Urban design can often play an important role in the public realm. It’s ability to influence personal behavior and its effect on social interaction are feats in and of themselves. Based on the ideas of congregation and movable chairs, American Urbanist William Whyte, is profound in the way he approaches urban space. In his documentary, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, Whyte examines the design of public spaces and how they influence social behaviors among their visitors. Public spaces are for people, clearly, but the ways people respond to these spaces are varied. Whyte’s dawn-til-dusk observation revealed many usage patterns, including time of day, gender ratios, and varied durations of stay. But what was it that deemed one park more successful than the other in Whyte’s study? In many instances, it was a matter of quality over quantity — meaning that the human appeal of a public park isn’t necessarily relative of its size, but rather its level of versatility. To put it lightly, if a person feels the desire to sit on the edge of the fountain, then you better make sure the fountain ledge is low enough.

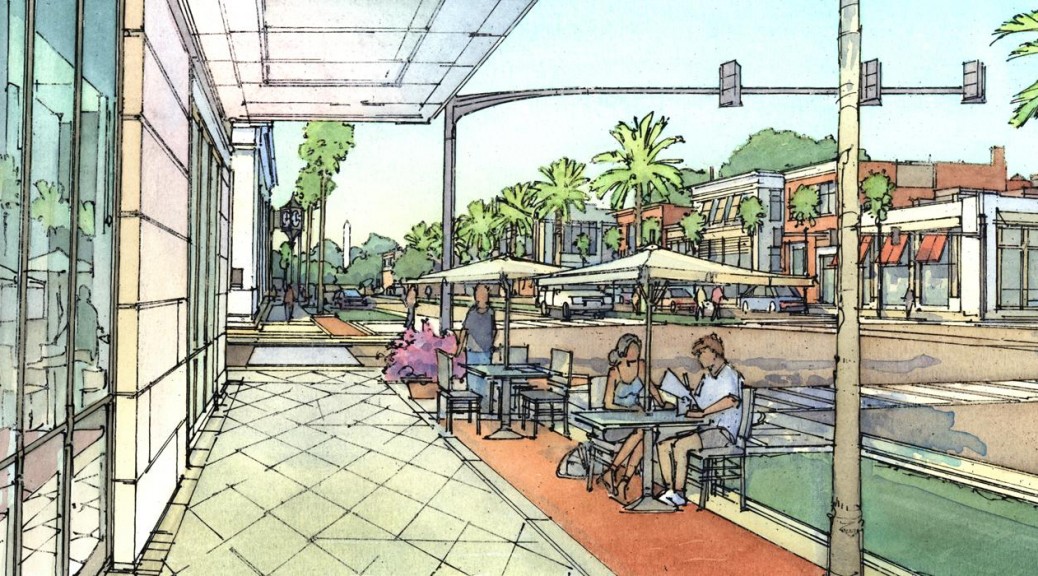

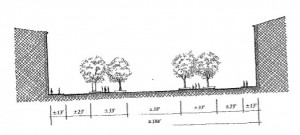

No different than some of Whyte’s thoughts, the ideas of H.B. Jacobs expressed in Great Streets reflect the influence of streetscape design on social behavior at the pedestrian scale. The use of street plans and cross sections accurately display the relationship between pedestrians and the buildings surrounding them. Different characteristics of the streetscape, including street width, the presence of vegetation, or even the placement of building entrances offer various influences on pedestrians. Although a particular street may be overly generous in width, much like Jacobs’ diagram of a Barcelona streetscape, the presence of vegetation helps break up space, and offers a sense of intimacy, despite the nearly 100 foot right-of-way. Similarly, the use of large glass panes, and strategically placed entrances offers a sense of permeability to pedestrians, and serve to keep human traffic flowing along the streets, in and out of buildings.

Jane Jacobs, in her book titled The Death and Life of Great American Cities, describes aspects of public parks that mirror many ideas of both Whyte and Jacobs. Described as volatile places, which exhibit complex behavior of extremes in popularity and unpopularity, Jacobs notes several examples of successful parks: Rittenhouse Square, Rockefeller Plaza, or even Washington Square. However, she also notes their counterparts, which she labels as city vacuums. So what is it that distinguishes a Boston Common from a city vaccuum? According to Jacobs, it seems to be the misconception of park behavior. Although examining park behavior is helpful, it is misleading to say that generalizations about human behavior can adequately explain all attributes of a single park. Therefore, it is imperative to look at park behavior relative to its location in the city. Take for example, Philadelphia, a central square, flanked on all four sides by smaller residential squares. All four the same age, yet, a drastic difference in fate — or in some cases, demise. The most successful of the four, Rittenhouse Square, is predominately influenced by its central location within a thriving neighborhood. Franklin Square, or Philadelphia’s Skid Row, is influenced not only by the groups of homeless and unemployed that gather, but also by the mix of flophouses, motels, and tattoo parlors that surround. Washington Square, a once downtown hotspot, has since transformed into the “Pervert Park”, influenced by high crime among the surrounding area. The fourth, Logan Circle, has transformed from a prime example of City Beautiful planning, to a traffic circle, which serves as nothing more than a point of interest for passing motorist.

Together, the opinions expressed in these writings suggest one thing — Urban design is an important role in the public realm. What does this mean for Kansas City and the 21st Century Parks & Boulevards? It’s simple, if we want people to use the parks we build, then we must build parks that people want to use. If we plan to revitalize this system as the transit backbone for motorists, cyclists and pedestrians alike, then we must, at the very least, consider these opinions and characteristics. Given that multiple parks and boulevards intersect at various points throughout Kansas City, it is important to realize each park independently susceptible to many factors that determine its behavior. In order to provide a consistently enjoyable experience across the parks system, all of these factors must be taken into consideration, otherwise, similar to what Jane Jacobs stated, we’re doomed to having parks where there are no people, and people where there are no parks.

Sources:

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, (1961)

H.B. Jacobs, A Compendium of Streets: Streets That Teach

William H. Whyte, The Design of Spaces, (1988