Countless times each day we are bombarded by visual rhetoric, the use of images to influence or persuade an audience. The persuasive element of visual rhetoric lies in its ability to instantly connect with our emotional mind before the rational part of the brain is signaled. Using an example of World War II propaganda from UMKC LaBudde Special Collections I will demonstrate the mechanics and effectiveness of visual rhetoric while expanding understanding of how images influence people.

Countless times each day we are bombarded by visual rhetoric, the use of images to influence or persuade an audience. The persuasive element of visual rhetoric lies in its ability to instantly connect with our emotional mind before the rational part of the brain is signaled. Using an example of World War II propaganda from UMKC LaBudde Special Collections I will demonstrate the mechanics and effectiveness of visual rhetoric while expanding understanding of how images influence people.

Visual rhetoric techniques make use of the appeal of pathos, a form of persuasion appealing to an individual’s emotions – rather than their rational mind – therefore having greater persuasive influence (“The Forest of Rhetoric”1). Although it might seem hard to believe that humans can be influenced subconsciously, it can be explained by the observations of neurobiology researchers Joseph LeDoux and Antonio Damasio. They suggest that when the eye observes a visual image, a signal is sent to the cortex, the part of the brain that houses rational thought (Damasio). But before the sensory signal is sent there, another signal is first sent to the amygdala, the part of the brain that processes emotions and memory (LeDoux). Thus, the amygdala creates an emotional response before the mind can fully perceive an image. This circumvention of reason and provocation of emotional response is the goal of visual rhetoric elicit.

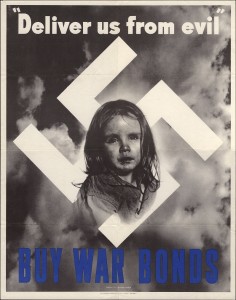

In the next section I will analyze an example of World War II propaganda and explain the techniques used in the image. Upon looking at the poster, “Deliver us from evil,”2 emotions of dread and fear are conveyed to the viewer. There is also a strong desire to help the child in the center and a loathing felt towards the enemy. But why?

The first aspect that conveys these emotions is the color scheme. The black and white image expresses a sense of negativity and despair because there are no bright colors that normally illustrate happy moods. Even the blue font reading “Buy War Bonds” is muted and doesn’t stand out, compelling the viewer to focus on the girl rather than the intended response of promoting war bond purchasing in a more natural, less contrived way. The quote at the top of the poster, “Deliver us from evil,” is an excerpt from the Lord’s Prayer, something that most onlookers would be able to recognize because at the time the majority of Americans were Christians. This quote emphasizes a sense of desperation because prayers are commonly associated with a time of great need and obstacles to be overcome. It also acts as a call to arms for the American population to rise up and fight off the “evil” (Deliver us from evil). The word “evil” obviously refers to Nazi Germany, symbolized by the swastika in the center of the poster, surrounding a frightened girl. The poster also associates the word “us” with the young girl in the center, asking the viewer to save her and girls like her. Looking at the child communicates a feeling of empathy and suffering because her hair is disheveled, her eyes are tearing up, and her clothing is worn and dirty. The use of a young girl is also a key factor in this example of visual persuasion intended to demonize the enemy. The girl is a symbol of innocence and purity that, in the context of the image, is in danger of being corrupted and harmed by the Nazi government. This imparts a sense of protection on the viewer to defend the child, and creates a negative impression of the German government. Thus, it becomes assumed that the enemy is wrong and therefore we, Americans, are in the right. All of these factors are linked with the hardship and pain which the viewer is able to identify easily.

Returning to the connection between the word “evil” and Nazi Germany, this link is made for two reasons: the matching colors of the word and swastika and the placement of the symbol surrounding the little girl. In the poster, white is the brightest color and since both the word “evil” and the swastika are both the same shade of white the eye recognizes this and the mind instantly associates one with the other in the context of the image. As for the position of the swastika, it looks as if it is trapping the little girl and is therefore responsible for the hardship and agony that the girl is experiencing.

The combined effects of associating the word “evil” from the Lord’s Prayer with the swastika causes the viewer to associate Germany and Nazis with negative images. This leads civilians to dislike and even hate the Allied enemies and subsequently generate a sense of duty to support for the war effort with the hope that children similar to the one in the poster are protected. Underlying all of these emotions is the subtle message of the poster “Buy War Bonds” (Deliver us from evil). This is intended to be the overall reaction to viewing the propaganda, and although it is not overly emphasized, there is no room left for questioning the message or an alternative option. It’s a firm, declarative statement with the unsaid “or else” that implies that the child in the poster will suffer if not followed.

Visual rhetoric is a persistent influence on our lives every day and is a powerful force in shaping our biases and perceptions. Being able to recognize patterns of visual persuasion and decipher how certain themes evoke certain responses will enable scholars to be more effective at communicating with the general public. Increasing public understanding of visual rhetoric will not only increase the awareness of the many influences people encounter daily. It will also lead to more logical and unbiased decisions made due to people recognizing the media’s and interest groups propaganda efforts and therefore rationalizing the issue instead of letting emotion control one’s actions.

Contributed by Alex Poppen (for English H225)

Sources:

1“The Forest of Rhetoric.” Silva Rhetoricae. Web. 23 Oct. 2012.

2“Deliver us from evil.” WWII Poster Collection. Dr. Kenneth J. LaBudde Department of Special Collections, Miller Nichols Library, University of Missouri–Kansas City, Kansas City, MO.

Like this:

Like Loading...

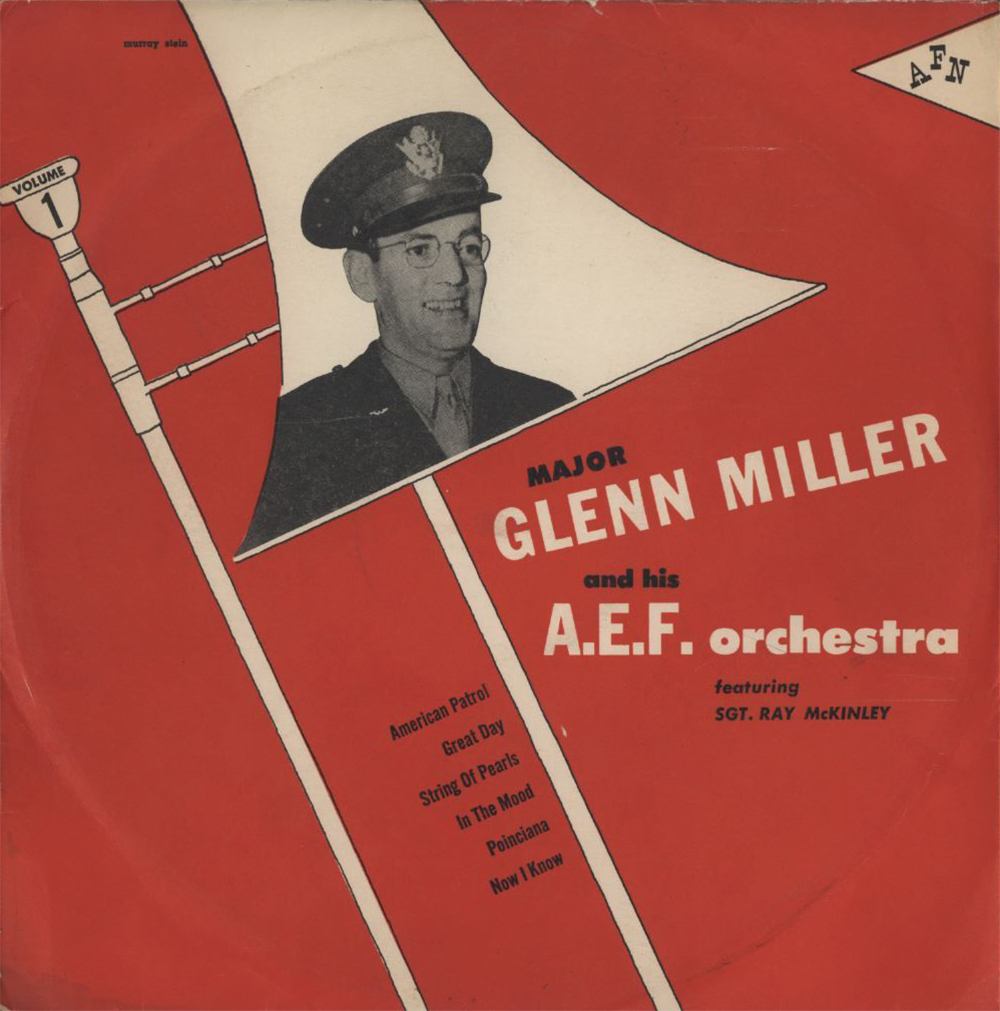

The Marr Sound Archives holds two albums from the uncommon broadcast recordings of Major Glenn Miller and the American Band of the Allied Expeditionary Forces. These two albums are compilations of recordings over the American Broadcasting Station in Europe, EMI Studio, St. John’s Wood, Abbey Road, London England and are simply titled “Major Glenn Miller and the A.E.F. Orchestra.”

The Marr Sound Archives holds two albums from the uncommon broadcast recordings of Major Glenn Miller and the American Band of the Allied Expeditionary Forces. These two albums are compilations of recordings over the American Broadcasting Station in Europe, EMI Studio, St. John’s Wood, Abbey Road, London England and are simply titled “Major Glenn Miller and the A.E.F. Orchestra.”