Geosciences Museum and Richard J. Gentile

Richard J. Gentile, Ph.D., is proof that the love of teaching need not end with retirement.

Gentile’s faculty position combined two of his favorite things – students and rocks. As a Department of Geosciences emeritus professor and volunteer museum curator and docent, he continues to enjoy this rewarding mix, showing thousands of visitors through the Geosciences Museum in Flarsheim Hall, Room 271.

The museum opened in 1973, when Dr. Richard L. Sutton and UMKC Professor Eldon J. Parizek – Gentile’s predecessors – assembled much of the collection and display units. Sutton, a dermatologist, was an adjunct geology instructor who gave his personal collection of cephalopods (squid-like ocean dwellers) and fluid inclusions (rocks containing liquids) to the museum. An interactive feature allows viewers to tip the clear quartz and watch the trapped primordial water move.

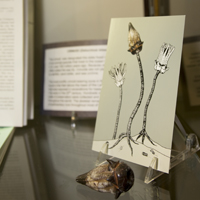

In Gentile’s domain, hundreds of minerals, fossils and ores sit in cases ringing the walls. A source of particular pride is the museum’s Crinoid collection. Crinoids, or “starfish on a stick,” were abundant in downtown Kansas City, once ringed by a shallow sea.

In 1889, excavators discovered at least 400 specimens at 10th and Grand. One hundred years later, at the urging of Missouri school kids, then-Governor John Ashcroft made the crinoid the official fossil of Missouri.

Another curiosity is an enormous fulgurite, or “lightening rock.” Lightning generates tremendous heat – as much as 3000 degrees Fahrenheit. When lightning strikes the earth, it fuses the silicon dioxide in its path into tube-shaped glass. The geosciences museum has just such a specimen, found in Clay County, Mo.

Most of the museum’s fossil collection was amassed by Gentile on trips to the Badlands of South Dakota. Through UMKC’s Continuing Education program, Gentile travels with student groups each summer to conduct research and to look for vertebrate fossils.

Gentile, who began teaching in 1966 and was given emeritus status in 1999, continues to do field studies and write articles; understandably, many of his publications detail the geological and paleontological wonders in his own back yard. According to Gentile, things remain buried in regional sediment and lake beds for a geologist to find and get excited about.

“I found and named a species of coccoliths in 1971 when they were building a stretch of I-29 near St. Joseph,” said Gentile. “They are the remains of one-celled protozoans, visible only with magnification of x 10,000. They are flat and disc-shaped and resemble tiny waffles. I call them ‘Paleococcolithus missouriensis’.”

Kansas also is home to a wealth of fossils.

“When Highway 169 was being built in Kansas, I found a new species of Dentalium that proved they existed 50 million years earlier than previously thought,” said Gentile.

Gentile enjoys exploring around Bethany Falls, a 20-foot-thick limestone bed that extends from Nebraska through eastern Kansas, western Missouri and Oklahoma. The bed was named after the town of Bethany Mo., the approximate midpoint of the rock fall. Kansas City is built on this fall and the Hunt Midwest underground storage is part of it.

At one time, a Bethany Falls ledge served as a natural waterfront wharf in Kansas City, creating an ideal spot in the early 1800’s for riverboats to dock. The Corps of Engineers covered a large portion of this wharf after the flood of 1953, and the formation of Kansas City’s Riverfront Park erased the last of it.

Gentile’s anecdotes are full of the wonder and thrill of discovery. A visitor to the Museum might have a similar sense of discovery, wandering from case to case and spotting wooly mammoth hair, a jaw bone, crystals and geodes. Gentile welcomes them all.

“My best guess is 10,000 young visitors to the museum over the last 30 years. Elementary schools, Cub Scouts and 4-H groups are the most frequent. I talk about many geologic topics with these youngsters, but they keep coming back to the Ice Age mammals with their big, curved teeth and fierce skulls.”

Gentile, like his young visitors, always curious

“I first became interested in geology, specifically paleontology when I was 7 years old,” said Gentile. “A travelling circus came to town, with a ‘man who was turning to stone’ lying in a coffin-like box. His skin was ghostly white. It was probably talcum powder, but it convinced me. I thought fossilization was caused by something in the air, and I decided to fossilize something myself.

“Back home, I put a potato and an apple in the crook of a tree and waited for them to turn to stone like the circus fellow. I got a soggy potato and an apple full of bird bites. My dad suggested I try a cave. New apple, new potato, same results. Cave-dwelling critters ate almost everything. I finally began reading about fossils.”

A word of caution to the younger groups who take the tour … there is a quiz. But the questions are based on the exhibits in front of you – “open book,” so to speak.