Jon D. Barnett was an activist in Kansas City for the lesbian and gay community from the late 1980s into the early 1990s. He wrote for The Alternate News, a gay publication out of Kansas City, MO, and he was a founding member of the ACT-UP (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) chapter in Kansas City – part of a nation-wide coalition responding to the federal government’s inaction towards the AIDS crisis. In 1990, Barnett became the first openly gay candidate to run for a Kansas City city council seat, at about the same time that he took a position writing for The Lesbian and Gay News Telegraph.

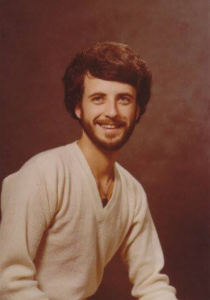

Jon D. Barnett

by Austin R. Williams

In the summer of 1988, Jon D. Barnett marched back and forth in front of a Kansas City convenience store, yelling “Shame!” In the days preceding this one-man demonstration, the Circle K Corporation had cut off medical coverage for employees diagnosed with AIDS. Claiming that the disease’s disproportionate impact upon gay men meant the illness resulted from a “lifestyle choice,” the company was unapologetic in its stance, infuriating gay men all over the country, including Barnett.

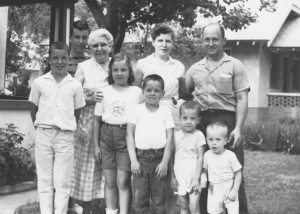

Jon Barnett was the son of a wheat farmer from Colby, Kansas, where those who were different “weren’t easily embraced,” he recalls. His introverted mentality made him the target of constant bullying and harassment. As a teenager, he struggled with his sexual identity, trying desperately not to be gay. He left home at the age of nineteen to live with his older brother in Arizona, who supported him through his coming out period. In 1978, his older sister invited him to come work for her company in Kansas City. Shortly thereafter, he found work as an administrative assistant at the Metropolitan Community Church where he met his life-long partner Michael. He felt at home in Kansas City’s gay community, with its numerous bars along Broadway and Main that catered to a gay clientele, and a handful of parks that served as cruising spots for gay men to meet each other. While sitting in his car at one of these cruise parks, Jon heard the words “gay cancer” for the first time.

In 1981, newspapers across the country reported that doctors had discovered a perplexing new disease (eventually called AIDS) afflicting gay men in Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco. The first case in Kansas City was reported on October 14, 1982. When doctors officially identified the disease the following summer, it still evaded easy definition or categorization. By July 1983, a national average of 165 new cases were reported each month, yet the Kansas City Health Department had only identified four local cases. Within a few months, however, as many as 150 people in the metropolitan area were suffering from symptoms that resembled the disorder in its developing stages.

By 1986, Kansas City’s homosexual men, in particular, were losing loved ones at an alarming rate. In the closing weeks of 1986 representatives of groups including the Good Samaritan Project, Catholic Charities and the city Health Department asked Mayor Berkley to establish a task force to increase public awareness of the disease and begin educating the public about its prevention. Berkley accepted their recommendations, AND after a few months, the Mayor’s Task Force on AIDS (MTFA) held its first full meeting on April 24, 1987.

By now, Jon Barnett wrote regular articles for The Alternate News, a gay publication out of Kansas City, Missouri. An avid reader, Barnett consumed stories about issues affecting gays and lesbians in publications like The Gay Community News out of Boston and The New York Native out of New York. Through these periodicals he learned of an activist group called the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), which took to the streets of New York in massive protests beginning in March 1987.

Barnett put an ad in The Alternate News asking for individuals interested in forming an activist organization to contact him and schedule a meeting. The handful of men who came to that first meeting were just as eager to get to work as Barnett. Some of them had already helped co-found a gay and lesbian organization, the Pink Triangle Political Coalition (PTPC), in Kansas City eight months earlier. By the end of the meeting, they agreed that it was time to form an ACT UP chapter in Kansas City (ACT UP/KC).

Within thirty days they were out on the streets, putting fliers on cars at every gay bar in town and placing weekly ads in the multiple gay periodicals distributed in Kansas City. They protested outside of two Circle K convenience stores, circulated petitions demanding a reversal of policy, and called for a boycott of the store. In mid-September, Circle K rescinded the policy of denying health insurance benefits to AIDS victims. Writing in The Alternate News, Barnett boasted that “[ACT UP/KC’s] confrontational actions, combined with efforts of other groups from Tampa to Phoenix, and individuals across the country resulted in the demise of this atrocious policy.” For Barnett, this news confirmed that his actions could make a difference.

Within thirty days they were out on the streets, putting fliers on cars at every gay bar in town and placing weekly ads in the multiple gay periodicals distributed in Kansas City. They protested outside of two Circle K convenience stores, circulated petitions demanding a reversal of policy, and called for a boycott of the store. In mid-September, Circle K rescinded the policy of denying health insurance benefits to AIDS victims. Writing in The Alternate News, Barnett boasted that “[ACT UP/KC’s] confrontational actions, combined with efforts of other groups from Tampa to Phoenix, and individuals across the country resulted in the demise of this atrocious policy.” For Barnett, this news confirmed that his actions could make a difference.

In early 1989, ACT UP/KC targeted the Telecheck company for firing an employee with AIDS named Mark Sweetland. On March 2, members of ACT UP/KC protested outside of Telecheck’s building in Overland Park, Kansas. Barnett announced to the crowd, “AIDS has been used to fuel the fires of homophobia, leading to even more harassment and gay-bashing. Yet, in response to hatred and tragedy, Gay men and Lesbians have led the way in confronting the crisis with intelligence and compassion. In the face of bigotry and AIDS, we set an example of love and healing for all people.” Telecheck got the message, and by the end of April 1989, Mark Sweetland accepted a settlement with the company.

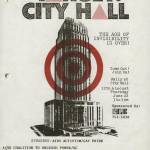

On June 22, 1989, while the City Council met on the 26th floor of City Hall, on the steps below, speaking over a microphone in front of a black banner which read “SILENCE = DEATH,” Jon Barnett demanded that AIDS research, education, and patient care become a top priority in state and federal financing. “All we ask is that we be supported, not thwarted, in our efforts to stop AIDS,” he told those in attendance. Two weeks after this demonstration, the Kansas City Times ran a special edition dedicated to the city’s response to the AIDS crisis. The photographs selected from the demonstration included one of a skinny young man with dark hair and a full mustache. Underneath, the caption read, “Jon D. Barnett is an angry young man.”

On December 6, 1989, BARNETT and fellow ACT UP/KC member David Weeda were invited to speak in front of council members Frank Palermo and Dan Cofran. They made their case that the time had come to amend Kansas City’s civil rights ordinance. Later that month, Barnett and Weeda co-founded the Human Rights Ordinance Project (HROP), with the goal of passing an ordinance which would prevent discrimination against those with HIV/AIDS and also discrimination based upon sexual orientation. Councilwoman Katherine Shields became a strong ally, as did Councilman Dan Cofran.

For a few months, Barnett committed to both the HROP and ACT UP/KC. Rifts were growing within the ranks of ACT UP, however, as some of their tactics became more extreme. The tension grew when a few ACT UP members set fire to a Vatican flag outside of a demonstration at a downtown Catholic Church in March 1990. Shortly after this incident, Jon Barnett officially cut ties with ACT UP/KC.

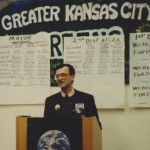

In April, Councilwoman Shields and Mayor Berkley introduced Ordinance #65430 – legislation which outlawed discrimination against homosexuals or people testing HIV positive. At the end of the summer of 1990, Jon took a position as a writer with The Lesbian and Gay News Telegraph, a publication distributed throughout the Midwest. He continued working with the HROP board in developing a strategy for passing an ordinance, and in November the Kansas City Council passed an ordinance protecting gay and lesbian city government employees and also those afflicted with HIV. As the year came to a close, the Greater Kansas City Greens Party decided it wanted to run an openly gay candidate, Barnett, for the Kansas City Council.

Barnett managed to raise a considerable amount of support, garnering 11 percent of the votes in the primary. Despite not winning the council seat, Barnett told readers of The Alternate News, “I believe we have reason to celebrate a victory.” He built a database of every precinct in the city where he did well, and future openly gay candidates for state representatives in Missouri, like Tim Van Zandt and Jolie Justice, used the data in their own campaigns. For Barnett, the council race validated all of the hard work he and others had put forth over the previous two years. “Each success created a new step. And at first, I don’t think we saw a stairway, but eventually we got above the clouds a little.”

In June 1991, Barnett resigned his position as the co-director of the HROP in order to concentrate full time on writing for The News Telegraph, and yet that same month he was appointed to Mayor Emanuel Cleaver’s Commission on Gay and Lesbian Concerns. In just ninety days, the commission completed surveys and produced a report to the mayor with numerous recommendations, including the reiteration that Kansas City still needed to add “sexual orientation” to its civil rights ordinance. When the ordinance eventually passed in June 1993, Barnett immediately wrote an article for The News Telegraph exclaiming “finally!”

In 1994, the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation presented Jon Barnett with a leadership award for his council run and his work as a writer and associate editor of The Lesbian and Gay News Telegraph.[i] Upon receiving his award, he cautioned everyone in attendance that when it came to the struggle for human rights, there was much work yet to be done. Many opponents of the civil rights ordinance vowed to repeal the measure, and despite the gains which had been made in helping those afflicted with HIV/AIDS, the disease continued to take a heavy toll on the gay community.

Decades later, Barnett admits that the work is still not over, although he never could have imagined how much progress would be made in such a short amount of time. While his years as an activist were few in number, he emphasizes that “it seems like those years were essentially my whole life.” He stresses that his story is just one of many; that dozens of great individuals fought alongside him.