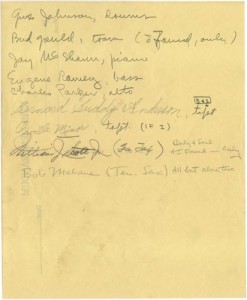

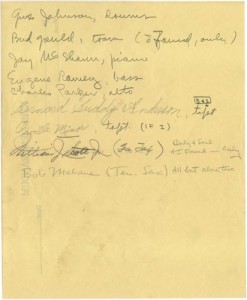

Sign-in sheet for KFBI recording date

The Higginson Collection consists of two handwritten documents of great value and historic significance. These one-of-a-kind documents survived from the first recording dates for Kansas City jazz pianist Jay McShann and his band, which included alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, then only 20 years old. The recording session happened between November 30 and December 2, 1940, and was supervised by Fred Higginson of radio station KFBI in Wichita, Kansas.

The first document is a sign-in sheet containing the signatures and instrument played of each band member, and represents one of the earliest known signatures of Charlie Parker.

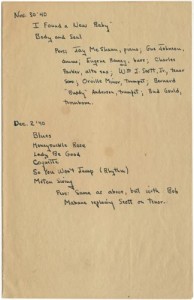

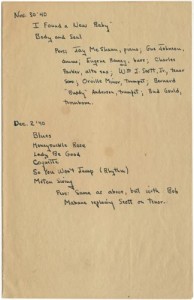

The second document contains the song list and corresponding band personnel for the two days of recording, November 30 and December 2, providing primary source information about the discographical details of the session.

Discography sheet for KFBI recording date

Chuck Haddix explains the significance of the session, especially as a conduit of Parker’s musical development, in his book Kansas City Jazz: From Ragtime to Bebop – A History:

As Decca [Records] released the Kansas City Jazz album in the spring of 1941, the last great big band to come out of Kansas City, the Jay McShann band, rose nationally, boosted by good fortune and a hit recording. After closing at Fairyland [Park in Kansas City] in September 1940, McShann returned to the Century Room and further refined the band’s personnel, replacing alto saxophonist Earl Jackson with John Jackson. Slim and pensive, Jackson rivaled [Charlie “Bird”] Parker as a soloist. While based at the Century Room, the McShann band toured regionally, ranging north to Des Moines, Iowa, east to Paducah, Kentucky, and west to Wichita, Kansas. During a Thanksgiving weekend engagement in Wichita, a brash young college student and jazz fan, Fred Higginson, invited McShann and other band members for a couple of after-hours sessions at radio station KFBI, named after Kansas Farmer and Business. KFBI traced its lineage back to Dr. Brinkley, the goat gland doctor. McShann, figuring the band could use a little experience in the studio before the pending Decca sessions, took Higginson up on the offer.

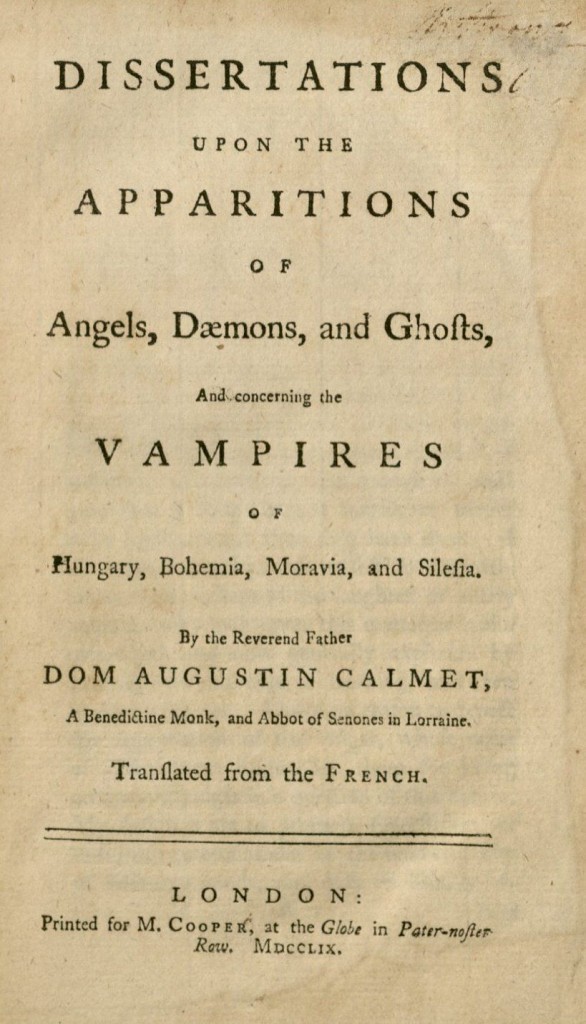

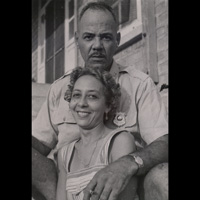

Orville Minor, Bob Mabane, Gus Johnson, Bernard Anderson, Charlie Parker, Gene Ramey, Jay McShann; recording date for radio station KFBI; Witchita, Kansas; c. November 30 – December 2, 1940 (Jay McShann Collection)

The station’s engineer recorded the sessions to acetate discs, capturing the unit jamming on the standards “I Found a New Baby,” “Body and Soul,” “Moten’s Swing,” “Coquette,” “Lady Be Good,” “Honeysuckle Rose,” and on their theme song, listed as an untitled blues. While the band struggled to find its niche in the Kansas City jazz tradition, Charlie Parker had already transcended previous jazz conventions. [McShann bassist] Gene Ramey felt band members could not fully appreciate Parker’s techniques and ideas. “When I look back, it seems to me that Bird was at the time so advanced in jazz that I do not think we realized to what degree his ideas had become perfected,” Ramey observed. “For instance, we used to jam ‘Cherokee.’ Bird had his own way of starting from a chord in B natural and B flat; then he would run a cycle against that; and, probably, it would only be two or three bars before we got to the channel [middle part] that he would come back to the basic changes. In those days, we used to call it ‘running out of key.’ Bird used to sit and try to tell us what he was doing. I am sure that at that time nobody else in the band could play, for example, even the channel to ‘Cherokee.’ So Bird used to play a series of ‘Tea for Two’ phrases against the channel, and, since this was a melody that could easily be remembered, it gave the guys something to play during those bars.”

Parker’s innovative technique and wealth of ideas are evident in his solos on “Body and Soul” and “Moten’s Swing.” Parker maintains the ballad tempo of “Body and Soul” while running in and out of key. Taking a cue from Parker, the band and Buddy Anderson switch to double time, before returning to the ballad tempo in the last eight bars of the out chorus. After the piano introduction to “Moten’s Swing,” the band launches into the familiar riff pattern. Parker follows with a confident, articulate solo, highlighted by triplets in the second eight-bar section, and triplet flourishes toward the end of the bridge, first stating, on record, his musical signature. Parker had matured into a fully realized improviser, already pioneering a new musical style critics later labeled bebop. He soon had company.

Like this:

Like Loading...