Bobby Blue, a Choctaw Indian originally from Oklahoma, and Nancy, his wife, were leaders in Kansas City’s American Indian community since the early 1960s. The Blues were integral in starting the first American Indian social club in Kansas City and later the city’s first federally-funded non-profit organization – the Heart of America Indian Center (HAIC).

Indians at the Crossroads: The Native Activism of Bobby and Nancy Blue

by Joshua Mika

High rates of poverty, alcoholism, and malnutrition plagued Kansas City’s Indian community in the latter half of the twentieth century. Through the HAIC (Heart of American Indian Center) and other endeavors, Bobby and Nancy Blue sought to ease some of the glaring problems Indians experienced after they moved in large numbers from impoverished reservations and relocated to urban centers, such as Kansas City. Kansas City proved a unique case given its central location and relatively close proximity to large Indian reservations in Oklahoma. Kansas City became a destination for many destitute Indians who sought economic answers to their plight in a time when the cards were stacked against them.

Between the 1940s and 1960s, the federal government began a process of terminating its official relations with many Native American tribes in order to abjure the government’s responsibility for Native American security and well being. The planners behind this scheme sought to reshape America’s indigenous peoples as “equal” minority citizens who held no special government status. The federal government actively encouraged Native Americans to relocate from reservations to larger urban cores in order to spur cultural assimilation and improve their economic conditions. This scheme proved disastrous for Native Americans in the twentieth century.

As a poor Choctaw Indian from a broken home in Oklahoma, Bobby Blue’s story of migration and assimilation was no different. Bobby was born in Oklahoma in 1936. By his early teens his parents had divorced, and Bobby and his older brother, Jim, found themselves in an Indian boarding school separated from both parents. The boys struggled to assimilate to harsh boarding school life, refusing to eat and becoming despondent in the school’s martial environment. Alarmed at their refusal to adjust, school officials contacted the Bureau of Indian Affairs to send the boys to a different location. A local Creek Indian pastor accepted Jim as an orphan, and the boys’ father reluctantly agreed to raise Bobby.

Nancy Blue discussing Bobby and his father

Bobby and his father migrated to Kansas City in the early 1950s to seek better economic fortunes. “It was a white man’s world, and you had better forget any of your Indian ways if you want to make it in this place,” Bobby’s father told him upon their arrival in Kansas City. Both father and son struggled to make ends meet in their new lives. In 1956, Bobby agreed to chaperone a double date and ended up meeting his future wife, Nancy. What started as a chance encounter between two strangers ended up a mixed-race marriage between Bobby and Nancy during a time of pronounced racial tension in the United States.

By the time Nancy and Bobby started seeing each other regularly, Bobby’s father sank into deep alcoholism, which consumed what little money he earned. After finishing his junior year at Rockhurst High School, Bobby dropped out of school to support his father.

Born in Belleville, Kansas in 1939, Nancy’s family moved to Kansas City when she was fifteen. “I grew up in an all-white town in Kansas…we never thought about anybody being a different color,” she remarked. “I loved cowboys and Indian movies…but never in my wildest dreams did I ever think I would move from Belleville or marry an Indian!” Upon meeting Bobby, Nancy took an immediate attraction to him and they began seeing each other against her father’s wishes. Her father forbade Nancy from marrying Bobby, insisting that “Indians beat their wives, they don’t come home, they don’t bring the money home, they’re alcoholics, [and he] never met a good one.” Nancy recalled that “Bobby…was a very quiet person…very polite….” Bobby “didn’t drink, and he didn’t smoke, and he was pretty straight laced.” Nancy’s father spent much time away for work, so Bobby used this time to court Nancy and spend more time with her mother and three younger sisters. “He would have supper with us…a lot of times [these were] the only meals he got at night, which I did not realize [at the time],” according to Nancy. Nancy and Bobby’s love blossomed against all odds. After two years, Bobby and Nancy married in August 1957.

Nancy Blue discussing her marriage with Bobby

During the early years of their marriage, Bobby showed no interest in his Indian cultural identity. He took his father’s advice to lose his Indian ways and assimilate into the white man’s world. Marrying a white woman and assimilating to white culture was not enough for Bobby to pass in Kansas City’s racially-charged atmosphere of the late 1950s, however. After taking a job downtown, Nancy’s employer spotted Bobby picking her up from work and giving her a kiss. He threatened Nancy with termination, explaining that dating a “black man” violated the company’s strict anti-miscegenation policy. Nancy protested, stating that her husband was not black, but was, indeed, an Indian. The company official who leveled the charges against them – Ken Powlas – was also an American Indian.

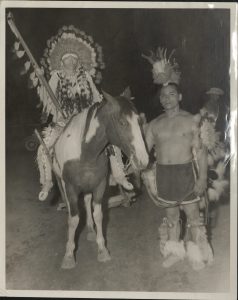

Growing up on Kansas City’s west side, Bobby blended in well with the local Hispanic community and made no attempt to assert his Indian identity. After meeting Ken Powlas, however, Bobby’s attitude towards his own Indian heritage and Indian welfare changed dramatically. The two men became friends, and their relationship put Bobby on a new path—a path to rediscover himself as a Native American. The Blues wanted their three children to experience the culture that Bobby had abandoned. This initial meeting with Ken Powlas spurred greater contact between the Blues and Kansas City’s growing Indian population of the late 1950s and early 1960s – the height of the termination era for American Indians. The Indian families in the area began holding regular Indian powwows where their children could hear their native languages and witness and participate in their cultural practices. Pow-wows provided an essential venue for reaffirming Native identities and providing cultural continuity to marginalized groups in the United States. An efflorescence of Indian culture thus emerged on an unprecedented scale in Kansas City. Greater, more pressing needs of Indian survival began emerging as more and more Indians arrived in Kansas City.

Between 1952 and 1972, more than 100,000 Native Americans had relocated from reservations to urban cores across the nation. Poor Native youth left the reservation after hearing that cities had “streets painted with gold!,” Nancy stated, reiterating a prevailing thought that lured so many Natives away from reservations to the city. In light of an emerging Native population in the metropolitan area, the Blues, along with several other local Native families, established a Native American social club—the Council Fire of Greater Kansas City—in October 1962. “The Club,” as its members call it, still exists today as the Indian Council of Many Nations.

The Club’s founders saw the growing needs of the Native population firsthand. Many Native immigrants themselves were the impoverished relatives of The Club’s founders. People heading to Kansas City from large reservations in Oklahoma and South Dakota oftentimes broke down in transit to Kansas City. “We were shellin’ money out to see that they go where they needed to go, or they got their car fixed…we were the welfare unit, and if any Indian got in trouble in Kansas City, they called,” Nancy explained. Bobby, as president and secretary treasurer of The Club, rounded up any available resources from members on an ad hoc basis to assist migrants.

In addition to these practical services, The Club acted as a social group that allowed Natives a venue for maintaining Native “history, lore, dances, songs, crafts, and ideals of the American Indian.” Nancy could never officially be a Club member as a white woman, however, she did not let this stop her from performing vital duties organizational maintenance for The Club. Bobby served in various capacities, acting as president and later as a board member for thirty years. The organization became active in promoting Native cultural practices fulfilled the Blues’ wish that their children grow up connected to a reemerging Native culture.

The Club had no permanent building or office, and it lacked a central telephone number. Members usually met in church basements or peoples’ homes. Encouraged by the success of the nation’s first non-profit Native American organization in Chicago—the American Indian Center—established in 1953, Club members decided that the pressing needs of Natives in Kansas City necessitated the establishment of a nonprofit organization with a permanent building.

On August 28, 1971, the Heart of America Indian Center officially opened its doors as a nonprofit organization. Many of the same families who established the Club, including the Blues, were also HAIC founders. They used an initial $32,000 Office of Economic Opportunity grant and a $4,500 grant from the National Indian Lutheran Board to rent a building on Independence Avenue and hire two permanent employees. Bobby acted as the chairman of the board. Kansas City Mayor Charles Wheeler addressed the opening ceremony and proclaimed that the day would henceforth be known as “Indian Day” during his tenure in office. The HAIC included services for alcohol addiction counseling, home placement, and offered community outreach classes about Native cultures.

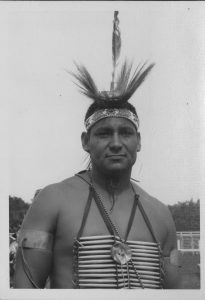

Even beyond Bobby’s work with the Club and the Center, Bobby’s Native dance performances earned him much local recognition. In 1974, Mayor Charles Wheeler appointed Bobby as the Native American representative on the Ethnic Heritage Committee as part of Kansas City’s official participation in the United States’ forthcoming bicentennial celebration in 1976. In 1979, this body morphed into the organization that spearheads Kansas City’s annual Ethnic Enrichment Festival to this day. During his decades-long involvement with the festival, Bobby was able to promote Native cultural awareness – particularly through his talent as a Native dancer – to many who may not have come into contact with native culture otherwise.

By the 1990s, Bobby’s growing recognition as a Native cultural ambassador was evident, and his activism began taking unforeseen dimensions. The Missouri Department of Conservation appointed him as an official Native American adviser in the enforcement of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Passed in 1990, this law stipulated that agencies and museums receiving federal funds must settle all outstanding repatriation matters concerning Native American remains and other sacred objects. Even protection for unmarked Native graves on public lands fell under the purview of this wide-reaching law. In this role, Bobby acted as an attaché between several state bodies involved with the law’s implementation, as well as various Native American tribes whose ancestors’ remains were of concern. Bobby acted in this capacity until his death in 2003. His daughter, Norie, took her father’s position after his passing.

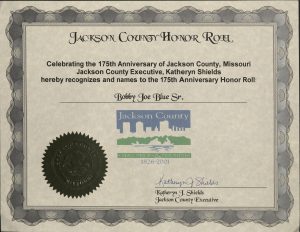

Towards the end of Bobby’s life, he received one of the greatest honors for his activism for Native welfare and his promotion of Native culture in Kansas City. In 2001, Jackson County (Missouri) Executive Kathryn Shields and the Jackson County Historical Society included Bobby’s name on the honor roll of local “history-makers,” created to celebrate the county’s 175th anniversary of its founding. This great honor, which Bobby received in the twilight of his life, reminded all that Bobby refused to allow Native culture, and let alone Native Americans, vanish from the Kansas City landscape. Over a span of four decades, Bobby Blue, with the integral assistance of his wife, Nancy, became one of the most trusted and well-known Native American personalities in Kansas City. “If you talked about an Indian…his name was the first one that came up.,” Nancy recalled. It is their activism that we should honor and remember as an essential feature of Kansas City’s history.

Nancy Blue discussing her husband’s overall impact on Kansas City