As you’ll read in other posts here, several of us in this studio are natives or long-time residents of the Kansas City area. So, like for them, these aren’t exactly my first impressions of the Parks and Boulevards. Instead, they’re impressions based on two decades of living here and experiencing – or, as you’ll read below not experiencing, in a sense – the system.

Several things are important to point out about the Parks and Boulevards system, especially from the perspective of native: first, there’s a myth and a separate reality about the system; second, besides this cognitive disconnect, Kansas Citians seem physically disconnected with much of the system — a lot, if not most, of it doesn’t get used, as you’ll read below. The system exists as a type urban legend to many Kansas City — we’re largely unaware of all it has to offer.

We get to take on that challenge this semester and work to reconnect the city to one of its best features.

The Myth

The Parks and Boulevards system is part of the shared experience of Kansas Citians. It’s an urban legend, in the sense that it’s passed on through the common spoken narrative, like creation stories and myths are shared across thousands of years among members of cultures around the world. We understand as young Kansas Citians that our Parks and Boulevards are something special – or at least are supposed to be. New York has its Central Park, St. Louis, Forest Park; but Kansas City is special because we have gems like Loose Park, Swope Park, and so on, which by themselves don’t quite offer the experience of Central Park, but when connected mentally as part of a system, a city-encompassing unit… well, that’s special.

Kansas Citians are also impressed by old things. (To be clear, we are not good at preserving them – and maybe it’s the resulting relative lack of historic structures that causes us to be taken when we do discover that some structure dates back to the early 1900’s.) The Parks and Boulevards System is an old thing. This plays into the allure of the legend.

But do Kansas Citians really understand the system? Myths, after all, are used to explain the poorly understood – do we know the facts?

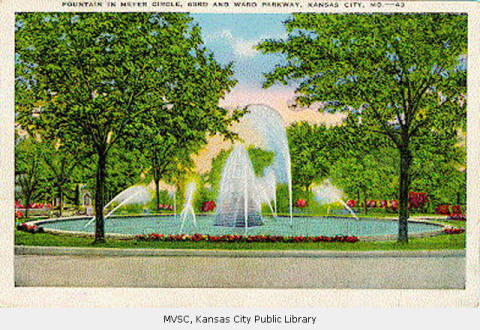

If you were to ask residents, “What is the Parks and Boulevards System?” most would probably answer with the better-used parts of the system: Ward Parkway, Gillham Park, Paseo, Swope Park. There will be confusion: “Hold on, is Mill Creek Park a part of it? What about Broadway – it’s a boulevard, technically? And are there parks or boulevards north of the river…?” (The answers, by the way, are yes to all.)

They might just list off all the parks and boulevards they can think of – which would almost, but not quite, be correct.

Some people – long-time residents, more likely – might be able to add a bit of historical context, having possible read the small collection of written work on our fabled system. (Remember, we like old things. And we have a good public library system.)

Others, meanwhile, would describe the Parks and Boulevards as a historical artifact – as dead, archaeological, in the past. Which is too bad.

The point is, Kansas Citians, myself included, really don’t understand one of the most distinctive features of the city’s physical environment. Which is too bad.

Reality

So what are the facts, and what’s just myth?

A lot of it’s true, actually.

First of all, the Parks and Boulevards System is indeed old. It dates back to the 1890’s, when KC was about 40 years old and its city limits extended to just 47th Street.

And Kansas City’s Parks and Boulevards System is, in fact, pretty special – there’s some truth to this part of the legend. It was designed by a German-American landscape architect/planner, George Kessler, who would go on to become a leading name in planning and would significantly shape at least a dozen other cities with similar plans. His designs for Kansas City, though, were maybe most significant and most distinctive of all his work.

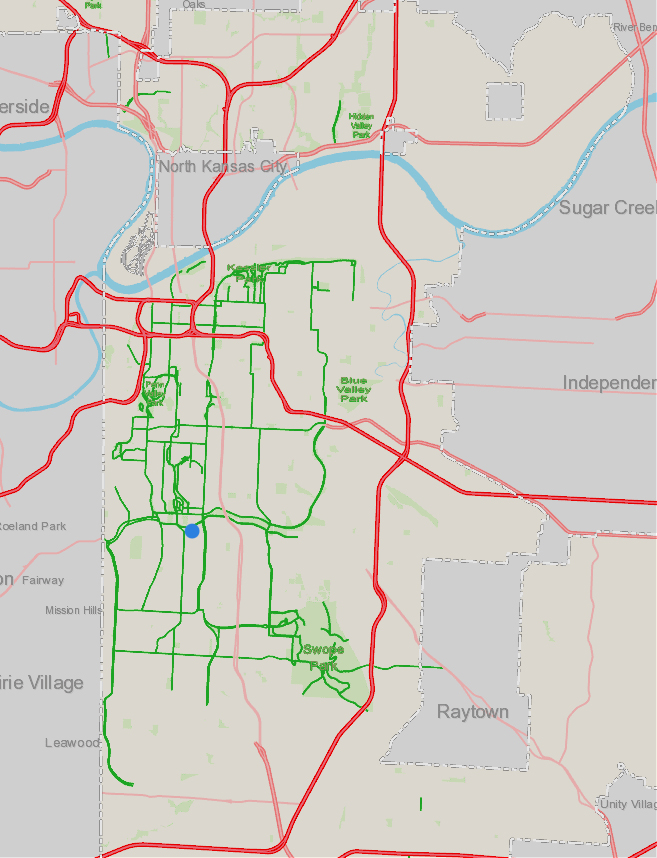

The Parks and Boulevards system, meanwhile, isn’t just a historical relic. In fact, the system is probably at its most extensive ever, especially with new parts of the system being added to the growing Northland. In the map below, the green is elements of the today’s system – which today include parks and boulevards, as well as parkways and roads, such as Ward Parkway and Rockhill Rd, that have been weaved into the system despite not being designated on maps as “boulevards.”

The extensiveness apparent in the map below shows that Kansas Citians are pretty much guaranteed, as long as they leave the house, to experience some part of the system on a daily basis. In fact, I can’t image a commute through the city (excluding those on highways) that involve at least crossing some boulevard or passing a park.

So in addition to still being in existence, Kansas City’s Parks and Boulevards System is also very much a part of our lives.

But are we aware of that, as we take a drive through town? And that leads to a bigger question: I’ve said that the P&B system is at its greatest physical extent – but can we really say unequivocally that it’s at its height in a cultural sense? Do Kansas Citians embrace and (consciously) engage with their mythical Parks and Boulevards?

Alive and Well?

So, the system is alive – at least in the sense it continues to be maintained and expanded, and ostensibly, used. Whether it’s “alive and well,” is debatable, though.

By saying locals use the Parks and Boulevards, what we’re really saying is that people use the Boulevards, and not so much the parks. Sure during certain times of day, Loose and Mill Creek Parks get traffic. (Both are avoided after dark, despite being very centrally located, due to almost zero lighting.) People go to Swope for the zoo and Starlight Theatre. Maybe some disc golf.

The city’s parks are by no means unused; but at the same time, for the thousands of acres of parks that exist and that are maintained (which implies that somebody expects them to be used), KC’s parks seem to receive a smattering of traffic. (And remember, these aren’t exactly my first impressions – I’ve noticed this for about two decades living here.)

Brush Creek and Parks

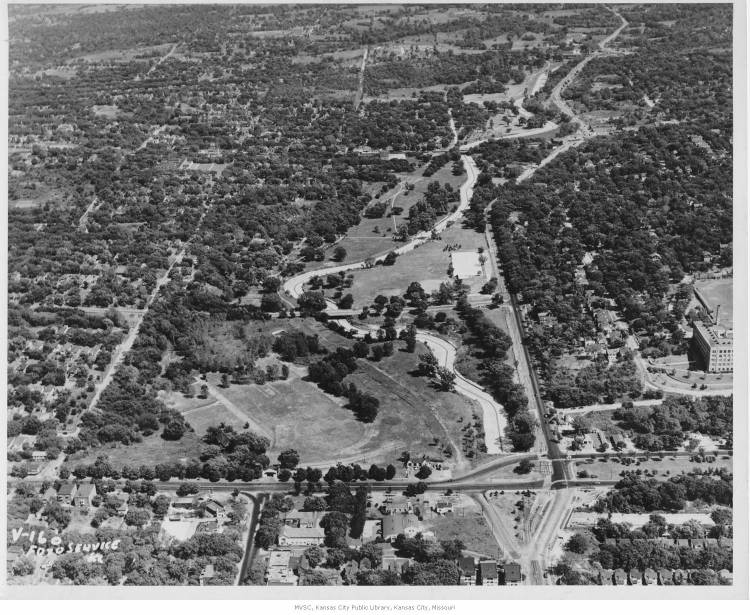

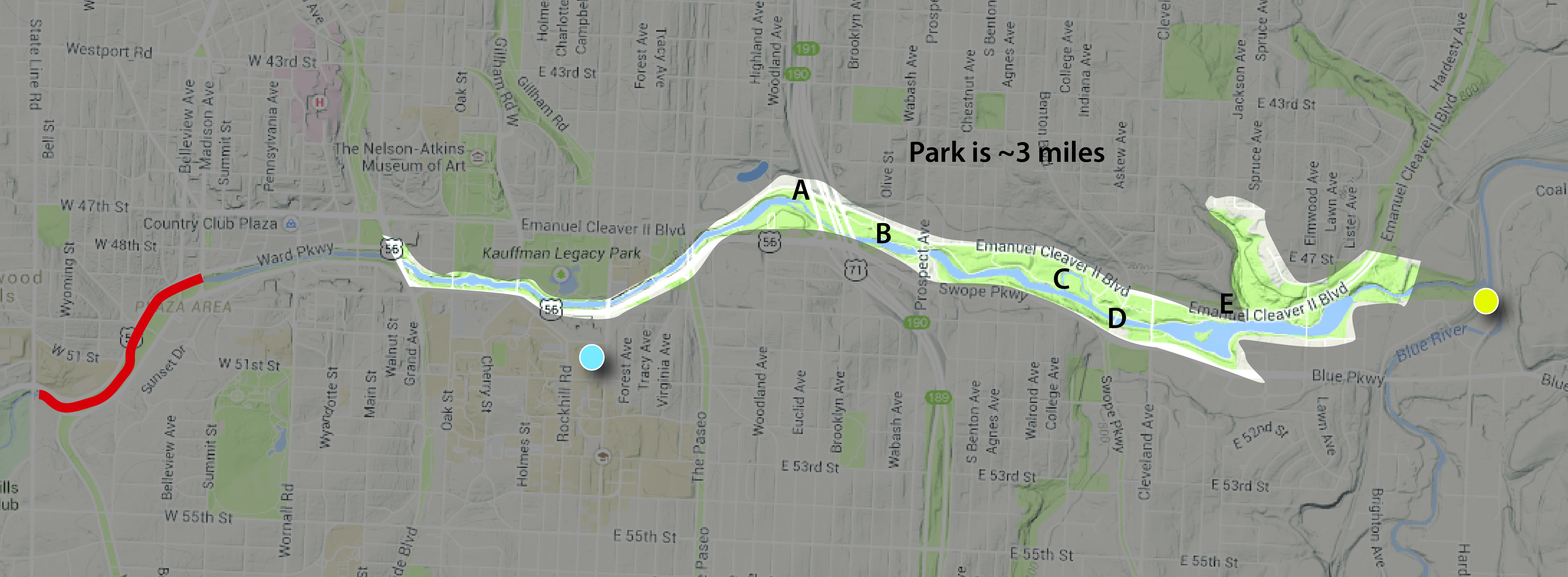

Take Brush Creek Park – or as the city’s local Parks and Rec department calls it, “Brush Creek Greenway Park”. Anyway, it follows the flow of Brush Creek from Brookside Boulevard in the west to almost where the creek meets the Blue River (the “Big” one).

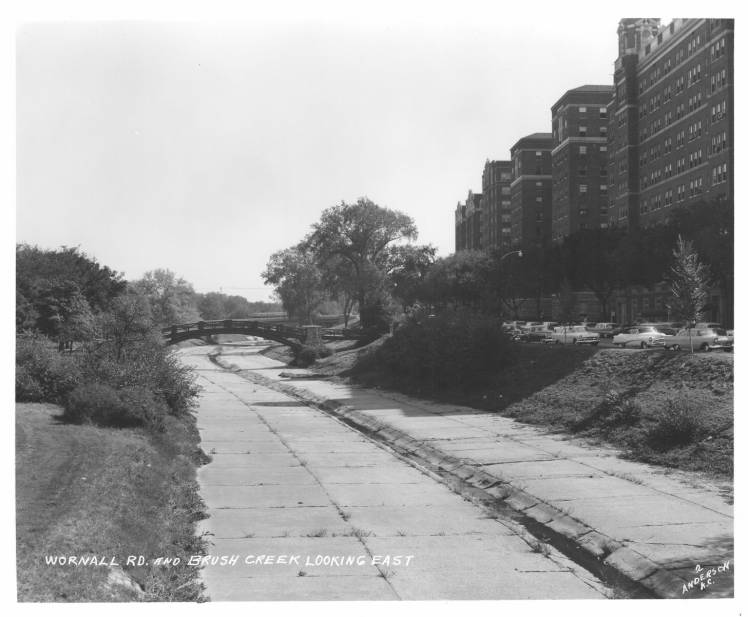

For non-natives of KC, let me just say this park is an incredible improvement over what used to be there. Transcendental. Since the days of boss Pendergast in the 1930’s, Brush Creek had been covered in concrete — with only a tiny rivulet of water in the middle visible — in an effort to control flooding.

The whole length of it.

This is what that looked like going through the Plaza in the 1970’s, when the so-called flood-control solution failed, actually exacerbating floods that killed a few people nearby:

And to underscore how much creek the concrete covered, here’s a photo of the covered creek, looking east from 47th and Paseo, about a mile east of the above photo:

It’s thought that those deaths got the gears of government grinding, and a revamp of the creek, directed by the US Army Corps of Engineers, was soon drawn up, and it began to be implemented in the ‘80s. Concrete was employed again, but this time it was used to build cascades, paths, and new bridges along the now “daylighted” creek (that’s the urban planning term for uncovering a body of water).

The Brush Creek Greenway Park encompasses, maybe, 9/10 of the improved creek. (Almost mile of the creek, between State Line Rd and the Plaza, is still covered in ‘30s concrete. It’s in red on the map. There’s another part of the creek through the Plaza that is not a part of the park.) Considering that, it’s a big park – about 3 miles long. And within those 3 miles is about 250 acres of open space – “park.” That’s a little misleading, too, because the Greenway Park runs through several other substantial parks – such as Theis Park – that aren’t counted towards that total.

Judged as a park – separate from its context – Brush Creek Greenway Park is a great park. You get basically three miles of uninterrupted trail along a decently scenic (ignoring the odd swirl of garbage) creek. There’s a lot of open space, some nice landscaping, waterfalls, fountains, and benches. Some decent views, too.

B- Plenty of visiting geese enjoy the park and views of the scenic, much-improved Brush Creek.

D – See? Very picturesque. This is the Benton Blvd. bridge.

E – And there are plenty of benches, lighting. Any people, though?

But what else is the park?

It’s empty.

The other day I took a bike ride from Katz Hall (the blue dot on the map) to the end of the park, where the trail also ends. It was a 2.86-mile ride on which I basically saw all 250 acres of the park.

That afternoon, I saw five people in the park – and one was a city worker picking up trash, while another was a homeless man who appeared to be living under the Cleveland Ave bridge. So, really, there were two people using the park for recreational purposes. I rode basically the whole length of the park – out and back – and saw three park users. It was a very nice day – about 60 degrees in late January – and it was rush hour, when parks often start to get filled with people exercising/relaxing after work and kids playing after school.

Two hundred fifty acres and the recent target of, surely, tens of millions of dollars of improvements was being used by three people.

Is this representative of all Kansas City parks? No. But a lot of them, yes. Based on what we’ve recently observed, touring parks on the east and northeast sides of Kansas City, yes. Based on what I’ve observed of various parts of the Parks and Boulevards system over 20 years – even on nice days – definitely, yes.

Paseo and Boulevards

What about boulevards, though? I’ve already admitted these are well used, right? Sure. But does just driving through count as fully, consciously partaking in them? What if saying you’ve used the Paseo by driving down it was similar to saying you’ve been to the Grand Canyon because you’ve flown over it?

On one hand that seems extreme, because by driving down any boulevard, you’re obviously using it. And you’re probably enjoying the scenic view its trees and plantings offer. On the other hand, there’ s a lot more to a lot of these boulevards than most of realize — experiences most of us never have because we tend to fly through the Parks and Boulevards. Example? Paseo, near downtown.

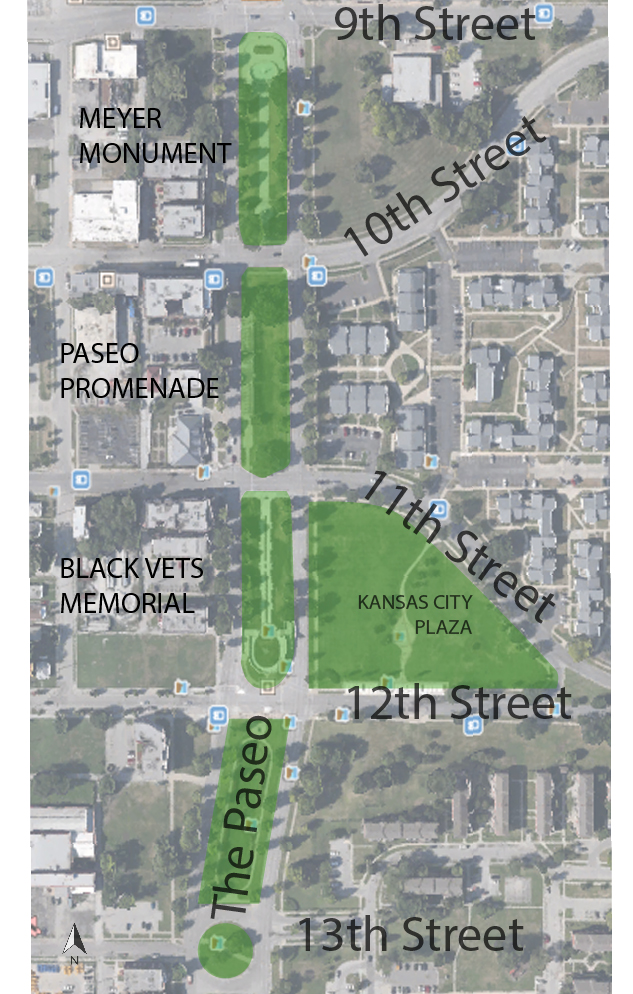

Paseo, for a good deal of of length, is more than just a tree-lined street. For several miles it has a substantial median, which works as park. On a stretch of the Paseo between 9th and 12th streets are some of the most attractive elements of the Parks and Boulevards system.

Exhibit A: The Paseo Pergola, located between 10th and 11th street.

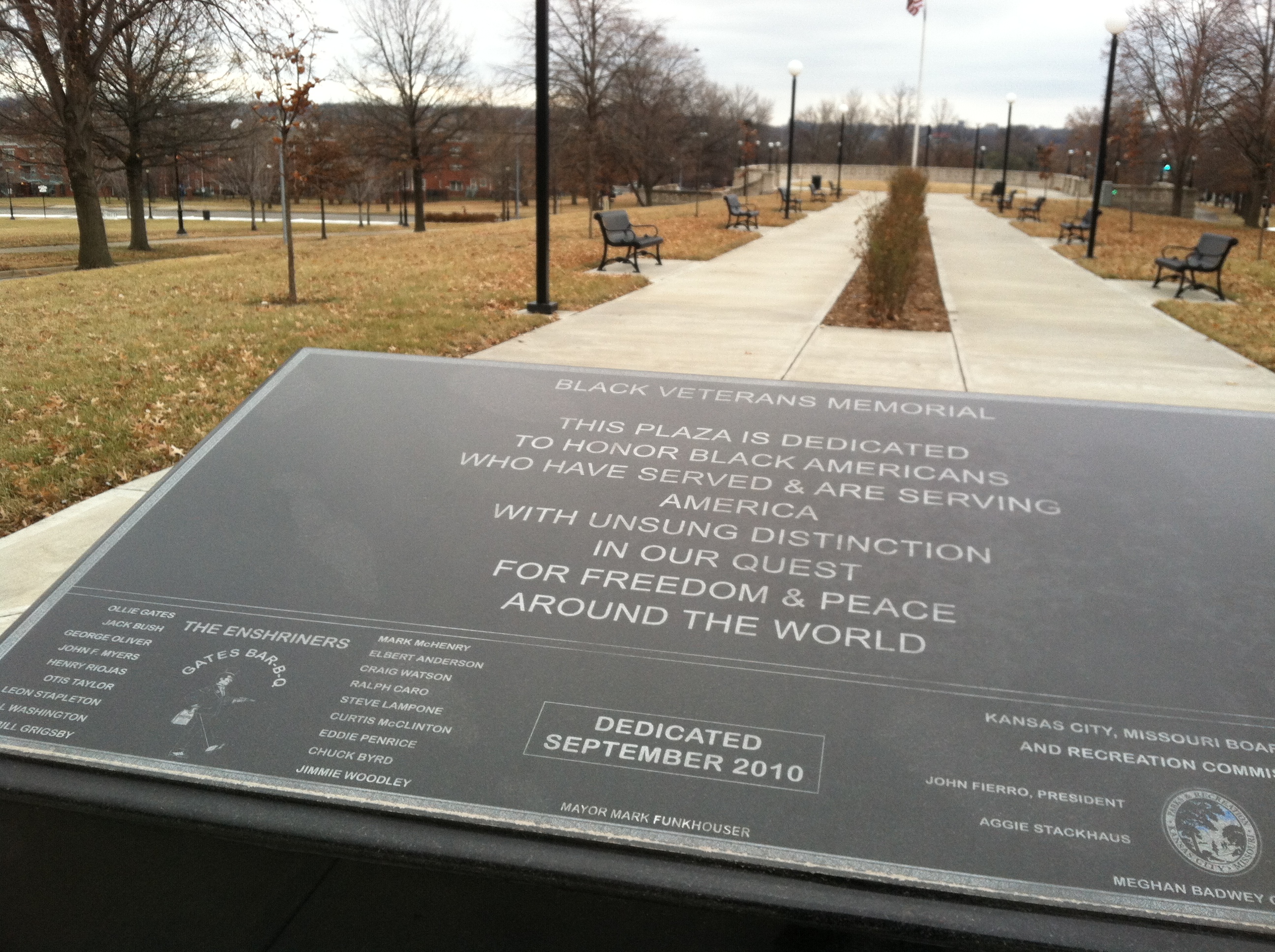

Exhibit B: The Black Veterans’ Memorial

Exhibit C: August Meyer (co-designer of the Parks and Boulevards system) Monument

In all, this three-block segment of the eight-mile Paseo is one of the most attractive, pedestrian-friendly, even “urban” spaces in the city.

And yet, no users were present — and I’ve rarely seen anyone there on sunny, warmer days either. There were plenty of people driving down the Paseo, but no one stopped to enter this park-like space.

Look around, though, and you might have the answer as to why no one was there: the urban fabric is in tatters. Some of photos above show apartment buildings — these once lined the entire street for about a mile. Now, they have mostly been demolished, replaced occasionally by industrial lots, incongrous and gated public housing, or just left vacant. There are no activity centers nearby, so hardly anyone’s walking along the street to begin with — those driving by are not stopping. (It’s really no different on Ward Parkway, which runs through a much “nicer” neighborhood — even there, there are no centers nearby, and people just drive by, not enjoying the amenities in the median.)

The same is the case around the Brush Creek Greenway Park. Here, though, there are mostly intact neighborhoods on both sides of the park, and attractive parkways/boulevards on either side. And yet, still no centers/destinations, other than the park itself. Plenty of people are driving by; no one’s stopping.

Going Forward

And that might point to the problem. We build new parks and beautify our old ones without giving thought to what really made them so great, what made them “work.”

The Parks and Boulevards were designed for a time when people took scenic leisure drives en masse. We don’t do that anymore. We drive to commute.

The Parks and Boulevards were designed for a time and when Kansas City had much stronger neighborhoods with well defined activity centers. We don’t quite have that anymore.

To the extent the Parks and Boulevards system was designed as an ornamental variation of an otherwise strictly functional road, it works. As a place where people relax, play, or gather, it mostly fails.

The system used to work — as you’ll see if you follow this blog throughout the semester.

But today, to say the Parks and Boulevards system works might be like saying a tree with half its limbs dead or dying is alive.

That’s the depressing part — taking stock of the the faded glory of one our city’s most distinctive, fabulous features

The exciting part is bringing back the glory, putting the epic back into the “myth.”

Stay tuned.