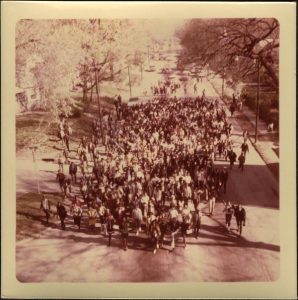

In this photo from the 1968 Riot Collection in UMKC’s LaBudde Special Collections, protestors march down Vine at Flora and Paseo.

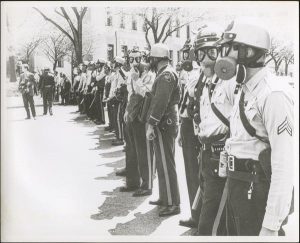

On April 4, 1968, in the midst of nationwide social and political turmoil, Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated. On April 9, the day of his funeral, Kansas City (MO) Public School officials chose not to cancel classes. In protest, students from Lincoln, Manuel, and Central High Schools marched from school to school and finally to City Hall. They were followed by police officers dressed in riot gear. Though it is unclear what prompted police officers to begin firing tear gas on the crowd, the confrontation between police and protestors escalated. By that night, the demonstration had given way to chaotic riots that lasted four days. Many buildings around 31st Street and Prospect burned, protestors and officers were injured, and six African American citizens were killed. The 1968 riots were a painful moment in Kansas City’s history, but they also raised questions and launched conversations about racial tensions and social disparities—conversations that continue today.

(For a more detailed account of these events, see Joel Rhodes’ article “It Finally Happened Here” in the April 1997 issue of the Missouri Historical Review.)

The 50th anniversary of these events this spring prompted articles and documentaries (like this one by KSHB), panels (like the “’68: The Kansas City Race Riots Then and Now” held at the Kansas City Public Library), and exhibits (like this one at the Central Branch of the Kansas City Public Library). KCUR drew attention to the collection in UMKC’s LaBudde Special Collections, and called for help identifying the subjects of the photographs. The unnamed faces and unclear contents of those photos reflected a crucial problem: we needed to do more to preserve people’s memories and perspectives. Photographs and official reports are important parts of the historical record, but so, too, are the recollections of the people who participated.

In this photograph from the 1968 Riot Collection in UMKC’s LaBudde Special Collections, police officers line up outside of City Hall wearing gas masks and carrying billy clubs.

To correct this problem, KCUR’s Director of Community Engagement Ron Jones, Miller Nichols Library Advancement Director Nicole Leone, and UMKC Assistant History Professor Sandra Enriquez teamed up to launch the 1968 Oral History Project, an effort to interview Kansas Citians who experienced or participated in the 1968 demonstrations. Their goal is not only to gather recollections of the protests, but also to understand the broader context of racial tensions and social problems in Kansas City before and after 1968. I was invited to join the project as a graduate assistant.

At our first recording session, held at the Lucile Bluford Branch of the Kansas City Public Library in May, I watched Dr. Enriquez conduct three interviews. Though I am no stranger to interviewing—my background is in newspaper journalism—I was grateful for the opportunity to observe an oral history interview. There are subtle but important differences in the historian’s approach to interviews: Where journalists are focused on the details of a specific event, historians want to pull back and get a bigger picture, understanding the context that motivated the interviewee and influenced their perspective. Reporters are often pressed for time, keeping interviews tightly focused, asking questions that they hope will provoke clear answers and interesting quotes, and focusing on how the interview relates to the story at hand. Oral historians have the luxury of more time to follow the subject down interesting trails of thought. Perhaps even more important, oral historians do not always have a clear goal for the interview, except to preserve the subject’s responses. As a result, historians cover more terrain—I find myself wondering what a future historian will curse me for not asking about during my interviews.

I conducted our second round of interviews on Saturday, June 16, at the Southeast Branch of the Kansas City Public Library. My greatest fear was that, despite my backup batteries and backup recorders, I would run into some technological problem. All went smoothly, though, and I was able to settle in to listening and asking questions. In a future post, I’ll talk more about the interview process, some of the things I am wrestling with in my role as an oral historian, and the challenges of conducting oral histories. For now, though, I will say that it is fascinating to sit and really listen to a variety of people share their overlapping but different stories. Some themes emerge, some of the same names and places come up again and again, but each person also brings a unique perspective, shaped by their families, their experiences, and by their lives after these events.

This is my first foray into oral history, and I am hooked. Maybe it’s the former journalist in me, but the opportunity to engage in a conversation about people’s memories is a powerful experience. Not only do I believe that oral histories complement existing archival sources like photographs and documents, but studying oral history has prompted me to rethink the historical sources I encounter. We often fall into the trap of taking written sources at face value, as moments somehow frozen in time. As I listen to how seamlessly our interview subjects connect the events of 1968 to the social and political struggles facing our country today, I’m struck with the knowledge that all of our experiences and memories are influenced by what came before, and will continue to impact the events that follow. Examining the complicated interaction of context, continuity, and change is what gives history its thrill.

We have conducted six interviews so far. We are hoping to interview far more to gain as much understanding as possible, and one of my jobs is to find additional interview subjects. So please: If you or someone you know would be willing to share your experiences of the 1968 protests and riots in Kansas City, I would be grateful to hear and record your stories. Please reach out to me at kbcm97@mail.umkc.edu. You can also find me on Twitter at @katebcarp.