Before planning the placement of a park, plaza or street in a neighborhood, the relation between all 3 elements, plus surrounding architecture, should be taken into consideration. The observations of 20th century activists and journalists on urban studies, such as Jane Jacobs and William H. Whyte, can be used as guides for modern designers, as insight from the past is often the foundation of new concepts. And although ideologies, technologies and living standards have changed over time, some things remain more constant than others – including the basic human need to enjoy outdoor spaces. Whether socializing in groups, in pairs, or singularly watching interactions take place around one’s self, people like to feel safe and comfortable while engaging in these activities.

“Knowing street sizes alone and what is in them is a major step in determining what is possible.” – H.B. Jacobs

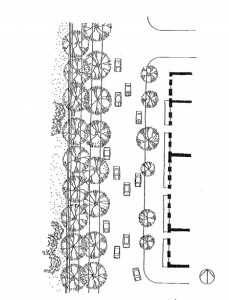

H.B. Jacobs’s comparisons of ‘great streets’ in the U.S. to examples in European cities show similarities and differences in how various planners think, and in their ideas of what a successful street is comprised of, when juxtaposed with parks and buildings. On the Ringstrasse in Vienna, Austria, the positioning of trees and pathways on the border of a park created a natural extension to the park, much in the way that strategically placed benches and low walls give visual access to pedestrians passing New York City’s Central Park on Fifth Avenue. Both designs used elements that complimented the areas’ surroundings to attract visitors.

http://www.plataformaurbana.cl/archive/2012/08/28/%C2%BFquien-es-jane-jacobs/

“The main problem of neighborhood park planning boils down to the problem of nurturing diversified neighborhoods capable of using and supporting parks.” – Jane Jacobs

A common misconception about parks is that they are placed in neighborhoods to ‘save’ them, in a sense; parks are expected to be elements that keep communities alive and anchored. Activist Jane Jacobs wholeheartedly disagreed with that notion. In ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities’, she argues that the opposite is actually true: people are the ones who add life and interest to parks. The types of people that frequent parks, and their patterns of use, are the main factors that give parks either a positive or negative vibration and aesthetic. In other words, parks don’t support people. People support parks! Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania shines as an example of a successful park, because the neighborhood surrounding it is filled with people of diverse lifestyles. Mothers and children, working people, students, etc. frequent the park at different time periods; the varying demographic groups filter in and out of the park in cycles, creating a balance of use.

In stark contrast, Philadelphia’s Washington Square had to be closed and redesigned in the 1950s, because the amount of crime had become unmanageable for the police. This degeneration of the park was caused by the lack of regular visitors; Washington Square was surrounded by office buildings, whose inhabitants were workers with (more or less) the same daily schedules. Thus, the variety and frequency in visits to the park were virtually non-existent, and eventually, vagrants made themselves comfortable there. Jane Jacobs made an interesting point when she stated that the park was not ‘taken away’ from other users by the homeless, but rather they discovered an abandoned park, and made use of it.

http://fab.cba.mit.edu/classes/4.140/people/jgeis01/week01.html

“People tend to sit most where there are places to sit.” – William H. Whyte

The Street Life Project was a study conducted by sociologist William H. Whyte, to analyze how people utilize urban space. With the help of designers, planners and students, he filmed the activity of parks and plazas around New York City, and developed surprisingly simple conclusions based on the patterns he found, which was documented in his film “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces”. The purpose of the observations was to answer a key question: What attracted people to plazas/parks? Although William Whyte believed that the location of a space was a prerequisite for success, he knew that an ideal location was not a guarantee that the space would thrive.

The activity seen at the study sites showed definite patterns in every day social interaction. People on their lunch breaks were the main focus on some plazas; factors such as sun angles, views and personal comfort guided every movement. William Whyte noticed that women were more discriminating than men when choosing where to settle in a plaza, and so it was safe to assume that a space with a higher ratio of women to men was probably well-managed. All of the spaces studied were located on major avenues or ‘attractive side streets’, and where there were ledges or steps near the sidewalk, men usually sat closest to the outer borders, while women gravitated towards spaces that were further back.

Out of all the positive aspects that were recognized in New York City’s parks and plazas, one feature bore the most significance. Of course, basking in the sunlight re-energized and uplifted the peoples’ spirits, splashing in water features relieved the stress of their morning work schedules, and stopping for lunch at food carts quelled their momentary hunger. But… if there was no place to sit and enjoy these amenities, would they be as popular? It is highly improbable! Seating was discovered to be the feature that attracted the most people to parks and plazas. Unconventional seating, like low walls, stairs and even sculptures, were used just as much (if not more so) as chairs and benches.

It is evident that the problems that arise when planning neighborhoods is rooted in the practice of separating a single element to plan, then trying to plan all other elements around it. All components of a neighborhood system reflect and depend on each other, as seen with parks, plazas and streets; when one part experiences trouble, there is always at least one other link that is affected as well. Conversely, one thriving element will positively effect another, which will eventually bring favorable results to the community as a whole, in one way or another.

Sources:

1. “A Compendium of Streets: Streets That Teach”. H.B. Jacobs

2. http://www.plataformaurbana.cl/archive/2012/08/28/%C2%BFquien-es-jane-jacobs/

3.http://fab.cba.mit.edu/classes/4.140/people/jgeis01/week01.html