Lucile Bluford was an editor, and eventually manager of the black weekly newspaper, The Kansas City Call. Through the paper she was able to bring attention to issues of segregation in Kansas City, and around the nation. An example in her long resume of encouraging change, Bluford encouraged the Community Committee for Social Action in their efforts protesting and effecting change with regards to downtown department store segregation. Bluford was also present at the Kansas City Riot in 1968, engaging with the story on the ground. Even though she argued that protesting should be more peaceful, she still managed to utilize The Call in her efforts to fight against the blatant displays of police brutality at the riot, as well as the police brutality on the everyday streets of the city.

Journalistic Activism: Lucile Bluford’s Fight for Civil Rights through The Kansas City Call

by Kristina Roberts Ellis

As the editor of the Kansas City Call, a prominent black weekly newspaper, Lucile Bluford did not consider her job an occupation, but a calling and a responsibility. She felt beholden to her African American community to expose racism and provide news pertinent to their lives. Bluford claimed that “every movement for the advancement of black citizens has been championed and fought for through its news pages, its banner headlines and through its editorial columns.” She encouraged the fight for equal rights and vehemently opposed discrimination against blacks in Kansas City and in the United States.

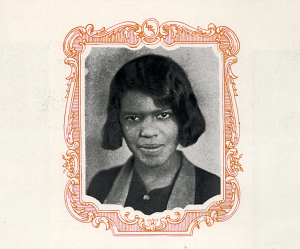

Born in 1911 into a middle class, black family in Salisbury, North Carolina, Lucille Harris Bluford lived there until the age of ten. She then moved to Kansas City where her father taught science at the all-black Lincoln High School. From early childhood, Bluford encountered the realities of Jim Crow segregation. In elementary school, she walked two miles to and from school, passing an all-white elementary school that was only two blocks from her home along the way. Bluford felt “it was silly” to have to walk so far when there was a white elementary school nearby, but explained that “segregation was more or less accepted by everybody in those days, it just was.” This placid acceptance of racial norms did not continue throughout her life.

Bluford joined the NAACP as a teenager. Over her summer breaks, she worked at The Call, filling in for staff members on vacation. Bluford attended Lincoln High School where she first became interested in journalism and worked on the school newspaper, the Lincolnite. In a pointed 1926 Lincolnite article entitled, “Better Schools,” Bluford addressed the glaring differences in white and black educational facilities. She railed against Lincoln’s inadequate physical structure and criticized the empty promise of a new facility. In her concluding paragraph, Bluford expressed frustration with the delay in a new school and hoped it did not result from the opinion that “Negro citizens do not deserve a new school.” When Bluford graduated from high school as valedictorian in 1928, she did so with an awareness of racial discrimination and a developing drive to do something about it.

Bluford’s activist leanings increased in her late teens and early twenties. She attended the University of Kansas from 1928-1932 as the sole black student in the journalism program. Bluford majored in journalism and wrote for the university’s student newspaper, but she continued spending summers working at The Call.

After graduating from Kansas in 1932, Bluford moved to Atlanta and worked a short time for the Atlanta Daily World, the South’s largest black newspaper. Feeling homesick, irritated by segregated streetcars, and disliking the oppressive southern heat, Bluford moved back to Kansas City only months later in the fall of 1932. The Call did not have any job openings at the time, so Bluford began working for the Kansas City American, another black weekly newspaper and The Call’s competitor. Bluford’s tenure at the American was also short. She wanted to return to The Call and applied for a position there as soon as a position became available. Bluford respected and identified with The Call’s mission.

Part of “The Call Platform,” included in every issue, reads “Hating no man. Fearing no man. The Call strives to help every man in the firm belief that all are hurt as long as anyone is held back.” Bluford first started working as a copy editor, but she quickly moved up to cub reporter, desk editor, city editor, and, in 1938, managing editor.

As managing editor of The Call from 1938-1955, Bluford decided which topics received attention, assigned staff members to stories, and determined the paper’s layout. Bluford became editor in chief of The Call after Chester Franklin died in 1955. Not much changed in terms of her workload since she had already taken over most editorial responsibilities nearly three years beforehand. In 1983, when Franklin’s wife Ada passed away, Bluford became owner and publisher of the newspaper. As editor, publisher, and eventual owner of the newspaper, Bluford was an anomaly for her time.

Bluford’s position as editor of The Call was unique. While scholars note that “black women journalists have had to contend with twin barriers: discrimination based on race as well as gender,” Bluford had a different experience. Despite her non-traditional role, she said she never had any “trouble” as editor, asserting that there had “never been any discrimination against women at The Call” and she “never felt pressure for being a woman.” During a time when the majority of female civil rights activists and journalists worked behind the scenes and took a back seat to male leaders, Bluford called the shots and her ideas received front-page attention.

The Call was not simply a news outlet but also an agent of change. The 1950s and 1960s produced a host of opportunities in Kansas City to fight for change. Still The Call paid equal attention to national integration efforts, giving gave the 1954 Brown v Board of Education decision significant coverage. Bluford devoted an entire issue to the Brown decision, referring to it as the “climax …of what we’d been working toward.” In an editorial, she called the unanimous decision a “sweeping” and “decisive” “knock out” and “by far the greatest victory which Negroes have won in the 45 years they have fought for first-class American citizenship.” Bluford repeatedly extolled the virtues and positive implications of the Brown decision.

By the mid-1950s, most public facilities in Kansas City had been desegregated. Bluford had extensive experience with trying to integrate eating establishments. According to her, “Kansas City led the way” and was the “first to perform sit-ins.” In the early 1950s, she and her white friend Virginia Oldham visited restaurants together to “get people accustomed to seeing black and white people together” and to show that when they ate together “nothing was going to happen.” They “surveyed” different restaurants each week. In one instance, they tried the Forum Cafeteria where diners walked through a buffet line. Bluford, expecting to be pinned in by white customers, got in line with Oldham. The Forum employees did not ask her to leave, but they refused to serve her. Much to their chagrin, Oldham simply purchased enough food for both of them. Bluford “[got] a kick out of” testing various Kansas City restaurants’ segregationist policies. Devoted to chipping away at the racial status-quo, Bluford used The Call to aid in a similar confrontation.

Downtown department stores desegregated in the early 1950s, welcoming African Americans as shoppers and consumers, but store managers and the downtown chamber of commerce prohibited blacks from eating in the stores’ restaurants and cafes. In an effort to capitalize on integration success elsewhere in Kansas City, a local black social club, the Twin Citians, “spearhead[ed] the effort to integrate the city’s downtown department store restaurants,” one scholar wrote. Bluford attended a Twin Citians meeting and suggested that they “reach out to other black clubs and organizations for support.” The club followed Bluford’s advice, gathering other organizations to its cause, establishing the Community Committee for Social Action (CCSA), and planning the attack. In her weekly editorial, Bluford announced the CCSA’s plans and lauded their effort to “right a wrong.”

After seven weeks of declining sales, store managers agreed to negotiate with the CCSA. The committee agreed to “suspend picketing” for a short time, but revealed its plan for a mass march on February 27, 1959. Several store managers, hoping to avoid additional negative attention and revenue loss, agreed to open their cafeterias and restaurants to African Americans, effective the same day that CCSA planned to march with 1,000-2,000 participants.

After the stores agreed to “participate in integration,” Bluford referred to the outcome as a “grand and glorious victory” and declared that “right and justice won out.” As an optimist, Bluford relished these civil rights successes. A decade later, however, Bluford’s ability to remain positive would be tested.

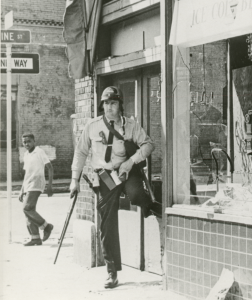

In the mid to late 1960s, Kansas City race relations boiled under the surface. Anger and frustration came to a head following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination on April 4, 1968. Five days later, the nation mourned as he was laid to rest in Atlanta. Many school districts across the country, including the Kansas City, Kansas school district dismissed students from school, but the Kansas City, Missouri school district did not. This decision created resentment in the African American community. In response, Kansas City youths marched downtown to protest and tension escalated from there.

What started as a peaceful march at city hall erupted when someone from the crow supposedly threw a glass bottle at police. Kansas City police responded by firing tear gas into the crowd and then, according to Bluford, “everything erupted.” In response, “angry blacks proceeded to vandalize and burn white-owned businesses.” Meanwhile, police snipers and armed blacks exchanged gunfire. Bluford was away attending Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral in Atlanta, but on her return flight, the pilot announced rioting in Kansas City. Once back home, Bluford took to the barricaded streets to observe the rioting first-hand. Bluford “rushed to cover the violent confrontation,” becoming “part of the story” herself, witnessing the action from under a nearby car. After two days and two nights of pandemonium, 1,700 National Guardsmen joined 700 local police officers to quell the violence, looting, vandalism, and arson.

Bluford was a product of the NAACP, which supported a more conservative and gradual approach to civil rights. She regretted the violence and believed that, given his “legacy of non-violence,” King would have been “disappointed” by the rioting. She used The Call to “clearly establish” that “Negroes as a whole do not condone rioting” and made the point that “negroes suffer more than any other segment of the population during violent outbreaks.” While Bluford found the rioting discouraging, she was thoroughly appalled by what she, and many others, saw as police brutality.

In the weeks and months following the riot, The Call’s attention centered on the violence meted out by the Kansas City police department. The Call related the circumstances surrounding the deaths of six black citizens and the injuries sustained by at least fifty rioters. Clearly placing blame on police, an article explained that “civil rights leaders said…members of the police department themselves triggered the rioting by the unwise use of tear gas on a group of students…who were conducting a peaceful march from their schools to the City Hall in tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King.” In a rare departure from her editorial section at the back of the paper, Bluford authored a front-page article with her name affixed. She expressed concern writing that “the relationship between the Negro community and the Police department, already at the straining point, is now on the brink of breakage as a result of incidents involving police action during racial violence.” Bluford believed a “thorough, impartial and fair investigation [was] needed and wanted.” She had no intention of letting the issue become yesterday’s news.

Bluford referred to the chief of police by name and criticized the department’s delay in releasing a report from an internal probe. Bluford accused the police department of “minimiz[ing] and condon[ing] the acts of its officers” and of withholding information from the public. Police brutality continued to receive attention in The Call long after the riot ended and Bluford, yet again, became a voice for those who did not have a platform.

Bluford was often referred to as the “conscious of Kansas City.” She hoped to influence public opinion and bring awareness to the community through her writing, using her “journalistic skills to fight for social change.” She used her platform “to advocate and to campaign for justice, first-class citizenship, democracy and fairness.” Hoping someday to not have to fight so hard for so much, Bluford said her goal was to “work [myself] out of a job.” Using The Call as her “instrument of protest” for over seventy years, Lucile Bluford was one of the city’s most well-known, and respected civil rights activists.