For many, the holiday season is a time of family, good food, and gift-giving. During wartime, however, this time of year can be rough for families separated from loved ones serving overseas. I heard just the other day that many troops overseas get so excited to receive any word from home or even better, a care package. Thanks to technology, communication is much easier as we don’t have to rely solely on snail-mail. Could you imagine how useful Skype or instant messaging would have been back in World War II?

For many, the holiday season is a time of family, good food, and gift-giving. During wartime, however, this time of year can be rough for families separated from loved ones serving overseas. I heard just the other day that many troops overseas get so excited to receive any word from home or even better, a care package. Thanks to technology, communication is much easier as we don’t have to rely solely on snail-mail. Could you imagine how useful Skype or instant messaging would have been back in World War II?

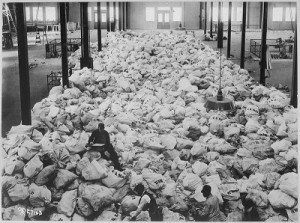

Inevitably, snail mail was the only option for them, but they made the most of it. According to a 1943 interview (available by request) with Kansas City postmaster, Alexander W. Graham, millions and billions of people send out Christmas cards, letters, and packages every year, including those serving in other countries. This interview served mainly to inform Kansas City listeners about cut-off dates for Christmas mailings. As an example of these deadlines, Postmaster Graham noted that the cut-off to send Christmas mail to somewhere as far as Australia was mid-September for Army and Navy personnel. Talk about doing some early Christmas shopping!

Since that time, shipping nationwide has gotten faster. I looked on the USPS 2011 mailing deadlines for nationwide shipping deadlines and found that a package can reach its domestic destination within five days. According to postmaster Graham, this deadline, which was subject to change based on how far across the country it would travel, was December 10th. Oh, how spoiled we are, that we have the luxury of Fed-Ex and UPS overnight shipping!

This interview had a specific purpose: to alleviate the shipping issues that the postal service frequently dealt with every holiday season. I think the funniest quote from the interview was the last comment on the subject. The KMBC interviewer asked Postmaster Graham if he had any other suggestions for listeners. His responded with the following: “…a postman is not allowed to loiter on his route, and if Mr. and Mrs. Average Citizen would […] indicate the zone delivery district number on the cards and packages they mail, they will do far more to relieve the postal employees of their Christmas headache than offering them a cup of hot chocolate.” Apparently, mailmen of that time were getting sick of drinking hot chocolate. So when you mail out your Christmas cards and gifts this holiday season, think of Postmaster Graham’s wise words, and don’t forget our troops overseas!

Gabby Tuttle, KMBC Project staff/Liberal Arts (BA) student