75 blood red vinyl discs in the J. David Goldin Collection do not belong to radio history in the strictest sense. These discs are music–well, Muzak. The Muzak company began in 1922 with a mission to challenge the radio market by selling wired-in music to businesses. As the wireless radio sounded in homes throughout the USA, Muzak provided a wired sound track to daily shopping, factory working, lobby waiting, and elevator riding. The majority of the tunes were engineered to be unimposing, instrumental versions of popular melodies, and the product was comfortably bland. This gave Muzak the reputation of eroding the quality of music in general and blatantly packaging music as wallpaper.

75 blood red vinyl discs in the J. David Goldin Collection do not belong to radio history in the strictest sense. These discs are music–well, Muzak. The Muzak company began in 1922 with a mission to challenge the radio market by selling wired-in music to businesses. As the wireless radio sounded in homes throughout the USA, Muzak provided a wired sound track to daily shopping, factory working, lobby waiting, and elevator riding. The majority of the tunes were engineered to be unimposing, instrumental versions of popular melodies, and the product was comfortably bland. This gave Muzak the reputation of eroding the quality of music in general and blatantly packaging music as wallpaper.

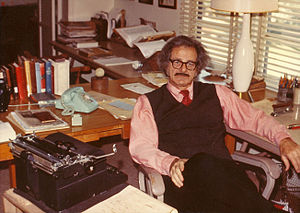

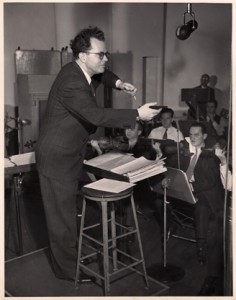

But that is not to say that the composers and arrangers employed by Muzak should be dismissed. Alexander Semmler is a good example. His disc entitled Alexander Semmler and his orchestra is among dozens and dozens of discs titled with a man’s name followed by “and his orchestra.” He included an original piece called “Drifting Melody” in his Muzak session which exposes him as more than an arranger. But the music does not stand out (it’s not supposed to). The instrumentation was for violins, piano, and flute, a typical Muzak instrumentation meant to avoid “harsh” timbres. This music, however, becomes important when we understand more about Semmler.

Semmler was a very active composer and conductor at CBS in the late 1930s and throughout the 1940s. He mainly wrote and conducted music for radio dramas. It was normal for radio drama music to be unobtrusive; depending on the skill of the radio writer, the music could be an integral part of the drama and could go beyond the merely incidental. He worked with many talented radio writers including Nila Mack of Let’s Pretend, Orson Welles, and Norman Corwin the “Poet Laureate of Radio.”

Semmler was a very active composer and conductor at CBS in the late 1930s and throughout the 1940s. He mainly wrote and conducted music for radio dramas. It was normal for radio drama music to be unobtrusive; depending on the skill of the radio writer, the music could be an integral part of the drama and could go beyond the merely incidental. He worked with many talented radio writers including Nila Mack of Let’s Pretend, Orson Welles, and Norman Corwin the “Poet Laureate of Radio.”

Corwin especially appreciated Semmler’s music and made it prominent. Semmler’s score to Psalm for a Dark Year Corwin calls, “one of the finest ever composed for radio.” And in You Can Dream, Inc., Corwin commissioned Concerto for Typewriter No. 1 in D. The two minute piece features an orchestral introduction followed by a dialogue between the orchestra and typewriter. The orchestra imitates the rhythm of the typing, and after a minute there is a silence. The female typist sighs, returns the carriage, and the concerto continues. The sounds of the typewriter were common enough that they could communicate the mood of the person at the machine, and Semmler used this to add drama to this little composition. To end the piece, the tension builds musically with speed and volume in the orchestra while the typist seems to be in a whirlwind of inspiration, holding her breathe until the last letter is struck. The result is a jumbled, finger fatiguing coda.

Concerto for Typewriter No. 1 in D is a little gem that has fallen prey to the “ghastly impermanence” of radio. In fact, the whole field of historical American radio drama has yet to be treated seriously as a field for scholarship. Perhaps musicologists can start a new trend.

…so hidden away in a stack of 10,000 records is a disc titled Alexander Semmler and his orchestra. The music does not invite serious analysis, and the word “Muzak” on the label stereotypes the content. But with a little digging the disc becomes a one of a kind document about a great American radio composer. Could it be that every disc in this collection has something valuable about it waiting for discovery? Lets find out!

Troy Cummings, guest contributor