Drew Shafer was an early activist for gay rights in Kansas City, primarily contributing to the movement in the 1960s. Shafer helped to organize the North American Committee of Homophile Organizations (NACHO) and he founded the Phoenix Magazine and Phoenix house, both efforts that supported gay men in their struggles to come out and to live openly as gay men.

Drew Shafer: Building Gay Identity in Kansas City and Beyond

by Kevin Scharlau

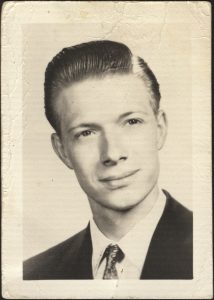

Drew Robert Shafer—born April 9, 1936—was out of the closet by the age of twenty-one. Shafer’s drive and passion for gay rights was unmatched in Kansas City in the 1960s, but it is hard to believe that he could have become the activist he was without the family life he enjoyed. During Shafer’s formative years, gay rights and Kansas City were incompatible terms and Shafer’s own sentiment places him as a reluctant activist. He once mentioned to Mickey Ray, his longtime partner, that he would rather open a bar or club in town and just have a good time. He hosted parties and served as the head of an inclusive social network. The parties only befuddled those who attempted to pin down what exactly made him organize, but Shafer grew into much more than a host or bar regular. He devoted his activism toward making life better for others who lacked the support system he had. By the mid-1960s, he started giving speeches on college campuses about gay rights.

Political rights for gays seemed impossible. It was not until 1966 that an organized group ventured to connect gay men and women in Kansas City through self-publishing, political meetings, and fellowship. Shafer’s Phoenix Society for Individual Freedom—Kansas City’s first gay rights organization and one of only sixteen such organizations nationwide at the time—was created to introduce men to one another and, perhaps more importantly, to homophile politics. The organization disseminated information that increased gay men and women’s political awareness.

Shafer’s organized activism began in 1966 with the National Planning Conference of Homophile Organizations (NPCHO) meeting in Kansas City. Supportive and involved from the beginning, Shafer’s mother attended with him under the pseudonym Estelle Graham. The meeting was the first of its kind nationally. The sixteen separate gay rights organizations spent two days in the State Hotel downtown discussing cooperation. They created the North American Committee of Homophile Organizations (NACHO) and agreed to nationalize their efforts.

The weekend of the conference, Shafer went on a local radio show to discuss why gay organizations in town were meeting. A precociously open man, Shafer told his manager at the Caterpillar Tractor Company plant he needed time off to speak on a radio show. “He was nearly fired…when he ‘came out’ to the listening public on the radio,” his partner remembered. The United Auto Workers Union managed to save his clerical job from an enraged manager. The experiences with local police and bigoted employers mirrored many in the gay community.

When asked at NPCHO what problems Phoenix would address, Shafer responded with one word: “Communication.” Shafer was still in the infant stages of forming his organization and likely did not know what role it would play, but this comment hints at his underlying sense that the community in Kansas City—and nationwide—needed to be brought together, to have an outlet where isolated men and women could come to grips with their shared identity and build a cohesive movement. The country was in the midst of what has since been labeled the Lavender Scare—a period of widespread discrimination against homosexuals characterized by McCarthyism and the wider Red Scare. Government at all levels actively sought to out and oust homosexuals within its ranks. In this atmosphere—and with no legal protections from such targeting—open lines of communication between homosexuals was unfathomable.

How could Shafer’s Phoenix Society, an organization consisting of no more than twenty members at its outset, bring the wider gay community together and invest them in homophile politics during an era when it was easier to stay hidden? By 1966, the homophile movement had a nearly fifteen-year track record of quality publishing—newsletters and magazines that were available for subscription but also stocked in friendly bookstores, gay bars, and other establishments. The homophile magazine was an outlet that provided a literary connection to the homosexual community. Whereas mainstream society portrayed homosexuals as deviants and pariahs, the revolutionary publications of various organizations in San Francisco and Los Angeles gave readers homosexual characters and issues to identify and sympathize with for the first time.

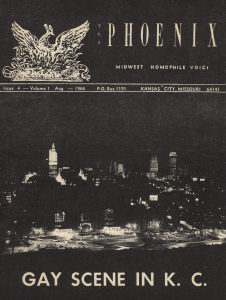

Shafer’s father, Robert began his career as a pressman for Sexton Printing. He later went on to serve in a similar role with Burd and Fletcher Company. His experience and, more importantly, his equipment allowed Phoenix Society to create a top tier publication in what would be the first of its kind in the Midwest. With his father’s help, Shafer began publishing The Phoenix: Homophile Voices of Kansas City in April 1966.

The magazine itself was a byproduct of Shafer’s direction, the skill of several writers and artists, and the grunt work of Phoenix members who wanted to help in any way possible. The magazine ran between sixteen and twenty-four pages per issue, with new editions released once a month. They had short stories, poems, art, editorials, and current events rundowns. They received letters to the editors from across the country, hinting at a wide distribution network through NACHO connections and subscriptions.

For the two years Shafer served as president of Phoenix, the first words any reader saw in The Phoenix were his. In the recurring segment called “The President’s Corner,” Shafer introduced the group, explained what it was working on, and defined the issues facing Kansas City’s gay community. In addition to Shafer’s words, readers could always expect to see stories from “Estelle Graham”—in reality, Phyllis Shafer, his mother. Phyllis’s writing provided a motherly support for the entire readership and her articles often read as advice columns. In one, titled “A Mother’s Viewpoint,” she provided advice to the families of potential readers on accepting and loving a homosexual child. “Homosexuals are wonderful human beings who are no different from heterosexuals except for often being unhappy, scared, frustrated people,” she wrote. “The best thing a homosexual’s family can do for him is to accept him as he is and to make it possible for him to quit living a double life.” Her writing and involvement in Shafer’s homophile organization demonstrates the kind of support that kept Shafer going.

Charles, an acquaintance of Drew’s, remembers Phyllis Shafer.

Before leaving the office of president to embark on a new chapter within Phoenix’s activism, Shafer wrote his last editorial in April 1968. He outlined what the group accomplished during its first two years and pointed the organization forward. Phoenix “had representatives on several radio and television programs, sent speakers to various colleges and universities, and established and maintained firm contacts with many clergymen in our area.” Shafer also highlighted Phoenix’s printing efforts that stretched beyond the magazine. “We have printed several informative pamphlets,” including ones on venereal disease prevention, religion, and homosexuals in the military, he explained. The pamphlet “Venereal Disease and Homosexuality” was of special import, seeking to reduce the effect of sexually transmitted diseases within in the community and for its co-sponsor—Phoenix enlisted the cooperation of the Kansas City Public Health Department. The pamphlet provided contacts for sympathetic health care providers and tamped down fears of gay men who worried about publicly seeking help since it would risk exposing their homosexuality. Phoenix was two years old and its members had accomplished so much in bringing the community together, but Shafer’s editorial signaled that they were just getting started.

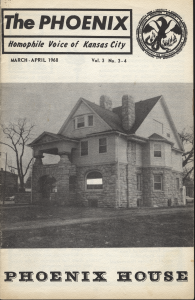

Shafer’s full imagination of what the Kansas City’s first gay organization could be came to fruition with his purchase of Phoenix House. Located in the Midtown neighborhood on Linwood Boulevard, Shafer envisioned a gay community center, an organizational headquarters, and a home all rolled into one. He lived on the third floor but the second floor served as a halfway house of sorts for gay men who had been kicked out by family after coming out. The massive home offered a lending library, replete with gay-centric literature and magazines, along with meeting rooms and an office for the president and secretary of Phoenix. The basement housed the advanced printing and mailing operation. On the first floor, Phoenix members regularly gathered in the living room, discussing initiatives and planning the magazine.

Whereas The Phoenix fit neatly into the pattern of what other homophile organizations were doing, Phoenix House marked Shafer’s unique vision. Shafer specifically did not run for the Phoenix Presidency in 1968 in order to work on Phoenix House, instead accepting the role of Secretary. In August 1966, NACHO had chosen Phoenix to serve as the national movement’s publishing clearinghouse when it met in San Francisco. Shafer admitted that accepting the role that early in Phoenix’s existence reflected “more zeal than commonsense.” Nonetheless, by mid-1967, the clearinghouse was up and running and, by 1968, Shafer’s role as secretary put him in charge of the process. Phoenix reprinted and distributed newsletters and press releases nationally, using the NACHO’s roster of addresses to reach a wider base. Around the time the clearinghouse effort ramped up, Shafer met Mickey Ray—the man who would be his partner for the rest of his life. He moved in with Shafer, jumped right into the clearinghouse work, and together they reprinted and mailed thousands of newsletters and press releases over the next two years.

Phoenix Society—along with the rest of the homophile community—gave birth to the Gay Liberation Movement by building the communication network fostering gay identity. The new Gay Liberation Movement, which was much more militant than most homophile organizations, broke with its forbearers in style—opting for protest marches and revolutionary rhetoric over the publishing and the homophile’s traditional nature. As the Liberation Movement became the confrontational face of homosexuality, gay-friendly establishments that had advertised in The Phoenix stopped contributing. Flagging revenues, the overwhelming cost of the Phoenix House, and divided aims led Shafer to end the Phoenix Society for Individual Freedom in 1971.

The fact that Shafer’s Phoenix Society was no more did not stop him from agitating for gay rights in the 1970s and 80s. He continued meeting with student groups and was the first speaker brought in by the University of Missouri-Kansas City’s first gay rights organization, the Gay People’s Union, in 1975. In 1976 Shafer and Ray marched in protest of the Republican National Convention held at Kemper Arena. The next year, they also participated in a rambunctious march when the fervently anti-gay organizer, Anita Bryant, brought her “Save Our Children” campaign to the Midwest—marching in Columbia and Kansas City.

As the Liberation Movement of the 1970s moved into the AIDS crisis of the next decade, Shafer and Ray experienced what almost everyone in the gay community had: the loss of cherished friends. Always intent on improving the lives of their community, they decided to volunteer at an AIDS hospice center in Kansas City to do what they could. As required of all volunteers, both had to take an HIV test. Ray was negative, but Shafer tested positive in the summer of 1986. “It was the first time I’d ever seen Drew truly bleak about anything. He was very frightened and incredibly not for himself, but for me,” Ray recalled. He struggled through the next year, battling depression, weight loss, and general sickness. Shafer collapsed on the morning of September 30, 1989 and Ray rushed him to the hospital. He received a final transfusion and regained consciousness long enough to apologize, “as though he were an inconvenience to me,” Ray remembered. Around dinner time, he finally let go. Ray, Phyllis and Robert Shafer, and dozens of old friends and Phoenix members spread his ashes in the Rose Garden at Loose Park. He was fifty-three.

The five years of 1966-71 represent the great bulk of Drew Shafer’s involvement in the Gay Rights Movement, when he spent nearly every hour of free time advancing the cause, building a conscious gay identity in Kansas City, and building a politically motivated community in Kansas City and contributing to a national network of similar persuasion, Shafer laid the foundation for the Liberation Movement and the gay community would never look back.