin, checks all the boxes in the Jacobs/Whyte rubric: a diversity of uses is evident in the mixed-use building on the left in the photo above; expand the photo, and you’ll see that benches line the edges of the central median; meanwhile, the boulevard’s central location in the city probably helps make it successful. ( Jacobs adds: “The lindens are uniformly, 8 meters apart; the smell is beautiful, a reason to go there (148).”)

Ward Parkway, the median of which looks about as wide as Unter den Linden’s, will never look much like this photo otherwise.

What it — along with Paseo, Broadway, Benton — could become that is like the Unter den Linden above, is more of a place for people. That doesn’t mean tearing up all the grass in the median and verge for gravel pathways — but it could mean adopting some of the design elements I’ve already discussed. How about benches placed in the medians at major intersections with other streets? It would be a start. And where our boulevards do, in fact, mix with diversity of use — like, along much of Broadway Boulevard — sidewalk seating for likes of restaurants and cafés is not only doable, it seems imperative to attracting people to simply be in the street.

The real challenge: Turning these lessons into action in KC

In truth, a lot of what Jacobs and Whyte discuss seems to not be applicable to Kansas City. We’re not Philadelphia or New York. Few of our parks are the squares discussed by Jacobs or the plazas surveyed by Whyte. We could never live up the sketches of European boulevards in HB Jacobs’ Great Streets.

Yes, our parks (and boulevards) are somewhat different creatures.

But the theme common to the great examples of planning/urban design I’ve shared here is that those spaces are made for people to be in. And the reasons they attract people — a center node, plentiful seating, well-defined edges, etc. — still seem to ring true.

That implies many of Kansas City’s parks — which lack these elements — could use a redesign.

The most elaborate overhaul of our city’s parks wouldn’t matter, though, if we didn’t a better job of putting parks where people are. But then, remember — parks mirror their surroundings: safe, vibrant parks will only exist in safe, vibrant neighborhoods.

And if that’s accurate — well, we have a lot of work to do in Kansas City, and parks really become the least of our worries.

References

Jacobs, HB. 1995. Great Streets. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jacobs, J. (1961). Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York:Random House.

KCMO Parks & Recreation Dept. (2014) “About KC Parks.” KCParks.org. From http://kcparks.org/about-kcpr/

Trust for Public Land (2011). 2011 City Park Facts. PDF. From https://www.tpl.org/sites/default/files/cloud.tpl.org/pubs/ccpe-city-park-facts-2011.pdf.

Whyte, William H. “The Design of Spaces” as reprinted n LeGates and Stout’s (1996) City Reader, NY: Routledge.

Great post, I dig the diagrams as well. Yet, one of the issues Jacobs discusses is an over supply of parks being an problem. I feel like KC has an over supply of parks that strive to be the same. In a word, they lack diversity. They almost seem to attempt quantity over quality.

Totally agree on the “quantity over quantity” idea.

I mention briefly that KC’s just about average in terms of park acreage per number of residents (for a city of its size & density). At first, that suggests we don’t have an oversupply — but then, who’s to say each of these other cities doesn’t have an oversupply problem, too? All that “being average” means is that we’re normal — what if it’s normal for US cities to have a glut of green space?