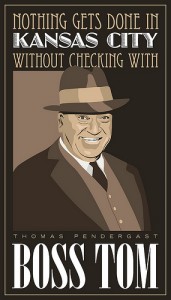

Not long ago, while working through an agglomeration of municipal election coverage that citizens of Kansas City would have heard over local airwaves during the early 1940s, we came across a rather unusual political broadcast pertaining to the Kansas City mayoral election of 1942. In what initially seemed to herald yet another fifteen minutes of electioneering characterized by the formulaic repetition of cliched political phrases and the championing of hackneyed party platforms, as would have been consistent with other broadcasts we had theretofore encountered, the KMBC host introduced a Captain Raymond G. Barnett, who would speak on behalf of the Citizens’ Campaign Committee (an allegedly non-partisan, anti-corruption organization). In what followed, however, Mr. Barnett surprised us all. To call Mr. Barnett’s speech an impassioned plea to the Kansas City electorate would do it little justice. One might more appropriately label Mr. Barnett’s speech, at its climax, a vehement jeremiad of near-Shakespearean caliber, in which he condemned the corruption that had plagued Kansas City politics in recent decades and besought the local citizenry to recognize that machine politics were no mere specter of bygone years. What upon first hearing elicited amused laughter from all of us for its sheer eccentricity, however, must not be treated as an inexplicable oratorical aberration purely attributable to colorful idiosyncrasies of the speaker. Out of respect for this fragment of the past, which would likely but for the Arthur B. Church collection have been lost in the airwaves of history, we must endeavor to distill some concrete meaning from Mr. Barnett’s speech in order to discern its historical significance. To listen to an excerpt from the speech, click on the audio player below. [audio:http://info.umkc.edu/specialcollections/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/2011-11-09_RaymondBarnett_Church_kmbc-247.mp3|titles=Raymond G. Barnett Speech]

Not long ago, while working through an agglomeration of municipal election coverage that citizens of Kansas City would have heard over local airwaves during the early 1940s, we came across a rather unusual political broadcast pertaining to the Kansas City mayoral election of 1942. In what initially seemed to herald yet another fifteen minutes of electioneering characterized by the formulaic repetition of cliched political phrases and the championing of hackneyed party platforms, as would have been consistent with other broadcasts we had theretofore encountered, the KMBC host introduced a Captain Raymond G. Barnett, who would speak on behalf of the Citizens’ Campaign Committee (an allegedly non-partisan, anti-corruption organization). In what followed, however, Mr. Barnett surprised us all. To call Mr. Barnett’s speech an impassioned plea to the Kansas City electorate would do it little justice. One might more appropriately label Mr. Barnett’s speech, at its climax, a vehement jeremiad of near-Shakespearean caliber, in which he condemned the corruption that had plagued Kansas City politics in recent decades and besought the local citizenry to recognize that machine politics were no mere specter of bygone years. What upon first hearing elicited amused laughter from all of us for its sheer eccentricity, however, must not be treated as an inexplicable oratorical aberration purely attributable to colorful idiosyncrasies of the speaker. Out of respect for this fragment of the past, which would likely but for the Arthur B. Church collection have been lost in the airwaves of history, we must endeavor to distill some concrete meaning from Mr. Barnett’s speech in order to discern its historical significance. To listen to an excerpt from the speech, click on the audio player below. [audio:http://info.umkc.edu/specialcollections/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/2011-11-09_RaymondBarnett_Church_kmbc-247.mp3|titles=Raymond G. Barnett Speech]

Born in 1882, Raymond G. Barnett was a western Illinois native who spent the later part of his youth in Kansas City, where he completed his high school education. He matriculated at the University of Missouri and later at Stanford University, where he earned both his Bachelor of Arts and law degrees. He later returned to Kansas City where, aside from a brief and unsuccessful candidacy for local office, he would serve as a legal professional for much of the remainder of his life. Notably, Mr. Barnett’s otherwise local lifestyle was interrupted in 1917 following his induction into the Army officer corps upon the United States’ entrance into the First World War, after which he was sent to serve in France. After the War, Captain Barnett returned to Kansas City where he would continue his professional career and remain politically active in support of the Republican Party into the late years of his life.

In view of Mr. Barnett’s personal background and the political context in which his speech aired, the visceral conviction that shone through his radio tirade becomes much more comprehensible. Having witnessed many horrors in the First World War suffered in what he certainly saw as the service of freedom, Captain Barnett must have been incensed by the corrupt political dynamics that emerged in his adopted home of Kansas City in the 1920s and 1930s. The very undemocratic nature of Tom Pendergast’s machine politics was clearly an affront to his sense of the democratic values that America represented, especially as his speech aired during the early months of American involvement in World War II. This comes through rather clearly in his insistence that Kansas City demonstrate that it was “keeping faith with the heroes and martyrs of the past who gave us freedom’s priceless heritage,” as well as his colorful, though unpleasant allusion to the human sacrifice unfolding on the battlefields at the time of his speech. A man of roughly 60 years of age at the time, Captain Barnett likely crafted both the prose and the delivery of his speech with the hope of cementing what he viewed as the true and hard-won legacy of his generation and that not yet secured by the young men then fighting overseas. Sidelined from active duty in the second Great War by the decrepitude of age, Captain Barnett likely saw himself as a soldier fighting for the cause of freedom on the home front.

Dustin Stalnaker, KMBC Project staff/History (MA) student

To access the complete recording, you may request the recording from the Marr Sound Archives.