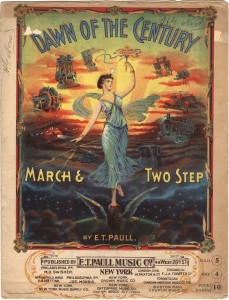

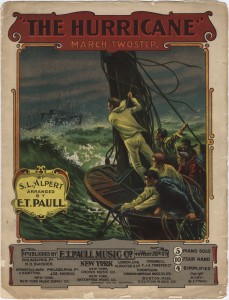

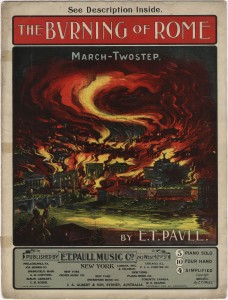

Edward Taylor Paull’s music is pretty much universally panned as mediocre. Think of him as the Rebecca Black of his generation. So why are his self-published pieces of sheet music so collectable? It’s the beauty of their covers. He used an expensive five-color lithograph process which led to covers that were meant to grab the eyes and wallets. We have many of his pieces in the Popular American Sheet music collection which I think you will agree are magnificent.

Tag Archives: music

Native Song

Staff Pick: Missouri Folk Songs sung by Loman D. Cansler (Folkways Records: FH5324, 1959)

Part regional history, and part family heirloom, Missouri Folk Songs is a rare collection of our state’s native songs, performed by Dallas County, Missouri-native Loman D. Cansler (1924-1992)[1]. Continue reading

She’s Like Elvis, But Hotter

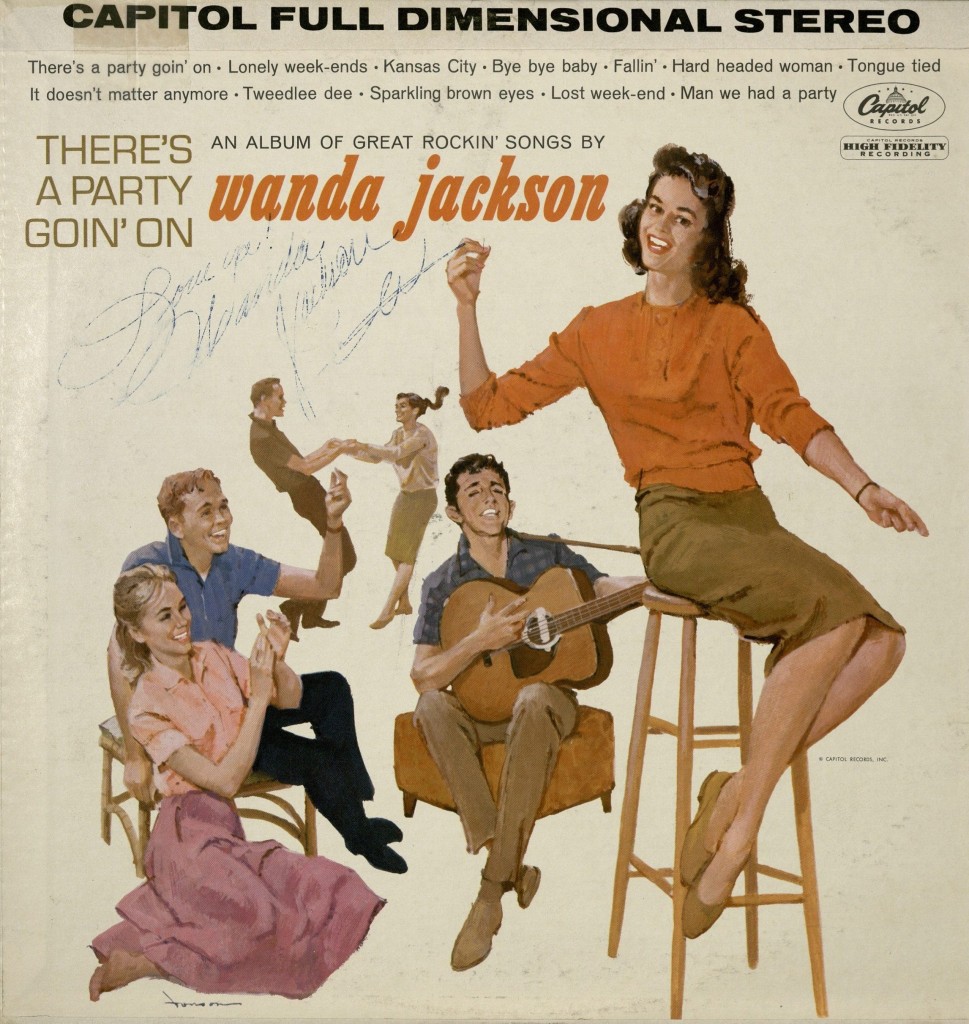

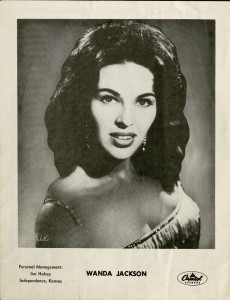

Staff Pick: There’s A Party Going On, Wanda Jackson (Capitol, 1961)

Although she’s still referred to as the “Queen of Rock n’ Roll,” Wanda Jackson is not a household name. She’s an integral part of rockabilly and rock n’ roll history, however, and her gravely rasp and bold style is highly worth some overdue attention.

Born Wanda Lavonne Jackson in Maud, Oklahoma on October 20, 1937, Wanda’s father was the first to encourage her to play guitar, piano, and sing (he had also pursued a career as a country singer before the Depression). When she was a teenager, she performed regularly as a country artist on a local Oklahoma City radio show, where she was discovered by country superstar Hank Thompson. Wanda toured with Hank and his Brazos Valley Boys in 1954, and signed with Decca that same year.

During a 1955 package tour, Wanda was paired with the likes of Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly, and Elvis Presley. Wanda and Elvis dated briefly, but remained friends for long after; she largely credits Elvis for encouraging her to pursue a career in rockabilly music. In addition to being one of the first (and few) women to sing rockabilly, Wanda was also one of the first women to add glamour to the scene with her pencil dresses, heels, glitter, and fringe.

In 1956, Wanda signed with Capitol Records, a relationship she would maintain into the early 70s. With Capitol, she cut her most successful singles, including “Fujiyama Mama,” “Mean Mean Man” and “Who Shot Sam,” which are still considered rockabilly classics today.

Her most popular single, “Let’s Have a Party,” released in 1960, was originally recorded by Elvis for the 1957 film Loving You. There’s a Party Going On, released on the heels of “Let’s Have a Party” in 1961, captures Wanda’s vibrant energy and raucous spirit. Must listens include Wanda’s rendition of “Kansas City,” and a silly number called “Tongue Tied,” a chronicle of Wanda’s lovestruck awkwardness. Her band on the album, dubbed The Party Timers, includes legendary country guitarist Roy Clark. To top it off, Marr’s copy of this album includes Wanda’s original signature on the cover with the note: Love you!

Although she gained fame for her rockabilly hits, Wanda eventually returned to her country roots, and even recorded gospel music in the 1970s after becoming a born-again Christian. Now 75, she continues to tour and record. In 2011 she put out the album, The Party Ain’t Over, which was produced by Jack White. Her latest album, Unfinished Business, released in 2012 and was produced by American singer-songwriter Justin Townes Earle. The Marr Sound Archives holds over a dozen of her records, including cuts from both the rockabilly and country genres.

[audio:http://info.umkc.edu/specialcollections/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/01-Tongue_Tied-Clip.mp3|titles=Tongue Tied by Wanda Jackson]Barbara Varanka, Graduate Assistant, Marr Sound Archives

The Passing of a “Genteel Englishwoman”

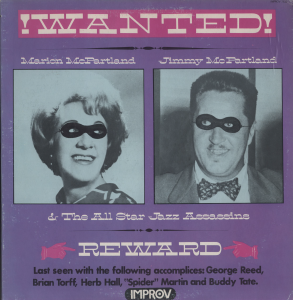

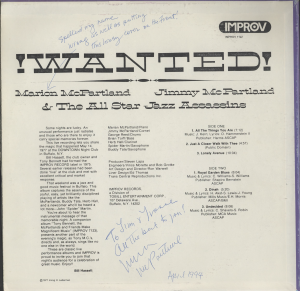

We mourn the recent passing of Marian McPartland, jazz legend and host of the popular radio show on NPR, “Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz.” Born in Windsor, England, March 20, 1918, McPartland moved to Chicago in 1946 with her American husband, Jimmy. She became a fixture of the American jazz scene, first as a pianist in the 1950s, and then in 1978 as the host of her radio show. McPartland was one of only three women featured in the iconographic 1958 photo A Great Day in Harlem, a b&w group portrait of 57 notable jazz musicians photographed in front of a brownstone in Harlem, New York City by freelance photographer Art Kane, for Esquire Magazine (McPartland is on the front row, standing next to KC native and jazz pianist great, Mary Lou Williams.)

The Marr Sound Archives on the ground floor of Miller Nichols Library houses many recordings of McPartland. Check out our library catalog!

One favorite LP located in Marr is the 1977 recording on the Improv label: Marian and Jimmy McPartland and the All Star Jazz Assassins. Our copy features McPartland’s signature with additional narrative: “Spelled my name wrong as well as putting this lousy cover on the front!” You judge the cover for yourself!

Always experimental, when McPartland turned 80, she said “I’ve become a bit more — reckless, maybe. I’m getting to the point where I can smash down a chord and not know what it’s going to be, and make it work. And though I’ll never swing like Mary Lou Williams, I’m better at it than I used to be”–Terry Teachout, The New York Times, March 15, 1998.

McPartland passed away at the age of 95 on Aug. 20, 2013 at her home in Port Washington, N.Y.

~ Wendy Sistrunk, Head, Special Formats Metadata & Cataloging Dept., UMKC

Tex Owens: A case of mistaken identity?

As he is often referred to as the “Original  Texas Ranger,” it is commonly assumed that Tex Owens was an original member of the Texas Rangers, a western music group from the Kansas City-based radio station KMBC who became nationally recognized stars in the 1930s and 1940s.

Texas Ranger,” it is commonly assumed that Tex Owens was an original member of the Texas Rangers, a western music group from the Kansas City-based radio station KMBC who became nationally recognized stars in the 1930s and 1940s.

Understandably, it is easy to make that assumption when programs featuring the Texas Rangers such as “Life on Red Horse Ranch” featured Tex and his serenading of the “dogies” in nearly every episode. However, the Texas Rangers radio program, hosted by Hiram Higsby, never referred to Tex as a member but rather as a special guest. So what was it? Was Tex Owens the “Original Texas Ranger” or was he an associated act? Well, it depends on whom you ask.

Thankfully, due to a recent discovery in the LaBudde Special Collections here at UMKC, we can learn more about this question. Tex Owens, at least according to the Texas Rangers, was not a member of the group, but rather a popular musical affiliate. In January 1939, Governor James Allred of Texas planned to honor the members of the group–Tex Owens included–by declaring them Honorary Texas Rangers during a radio broadcast. This inclusion of Tex in the honor was not well-received by the Rangers and their jug and bass player Clarence Hartman sent an internal memo on behalf of the group to Stuart Eggleston, a member of Arthur B. Church’s senior staff, expressing their frustrations. Hartman opened the letter by stating that the Texas Rangers were disappointed that the honor was being shared by “someone whom [they considered] entirely outside [of their] group.” He also added that they, and the listeners, felt that Tex hadn’t “added anything” to the broadcasts, and that it was unfair to the other Rangers to promote him as a member of the group.

The next paragraph is particularly interesting, as Hartman claimed that on a number of occasions Tex made damaging statements about the Rangers to people outside of the group. On one occasion, Hartman stated that following a poor radio performance by Tex he overheard Tex telling two other employees that none of the Rangers would help him improve, an allegation which Hartman flatly denied. Lastly, Hartman clarified Tex’s member status by adding that the “old timers” at the station asserted that Tex “never, at any time, has been a member of the Texas Ranger group.” Tex himself made that claim to membership, according to Hartman, and any doubts of these facts should be conferred with Gomer Cool, the Rangers’ violinist who had been a long-time employee of KMBC.

How was this letter received, you ask? Luckily, we know that too. We can assume that in the business of radio, Arthur B. Church made his decisions based on what would attract the most sponsors and listeners, and as the honoring of the Rangers was surely broadcasted over a vast audience, the matter had to be handled delicately. Church’s remark, penciled at the bottom of Hartman’s memo, demonstrated an unwillingness to ruffle feathers, as well as an assurance that all decisions were going to be made for the benefit of the station regardless of the feelings of individual members:

Stu — It is my feeling that the group has nothing to lose by having Tex included, and it means as much to him as to any person in the group; and even more important[ly] — is valuable to KMBC. — ABC, 1/10/39

Christina Tomlinson, KMBC Project staff/History (MA) student

The 75th anniversary of Raymond Scott’s music

2012 marks the 75th anniversary of the public introduction of Raymond Scott’s music! Find out more about events surrounding this occasion at the Raymond Scott Archives blog. And don’t forget to check out what your very own LaBudde Special Collections has to offer in the Raymond Scott Collection donated by Raymond’s widow, Mitzi in 1993.

2012 marks the 75th anniversary of the public introduction of Raymond Scott’s music! Find out more about events surrounding this occasion at the Raymond Scott Archives blog. And don’t forget to check out what your very own LaBudde Special Collections has to offer in the Raymond Scott Collection donated by Raymond’s widow, Mitzi in 1993.

More memorable moments with the Brush Creek gang!

The Brush Creek Follies may have easily been classified as a western rural variety show, and to an extent, that’s exactly what it was. However, quite a few musicians featured on the Brush Creek Follies did not devote their musical abilities exclusively to hillbilly and western music. Such groups as the Midland Minstrels (pictured right), Harvest Hands, Judy Allen, and the Payne Sisters all performed songs that appealed to novelty and popular music crowds. These musicians were incredibly good, especially the multi-talented Charlie Pryor, originally a member of the Midland Minstrels and later affiliated with the Tune Chasers. Listen to an excerpt displaying the versatility of the musicians on the Brush Creek Follies.[audio:http://info.umkc.edu/specialcollections/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/2012-02-13_BrushCreek2_Church_kmbc-785.mp3|titles=Whatcha know Joe]

The Brush Creek Follies may have easily been classified as a western rural variety show, and to an extent, that’s exactly what it was. However, quite a few musicians featured on the Brush Creek Follies did not devote their musical abilities exclusively to hillbilly and western music. Such groups as the Midland Minstrels (pictured right), Harvest Hands, Judy Allen, and the Payne Sisters all performed songs that appealed to novelty and popular music crowds. These musicians were incredibly good, especially the multi-talented Charlie Pryor, originally a member of the Midland Minstrels and later affiliated with the Tune Chasers. Listen to an excerpt displaying the versatility of the musicians on the Brush Creek Follies.[audio:http://info.umkc.edu/specialcollections/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/2012-02-13_BrushCreek2_Church_kmbc-785.mp3|titles=Whatcha know Joe]

In addition to the great musical performances, the show presented familiarity to its listeners with the use of catchphrases by certain cast members. Here are just a few that have been burned into my mind after many hours of listening:

“Well for gosh sakes!” — Scrappy O’Brien, Kenny Carlson’s ventriloquist dummy, would always follow this catchphrase with a laugh and the occasional “Aw, shucks.” The “gosh” part of this catchphrase could last a good five seconds.

“Now cut it out, will ya?!” and “No foolin’…” — “Radio’s original rube” Hiram Higsby always had something clever to say or do during the show. Playing the part of the emcee for the Brush Creek Follies, he also announced most of the performances and was a regular part of the comedy routines, which often included these two catchphrases.

The laugh of Rube Wintersuckle — Think of what it would sound like if while driving, you rolled over a series of bumps while laughing. This is exactly what Rube Wintersuckle’s trademark laugh sounded like. Playing a red-headed hillbilly, Wintersuckle tended to come off as brainless because of his appearance and demeanor, but in the end, he always had the last laugh (no pun intended).

“Oh man…” and “Ain’t you hear?” — Probably the most discriminating and cringe-worthy of all of the Brush Creek catchphrases would be George Washington White and his black-faced comedy routine.

“Timber, timber, timber, timber!” — Similar to the way the Three Stooges harmoniously sang their hellos, Rocky and Rusty always introduced their songs with their own theme song.

“Uncle Charlie!” — Little Mary, a latecomer to the 1941 season, always brought about big laughs from the audience with her high-pitched voice, and we may never know why or what she looked like.

Gabby Tuttle, KMBC Project staff/Liberal Arts (BA) student

For more photos, information, and audio clips on the Brush Creek Follies, visit the Brush Creek Follies web exhibit.

Memorable moments with the Brush Creek gang

Come on everybody, get ready to go, this is the Brush Creek Follies show! There’s singing and dancing and fun galore, and maybe if you whoop and holler we will do some more! Saturday night in Kansas City was a night of comedy, singing, dancing, and pure entertainment for the public provided by the local variety show, the Brush Creek Follies. Similar to the Grand Ole Opry, this live radio program showcased western-style musicians, comedians, and the occasional special guest. Thanks to the Arthur B. Church collection available in the Marr Sound Archives, you can have access to the shows that aired in 1941 as well as a select few others.

The 1941 season of BCF was smack dab in the middle of World War II, but you could hardly tell because of the excitement the show brought every Saturday night. Each week, BCF had a theme, which gave the performers a central focus for their weekly material. Some themes were targeted towards a certain population of listeners, such as “Irish night”, “Kid’s night,” or “Couple’s night.” Other themed nights were celebratory, such as the 3rd anniversary of Colorado Pete, a yodeling cowboy. My personal favorite, “Beaver’s night,” entailed all the men not shaving throughout the week, and a contest was even held to find the longest whiskers in the audience. What made the show successful were the performers, who all had extremely devoted fans. Kit and Kay, twin singing cowgirls, were especially popular and often received flowers and gifts from audience members.

The show’s regular performers appealed to all ages: a favorite for the kids was ventriloquist Kenny Carlson and his dummy, Scrappy O’Brien; the older generation could listen to the “Remember Time” segment, in which singing couple, Smokey Parker and Penny Lynn would sing “oldies but goodies;” and you could hear young girls literally swooning over the singing cowboy groups, like the Oklahoma Wranglers and Rocky and Rusty. Of all the acts that I had heard, nothing was quite as original and still mysterious as Little Mary’s comedy skit, often done with BCF co-host, Charlie Napier. What makes Little Mary mysterious is that I haven’t figured out just what she is. I have created this idea that she is either a man dressed up like a little girl or a puppet. All the same, her high-pitched voice and constant antagonizing Napier is very amusing. Click here to listen to an excerpt from the show.[audio:http://info.umkc.edu/specialcollections/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/2012-01-24_BrushCreek1_Church_kmbc-757.mp3|titles=Kenny and Scrappy]

Coming up in the second installment of this two-part Brush Creek Follies special, we will look at some super-talented musicians and the catchphrases that I couldn’t forget if I tried.

Gabby Tuttle, KMBC Project staff/Liberal Arts (BA) student

For more photos, information, and audio clips on the Brush Creek Follies, visit the Brush Creek Follies web exhibit.

Chuck Haddix to speak about “Brush Creek follies” tonight on KCUR

Tune into KCUR 89.3 FM KC Currents, tonight at 8 p.m., to hear Alex Smith speaking with our own Chuck Haddix about The Brush Creek Follies and check out this wonderful digital exhibit by the folks in special collections.

Enjoy!

Muzak, radio

75 blood red vinyl discs in the J. David Goldin Collection do not belong to radio history in the strictest sense. These discs are music–well, Muzak. The Muzak company began in 1922 with a mission to challenge the radio market by selling wired-in music to businesses. As the wireless radio sounded in homes throughout the USA, Muzak provided a wired sound track to daily shopping, factory working, lobby waiting, and elevator riding. The majority of the tunes were engineered to be unimposing, instrumental versions of popular melodies, and the product was comfortably bland. This gave Muzak the reputation of eroding the quality of music in general and blatantly packaging music as wallpaper.

75 blood red vinyl discs in the J. David Goldin Collection do not belong to radio history in the strictest sense. These discs are music–well, Muzak. The Muzak company began in 1922 with a mission to challenge the radio market by selling wired-in music to businesses. As the wireless radio sounded in homes throughout the USA, Muzak provided a wired sound track to daily shopping, factory working, lobby waiting, and elevator riding. The majority of the tunes were engineered to be unimposing, instrumental versions of popular melodies, and the product was comfortably bland. This gave Muzak the reputation of eroding the quality of music in general and blatantly packaging music as wallpaper.

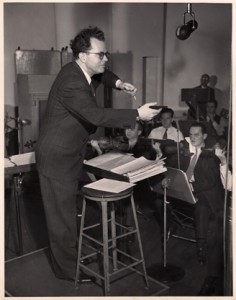

But that is not to say that the composers and arrangers employed by Muzak should be dismissed. Alexander Semmler is a good example. His disc entitled Alexander Semmler and his orchestra is among dozens and dozens of discs titled with a man’s name followed by “and his orchestra.” He included an original piece called “Drifting Melody” in his Muzak session which exposes him as more than an arranger. But the music does not stand out (it’s not supposed to). The instrumentation was for violins, piano, and flute, a typical Muzak instrumentation meant to avoid “harsh” timbres. This music, however, becomes important when we understand more about Semmler.

Semmler was a very active composer and conductor at CBS in the late 1930s and throughout the 1940s. He mainly wrote and conducted music for radio dramas. It was normal for radio drama music to be unobtrusive; depending on the skill of the radio writer, the music could be an integral part of the drama and could go beyond the merely incidental. He worked with many talented radio writers including Nila Mack of Let’s Pretend, Orson Welles, and Norman Corwin the “Poet Laureate of Radio.”

Semmler was a very active composer and conductor at CBS in the late 1930s and throughout the 1940s. He mainly wrote and conducted music for radio dramas. It was normal for radio drama music to be unobtrusive; depending on the skill of the radio writer, the music could be an integral part of the drama and could go beyond the merely incidental. He worked with many talented radio writers including Nila Mack of Let’s Pretend, Orson Welles, and Norman Corwin the “Poet Laureate of Radio.”

Corwin especially appreciated Semmler’s music and made it prominent. Semmler’s score to Psalm for a Dark Year Corwin calls, “one of the finest ever composed for radio.” And in You Can Dream, Inc., Corwin commissioned Concerto for Typewriter No. 1 in D. The two minute piece features an orchestral introduction followed by a dialogue between the orchestra and typewriter. The orchestra imitates the rhythm of the typing, and after a minute there is a silence. The female typist sighs, returns the carriage, and the concerto continues. The sounds of the typewriter were common enough that they could communicate the mood of the person at the machine, and Semmler used this to add drama to this little composition. To end the piece, the tension builds musically with speed and volume in the orchestra while the typist seems to be in a whirlwind of inspiration, holding her breathe until the last letter is struck. The result is a jumbled, finger fatiguing coda.

Concerto for Typewriter No. 1 in D is a little gem that has fallen prey to the “ghastly impermanence” of radio. In fact, the whole field of historical American radio drama has yet to be treated seriously as a field for scholarship. Perhaps musicologists can start a new trend.

…so hidden away in a stack of 10,000 records is a disc titled Alexander Semmler and his orchestra. The music does not invite serious analysis, and the word “Muzak” on the label stereotypes the content. But with a little digging the disc becomes a one of a kind document about a great American radio composer. Could it be that every disc in this collection has something valuable about it waiting for discovery? Lets find out!

Troy Cummings, guest contributor