Martha Jane Starr was once the foremost advocate for family life research and education in Kansas City. Preventing the breakdown of families through education was her mission. Starr’s efforts culminated in the creation of the Family Study Center, whose many programs benefitted thousands of Kansas Citians in their quest to make family work.

Making Family Work: The Activism of Martha Jane Starr

By Elizabeth Hartzler

Born in 1906, Martha Jane Phillips grew up in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. Daughter of L. E. Phillips, she was heiress to the Phillips Petroleum Company and traveled the world as a young woman. Unlike her two older brothers, Phillips did not receive a university education. Instead, she attended a finishing school in Boston at her father’s request. “They called it ‘finishing’ school,” she said, “as if you were ‘finished’ after that, or hadn’t been ‘finished’ before.” L. E. Phillips subscribed to the Victorian belief that higher education was not proper for women. For Martha Jane Phillips, this was a missed opportunity that she would always regret.

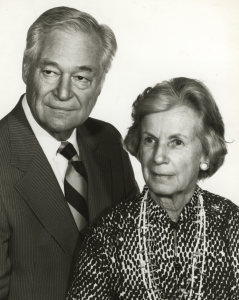

Martha Jane married John “Twink” Starr in 1929. John Starr was a geologist who worked for L. E. Phillips in Bartlesville, Oklahoma where the couple lived before moving to Kansas City. World War II took John Starr into the Army and overseas. During his absence Starr began her long history of volunteerism in Kansas City; first at the Red Cross, then at Pembroke Day School, the Junior League of Kansas City, and many more organizations. “Everything to which Martha Jane belongs she brings a great sense of organizational drive and dedication,” said one admirer.

In 1947, Starr became deeply involved in Planned Parenthood. An organization that Starr described was “about the wanted child,” Planned Parenthood Great Plains was only twelve years old when those at the organization approached Starr about volunteering. She served on the Kansas City chapter’s board and then as president both locally and nationally. Due to Starr’s association with Planned Parenthood, she was able to establish a Professorship in Human Reproduction at the University of Kansas Medical Center. This partnership was not a natural one. The medical community believed that by associating with Planned Parenthood, it would be accused of being “anti birth.” Research on reproduction was a largely taboo subject during the first half of the twentieth century even within the medical community.

Starr and Georgia Nielson, whom she met while working with the Red Cross, quickly discovered how problematic this subject was when they took on the responsibility of finding supporters. Starr described the reaction that many of the men they approached had by saying, “Sometimes they would look at us as if they wondered why our husbands let us out of the house to do this kind of thing.” Starr and Neilson, however, persevered and were able to raise the funding needed to endow this professorship, the first of its kind in America. The research produced by this professorship would later aid in the creation of the birth control pill.

Starr’s time at Planned Parenthood demonstrated what a grievous lack of education existed not only regarding reproduction but concerning interpersonal relationships as well. “The problems which families encountered were more complex than a pill, or even a law, could remedy,” said Starr. Starr’s first endeavor was a program called “Education for Marriage.” This program was marginally successful and did not have the research component that Starr knew was the path to greater change.

The relative failure of this pilot program was crushing for Starr and those who had supported her. When in the wilderness, however, it does no good to wander. Instead, Starr found a guide by the name of Dr. David Mace. Popular with the public and respected within the field of sociology, Dr. Mace began his life’s work in marriage enrichment in England by developing the National Marriage Guidance Council. Dr. Mace believed that the ideal time to save a marriage was before significant problems developed, yet few preventive programs existed. In 1960, Starr met Dr. Mace at the White House Conference on Children and Youth, which began a lifelong friendship between the Starrs and the Maces.

In 1959, with the guidance of Dr. Mace, Starr and twenty-one other concerned individuals, along with several family life organizations, opened the Research Center on Family Development. As part of the Institute for Community Studies, a non-profit private research agency, the center’s goal was to conduct research concerning couples and family life, establish points of weakness, and determine ways in which those problems could be prevented.

World War II led to an abundance of war marriages in the United States. Characterized by their spontaneity, war marriages became not only prevalent, but problematic. Starr often cited rising divorce rates and delinquency in youth, trends which sparked the second great marriage crisis in America during the twentieth century. A host of experts, both qualified and merely popular, sought to curb those tendencies.

Between 1959 and 1963, the Research Center on Family Development performed research, developed programs, and published on marital and family issues. Despite this, they found it difficult to gain members. Without the backing of a trusted institution, the center’s growth stagnated and funding was increasingly difficult to obtain. Starr sought a way to acquire the necessary financial and institutional support. The answer came from the recently renamed University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC). In 1963, the Research Center on Family Development merged with UMKC and was renamed the Family Study Center.

The opportunity to direct a new Family Study Center brought Dr. Oscar Eggers from the University of Chicago to UMKC in 1963. It is easy to hear Starr’s voice reflected in the center’s mission statement as it was her belief that “the family is the primary institution for the personal growth and development of the individual and is the stabilizing force for society as a whole.”

While the programs developed by the Family Study Center covered every segment of society, Starr seemed most eager to work with those concerning the disenfranchisement of women. One such program was called “Increasing Competence of Economically Deprived Mothers.” In Starr’s words, the economically deprived mother was caused by “…a failure within the society to develop significant knowledge about human relationships.” This program studied the ability to develop autonomy and empathy with the hope that this could lessen an individual’s reliance upon welfare. Starr was also personally involved in “Motivation for Self-Development of Teenage Girls.” This project “…worked with inner city teenagers in an effort to help them achieve a better quality of living.” The program consisted of small group discussions on topics like employment, family life, education, and community opportunities.

Even though the Family Study Center had the stability of UMKC, Martha Jane Starr knew it needed independent advisors who would look out for the best interests of the center. In 1964, Starr helped form the Family Study Center Advisory Board of which she was chairwoman for the first ten years. The Advisory Board suggested areas of programming or research, and evaluated said programming for effectiveness. In addition to her gift for volunteerism, Starr was a business woman, adept at running an institution and tireless in her devotion to it.

The Family Study Center Endowment Fund was one such project on which Starr worked tirelessly. “The purpose of this fund is twofold,” stated Starr, “–first to give recognition to the importance of special interest in Behavioral Sciences, and secondly, to make permanent and enlarge the Center’s program activities, particularly in Women’s Education.” The endowment not only allowed the center to cover its own research and program development costs, but also to offer grants to other local organizations for family life programming. One of the programs made possible by the endowment was the “Community Committee for Unwed Parents” (C-CUP). Created in 1968, C-CUP focused on the prevention of unwed parenthood but also created opportunities for unwed teenage mothers to continue their education. C-CUP influenced a more flexible class attendance policy for pregnant high school girls within the public-school system and increased the number of support services, such as clinics, that were available to them.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the Family Study Center came into its own. In the first eight years of its operation, it is estimated that over 25,000 people participated in its programs. Programming statistics for 1972-1976 alone resulted in twenty-seven community presentations, and thirty-two presentations for professionals. The Family Study Center also conducted a number of credit and noncredit classes for graduate students, including one experimental class on marriage enrichment. This course was geared toward practical marital enrichment of the student or couple enrolled in the class. Starr’s conviction regarding the importance of prevention was being scientifically validated. Longitudinal studies revealed that prevention oriented programs were proving effective.

Martha Jane Starr served as president of the Family Study Center for its first twenty years and was part of every board and council that supported it, including the Community Advisory Council, the Community Consultants’ Council, and the Family Study Center Executive Committee.

In 1967, Starr and seven other women founded the Women’s Council, a program near to Starr’s heart. Starr recounted that one of the first Women’s Council projects was to plant flowers. Beautification was seen as an appropriate task for women at the university. “That was one of the first things we talked about,” stated Starr. “We were going to do more than plant flowers.” While Starr was a lover of nature, she recognized that this was a chance to encourage women to pursue their own academic degrees and careers. Just as the Family Study Center had been Starr’s opportunity to aid in strengthening families, the Women’s Council was her opportunity to fulfill her other great passion, assisting women at the university.

Starr was adamant about promoting equal treatment for women, not just in marriage but throughout society and especially in the academic world. There was a striking lack of available financial resources for women at the university. Therefore, Starr created the Graduate Assistance Fund, which drew on the Family Study Center Endowment in order to offer scholarships to women in need.

Exactly ten years after the creation of the Women’s Council, the Women’s Center opened as another by-product of the Family Study Center. The Women’s Center focused on providing support to female students and faculty through workshops, presentations, and lecture series. Starr inspired the Women’s Center with her passion for education, even though she was not as involved as she was in the Women’s Council. The Women’s Center continues to host an annual symposium on women’s issues and other family life concerns, named the Starr Symposium in honor of Martha Jane Starr.

In 1991, the Family Study Center closed its doors due to dwindling interest and the reorganization of various UMKC departments. Many of the center’s spin-off programs carry on its work and remain vital parts of the university and community. The Women’s Council and Women’s Center are still in operation and thriving, along with the Starr Symposium. The Graduate Assistance Fund has aided over 1,700 women in their quest to receive higher education.

Throughout her many years of serving the Kansas City community, Martha Jane Starr’s work did not go unnoticed. In 1968, she was the first woman to receive the UMKC Chancellor’s Medal. Starr was also awarded the Mace Medal in 1982 for her outstanding achievements in marriage enrichment. Planned Parenthood and the Junior League also honored Starr for her lifetime of service to the Kansas City community. In 1992, Starr received an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters and an Honorary Minor in Women’s and Gender Studies from UMKC.

It is estimated that Martha Jane Starr volunteered for or was a part of over one hundred different institutions during her lifetime. Starr’s archival collection contains folder upon folder of saved thank you letters, physical evidence of how many lives she touched. Starr passed away in 2011, just shy of her 105th birthday, yet her legacy lives on. Just as the Family Study Center produced waves of impact and enrichment throughout the community, so did Martha Jane Starr. They have yet to fade.