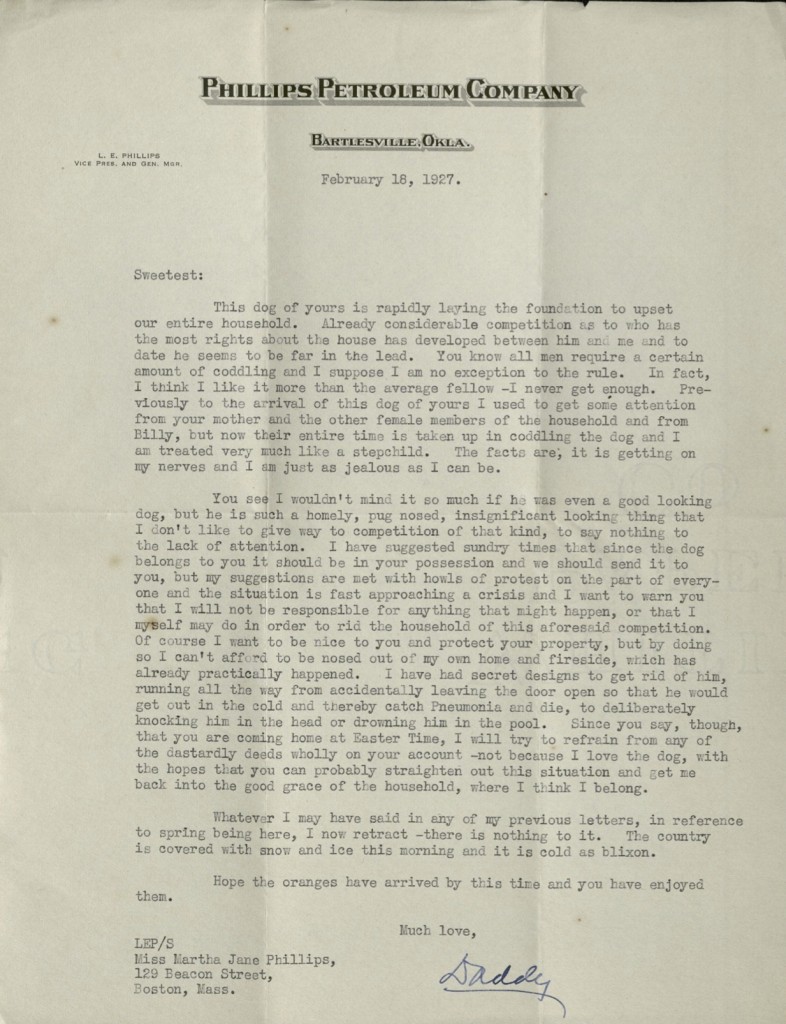

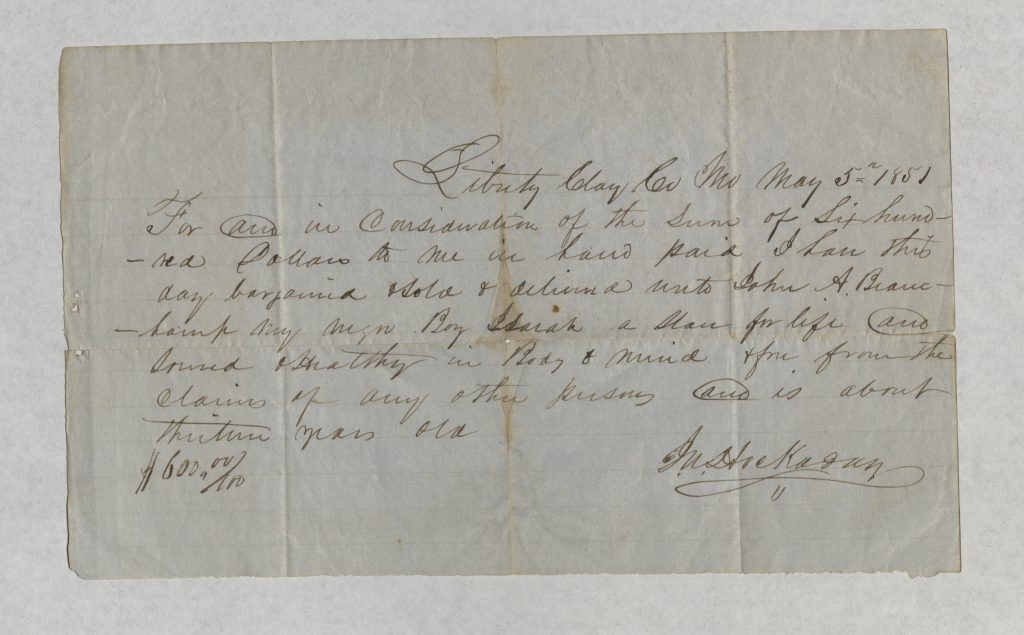

Below is a transcription of the bill of sale that John A. Beauchamp (1817-1901) received on May 5, 1851, when he purchased a slave in Liberty, Missouri. The original is pictured above.

Below is a transcription of the bill of sale that John A. Beauchamp (1817-1901) received on May 5, 1851, when he purchased a slave in Liberty, Missouri. The original is pictured above.

“Liberty Clay Co MO May 5, 1851. For and in consideration of the sum of six hundred dollars to me in hand paid I have this day bargained sold and delivered unto John A. Beauchamp my negro boy Isaiah a slave for life and sound & healthy in body & mind & free from the claims of any other persons and is about thirteen years old.”

This is the oldest item in the J.A. Beauchamp Collection. Most of the items in the collection relate to John Arthur Beauchamp (1895-1953) who served in the U.S. Army during World War 1. (His grandfather, to whom Isaiah was sold, was also named John Arthur Beauchamp – to avoid confusion I will use the first and middle name in reference to the older Beauchamp) We don’t know why John Beauchamp saved this particular document from his grandfather’s life. He was born in 1895, long after the Emancipation Proclamation freed Isaiah. Whatever his reasons for preserving it, this document was a direct connection between him and his family’s ties to slavery. From it, we can learn some things about the economic status of his grandfather’s family.

In Missouri, most slaveholdings were family farms that exploited the labor of only a few slaves, usually fewer than ten. Their small size and diversified agricultural practices distinguish Missouri slaveholdings from their plantation counterparts in states like Mississippi and Louisiana. Owning even one slave was a sign of relatively high wealth and status. The price Beauchamp paid for Isaiah reflects this. No census figures for John Arthur Beauchamp are available prior to 1870. However, according to the 1870 census, he was a wealthy man, with a combined personal and real estate valued at $12,000. The “Economic Status” measurement from MeasuringWorth “measures the relative “prestige value” of an amount of income or wealth measured using per capita GDP. When compared to other incomes or wealth, it shows the relative prestige the owners of this income or wealth because of their rank in the income distribution.” Using that measurement, John Arthur Beauchamp’s wealth in 1870 was the equivalent of just over $3.4 million in 2015. Using the same measurement, the $600 selling price of Isaiah was equivalent to $298,000 in 2015. The “Labor Value” measurement uses either skilled or unskilled wage rates to calculate value. If we think of his $600 sale price as an unskilled labor value (as recommended by MeasuringWorth), it was the 2015 equivalent of $137,000. MeasuringWorth does also feature a more in depth analysis of other ways to evaluate slave prices.

The economic history of slavery is only one facet of a tremendously complex and painful subject. It does demonstrate that slaveholders who betrayed the Union may have done so to protect what they saw as crucial and valuable financial assets. That said, there is no evidence that John Arthur Beauchamp served in the Civil War. Age may have been a factor, as he was between 44 and 46 years old in 1861. There are three letters from the older John A. Beauchamp in the collection, but none addresses slavery directly. In other words, we don’t know why family members preserved it, or how they viewed their ties to slavery. It is theoretically possible that John Beauchamp’s father, Lee Beauchamp (born in 1864) knew Isaiah. Lee undoubtedly knew the black servants listed in John Arthur Beauchamp’s household in the 1870 census. But for now we have no way of knowing what, if anything, Lee Beauchamp told his son about his grandfather’s slaves or what it was like growing up in a former slave owning family in Missouri in the 1860s. Ultimately what makes this document significant is that it raises all these questions. It forces us to confront what our own ties to slavery and the Civil War era might be. Remembering is not always easy, but forgetting or ignoring the past carries far greater consequences.

Sources

J.A. Beauchamp Collection, MS216, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missour-Kansas City.

Ancestry.com