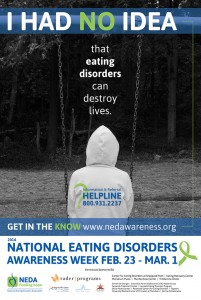

In honor of National Eating Disorder Awareness Week and UMKC’s Every Body is Beautiful Week, this is a guest blog from the National Eating Disorders Association Blog.

In honor of National Eating Disorder Awareness Week and UMKC’s Every Body is Beautiful Week, this is a guest blog from the National Eating Disorders Association Blog.

For more information about UMKC’s Every Body is beautiful Week events, please visit our Facebook page.

By Melissa Fabello, Editor, Everyday Feminism

Pick up any eating disorder memoir at your local bookstore, and you are more than likely to find some iteration of this narrative arc.

Well-to-do, young white woman develops an eating disorder, spirals into near-oblivion, seeks treatment for her eating disorder (which usually results in her being admitted into a residential facility), experiences a myriad of successes and failures, and eventually commits to finding her Self again. Well-to-do, young white woman walks out of treatment with a new sense of hope on the road to recovery.

From a consumer-driven standpoint, it makes complete sense. Of course people are buying (and selling) these stories. Just as we see in our media landscape, there is a huge market for the most extreme and “graphic” version of any issue, and there will be people who are attracted to cathartic memoirs that are moving in that they’re so terrifying. It takes courage to tell your story of struggle with a mental disorder, to confront the stigma. They may be written from a place of good intention to educate and raise awareness about how serious eating disorders are, but they can also have the unintended effect of making us feel better about ourselves, our lives – hell, even our diets. “At least I’m not like that,” or “I’m not that sick.”

From an eating disorder recovery perspective, we have to ask ourselves whether these limiting representations of life with an eating disorder are doing more harm than good in the absence of other diverse voices and experiences with these illnesses. As important and valid as stories like the above are about a commonly misunderstood illness – and as necessary as it is for people, from the field of psychology to the general public, to read and understand them – they simply aren’t telling the whole story.

My eating disorder didn’t look like that, and it’s been difficult to find stories that more closely resemble my own. My eating disorder was private and lonely. My rapid weight loss raised a few concerned eyebrows and flippant comments, but only one intervention. My doctor didn’t offer anything to me except a nutritionist and an SSRI prescription – oh, and the dreaded diagnosis of EDNOS. My eating disorder wasn’t (yet) killing me. It wasn’t making strangers stare at me. It looked entirely from the outside – so long as no one ever got a peek at my journals – like a diet.

And yet, my eating disorder was terrifying. And it was serious. And it mattered. Considering most people struggling with bulimia are of average weight, binge eating disorder is the most common eating disorder, most doctors hardly receive any training about eating disorders, and people are socially rewarded in our culture for dieting or weight loss, I have a suspicion that I’m not alone.

While some may argue that these bestsellers are raising important awareness about a growing problem, my question is: How beneficial is it if the scope of what the shoppers see is such a narrow picture of eating disorder experiences? How concerning is it that many write these memoirs without realizing how critical it is to share their story responsibly – in ways that doesn’t invite comparisons of “not sick enough to count” or with triggering images and instructive behaviors?

Because here is what happens when the only eating disorder stories that we hear are the ones that fit the aforementioned description: We use them as examples to hold our own disorders up to. We use them to judge and determine what is and isn’t “really sick.” We start to trust that these narratives represent “real” eating disorders, and that experiences that fall outside of these confines just don’t count.

And that’s dangerous.

It’s dangerous for the men and the boys who are struggling when they’re looking in the mirror. It’s dangerous and invalidating for women and other people of color when eating disorders are chiefly looked at as a “white woman’s problem.” It’s dangerous for trans* folks whose body image battles are always lumped in as related to gender-related dysphoria.

It’s dangerous to every person who’s ever peered into the DSM for diagnostic criteria and thought, “Well, I don’t purge that much” or “I haven’t lost that much weight.” It’s dangerous to every person who’s ever thought that they must not be “that bad” just because they don’t see stars when they stand up or don’t have heart complications or haven’t been questioned about erosion by their dentist or don’t have to take a leave of absence from school or don’t ever see a therapist or don’t get admitted into residential treatment or don’t have to be fed through a tube.

As is every structure that exists to serve a hierarchy of power, when the landscape is primarily non-inclusive eating disorder stories, it’s dangerous to the marginalized. They say, “Your voices don’t matter. Your experiences aren’t important.” It’s dangerous to reality.

And something has to change.

So, with that in mind, I (in collaboration with NEDA) would like to collect and curate your eating disorder stories. We want to highlight recovery stories that challenge that dominant narrative formula. There are already some brave people out there sharing their stories, talking about how their ethnicity, gender identity, orientation, age, or religion have impacted their experience with an eating disorder, but as a field and community, we have still have so far to go. You are invited to join us.

We want all of it: your successes, your messes, your relapses, your questions. We want to hear from people of marginalized identities and from different parts of the world. We want to span the entire spectrum. We want to create a collection of stories that tells the whole truth so that we can present the world with what the reality of most eating disorders look like – because how can we truly address a problem if we don’t know what it looks like?

So if you have ever read an eating disorder memoir and felt misrepresented, underrepresented, or unrepresented, we want to hear from you. Submit your story now!

Interested in sharing your experiences as a step toward public enlightenment? For guidelines and to submit your stories, check out our submissions page here.

And for more on what I wish people understood about eating disorders, check out this video.