Esther Brown was instrumental in the fundraising, organizing, and legal efforts involved in bringing desegregation in schools to the attention of the supreme court. Her earliest and most influential activism was her work in South Park, Kansas, and the Webb v. School District 90 court case in the late 1940s and into the early 50s. Brown also influenced the founding of the Kansas State NAACP, and she was eventually elected to its board of directors.

Esther Brown and the Kansas School Desegregation Battle

by Deborah Keating

The history of “Free Kansas” is replete with examples that belie the state’s early reputation as racially tolerant and a haven for African Americans. Probably the most well -known is the United State Supreme Court’s school desegregation case, Brown v. Board of Education. Yet the tradition of black Kansan’s resistance to white hegemony began long before Brown and the national civil rights movement it powered. The fight for equal education in Kansas manifested itself repeatedly in small, localized court battles. The most important of these was the 1948 fight led by Esther Brown to integrate the elementary schools in South Park, Kansas. The South Park black parents not only lacked the money to sustain the protest, but they also lacked experience in organized, effective activism. Both deficiencies were resolved when Brown joined the battle. She provided leadership and encouraged the parents to expand the protest by boycotting the Jim Crow school. She also raised the majority of the money to sustain the lengthy legal battle. While the case initially revolved around the equality of school facilities for black and white children, it soon grew into a direct attack on Kansas’s Jim Crow school segregation practices that would pave the way for the more recognized Brown v. Board of Education.

Had the town not built a new, modern school for its white children in 1947, the long-held practice of segregation in South Park most likely would have gone unchallenged. Local African Americans, whose property taxes helped pay for the school, objected to their children’s exclusion from the new facility. The school’s condition had deteriorated over time, and compared to the new school for white children built in 1947, the C. J. Walker, black School was a disgrace. To add to the insult, contractors dumped debris from the destruction of the old white school on the C. J. Walker School’s playground. The school’s basement flooded in the rain and the boiler went out requiring cancellation of classes. The deplorable condition of the school’s outhouses was a major topic in the court testimony.

When whites refused to respond to any of the black parents’ requests to correct the C. J. Walker School’s deficiencies, the parents hired Kansas attorney William Towers to file a lawsuit against the school district. The lawsuit, which became Webb v. School District 90, demanded the rights promised under the Kansas Constitution, which prohibited segregation of elementary schools based on race. Attempting to deflect the lawsuit, the school board held an emergency meeting during which it redrew the boundaries of the two elementary schools, effectively isolating all the black families with elementary school age children.

It’s at this point that Esther Brown became interested in the case. Brown’s maid, Helen Swann, lived in South Park and her children attended the Walker school. As she watched the board continue to deflect Swann and the other families’ demands, and after her experience at the South Park school board meeting, Brown was on a mission.

The South Park struggle was not the first experience in activism for Esther Brown. Born in Kansas City, Missouri, the daughter of Russian immigrants, Brown’s father immersed her in Socialist ideology from an early age. It was Esther Brown who convinced the South Park parents to form an NAACP branch, and it was she who managed to get the national NAACP to agree to assist with the case.

Brown also lobbied the South Park black families, urging them to engage in the boycott of the C. J. Walker School. After she convinced them to boycott, she committed to shoulder the primary responsibility for raising the funds needed to pay the teachers’ salaries and support the operation. Brown put all her energy into raising funds through civic groups, NAACP branches, and individual donations to pay the school’s expenses.

Not only did the group need money for the school, it needed money to pay its legal fees. Brown threw herself into her role as primary fundraiser, traveling all over Kansas speaking to NAACP branches, veteran associations, labor unions, and churches telling the South Park story and asking for donations. When her fundraising fell short of the monthly goal, she borrowed money from the national NAACP. When that organization could not provide additional funds, she took out a personal loan.

The organizational skills Brown learned from her earlier activism proved invaluable in the South Park struggle as she networked throughout eastern and central Kansas, building contacts and arranging publicity for the South Park cause. Brown received a great deal of attention in Kansas City’s black newspaper, The Call, for her work on the Webb case. She developed a friendly relationship with Lucile Buford, assistant editor of The Call at the time.

The Kansas Supreme Court finally heard the case and rendered its decision in June 1949, after the school year was over. The Court ordered the South Park school district to redraw its school boundaries along more logical lines, and until then, ordered that it must integrate the new South Park School. The court did not address the NAACP’s arguments that separate-could-never-be-equal but instead focused on the illegal gerrymandering of the school district boundaries to dodge the issue. The judge in the case, Walter A. Huxman was also the judge several years later in the first Brown v Board of Education trial at the state level. In both instances, he avoided a direct confrontation with the issue. Speaking about the Brown case, he later told Kluger that, “If it weren’t for Plessy v. Ferguson, we surely would have found the law unconstitutional. But there was no way around it – the Supreme Court had to overrule itself.”

After the Court’s decision, the school board approached the Court with a new plan. The board proposed upgrading the Walker School over a five-year period. In exchange for its commitment to do this, it requested the Court’s approval of a plan whereby parents could select the school they wanted their children to attend. However, once selected, the child could not be moved to an alternative school without the school board’s permission. The Court agreed to this plan in a supplemental ruling that should African-American parents voluntarily choose to send their children to C. J. Walker School, it would allow it. The school board undertook a door-to-door campaign to “convince” the African-American parents to register voluntarily for the C. J. Walker School in September. Brown launched a counter-campaign. She fully understood that white parents would never elect to send their children to the Walker School, even with improvements and that the end result, if the school board was successful, would be a continuance of segregated schools in South Park.

On September 9, 1949, despite the pressure from the white community, every African-American elementary school aged child in the South Park district marched into the new south Park School and registered for classes. Riding the wave of victory, Brown assembled the five students just graduated from “the boycott school,” dressed them in new shoes and clothes, and escorted them to the segregated Shawnee Mission High School to register for classes. The principal admitted the children without incident.

Brown and the black families of South Park risked personal harm by contesting Kansas’s racial status quo. Early in the protest, one woman “sweetly” reminded Brown that the Klu Klux Klan was still active in the area. In addition to harassing phone calls and hate mail, Brown’s husband, Paul, described how an unknown person burned a cross in their yard. One man advised the Browns to withdraw from the fight, suggesting that Paul Brown would lose all of his customers at his auto parts business if they continued.

After the case’s conclusion, the Kansas State NAACP elected her to its board of directors. The NAACP was ready for a head-on challenge to the separate-but-equal doctrine of Plessy and needed a test case to take to the U.S Supreme Court. Kansas was seen as a prime target because its constitution forbade segregation of elementary schools by race, although the practice was rampant throughout the state. Brown’s role was to identify the next segregated Kansas school district to confront. Her first choice was Wichita, but the black teachers took control of the local branch of the NAACP and voted against the plan fearing the loss of their jobs.

Black teacher’s concerns were not unfounded. As attorney Earl Thomas Reynolds of Coffeyville reminded Robert Carter, “In Graham vs Board of Education of Topeka. . . Negro Teachers were cut adrift without any consideration and they had yrs on their retirement.” In his letter, Reynolds pointed to other examples in Kansas where integration resulted in “qualified teachers holding Masters degrees” losing their jobs to white teachers. When Brown turned her sights on Topeka, she ran into the same wall of resistance from the Topeka teachers she encountered in Wichita. In this instance, however, the local NAACP chapter was led by M.L. Barnett, a man determined to bring integration to the Topeka school. To assist him, Brown used members of the team with whom she worked during the South Park struggle as a foundation for the local effort.

Brown’s value to the national office was far greater than logistical work. When Robert Carter learned, to his dismay that the Topeka branch had only provided $100 in funding since the case began, he called on Esther Brown for help. In his appeal, Carter told Brown, “I know that you have a great deal to do, but it would be most helpful if you would manage to . . . map out a plan for getting this $5,000 raised and sent to us as soon as possible.” Soon as possible meant by October 2 when the appeal had to be filed. By September 1951, after losing the Kansas decision, and with court costs and travel expenses for the appeal looming, Carter also sent letters to many of the local NAACP branches asking for donations to the Topeka cause.

Esther set out to raise as much money as she could as quickly as she could. It is clear that her organizational and fund-raising skills, honed in the South Park protest, were essential to Brown’s success. When the Topeka community gathered outside the Monroe Elementary School on May 19, 1954 to celebrate the Brown decision, Esther Brown was on the podium and she spoke to the crowd. She told them, “It is the ‘little people’ like us who bring about such things as Monday’s Supreme Court opinion. The most brilliant lawyers couldn’t have succeeded but for the help of people like you here tonight.”

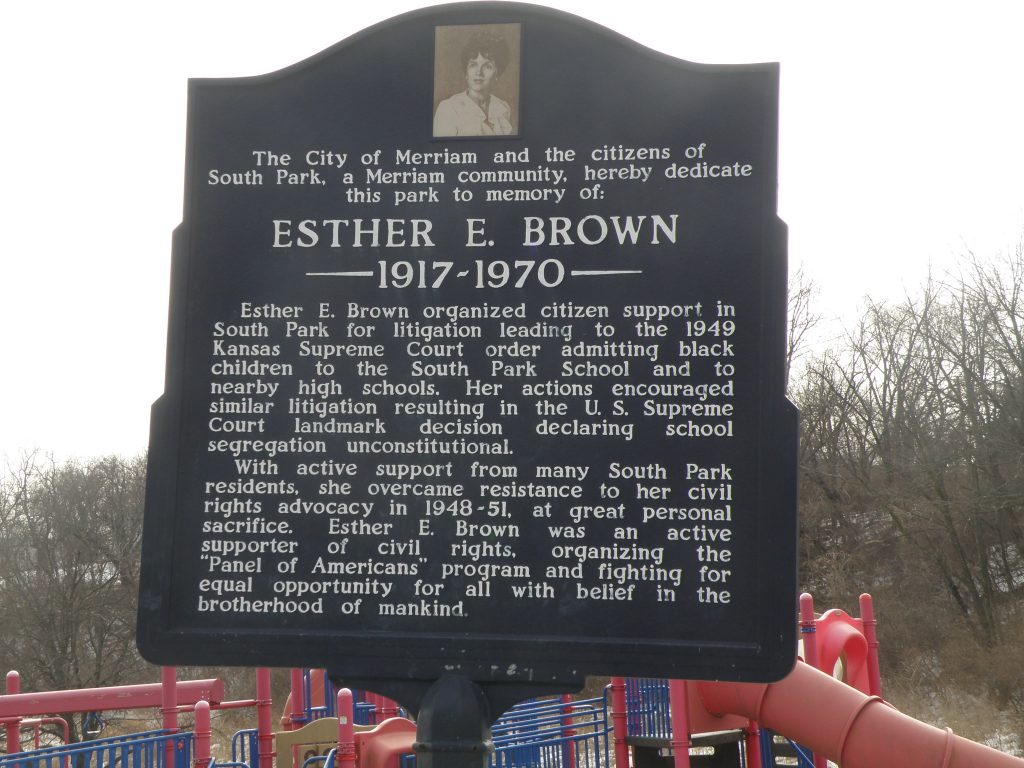

The publicity surrounding Brown v. Board of Education quickly obscured the importance of precursor cases like Webb. As well, the role ofEsther Brown, and the team of Kansas lawyers and activists that she mobilized for the Brown case, was almost forgotten in the attention given Marshall, Greenberg and the NAACP. Most histories of the school desegregation battle do not mention the Webb case at all, but the small community of South Park did not forget Esther Brown. In 1975 the city of Merriam hired Alfonso Webb to construct a park across from the C. J. Walker School building and named it in Esther Brown’s honor.

Activism and resistance have many faces. Brown became a career activist: one who operated outside an organizational structure, such as the NAACP, and moved from social cause to social cause. The South Park battle not only ignited in her a passion for activism, but also provided a core team of trained black activists for the fight in Topeka that became Brown v. Board of Education. It equally demonstrates the importance of women in the civil rights struggle, too frequently overlooked in the better-known story of a southern, male-dominated movement narrative. Both the South Park and the Topeka stories are examples of successful inter-racial collaboration against injustice in a pre- Brown America that drew its energy from the women who simply would not surrender to the status-quo.