Dec 14

8

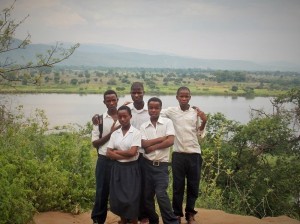

St. Michael’s students pose on the school campus, overlooking the Shire River, before a debate competition against a neighboring school

For the past year and a half, I have been living and working in Chikwawa, Malawi as a Peace Corps volunteer. My primary project is teaching English and mathematics, although I also facilitate several after school clubs (Debate, English, and Girls club) and lead computer/Internet literacy workshops. I spend most of my days at St. Michael’s Community Day Secondary School (CDSS). CDSS’s, at the bottom tier of the Malawian education system, receive little – if any – government funding and are characterized by a lack of resources and an overabundance of students. At St. Michael’s CDSS, a school with roughly four hundred students and four usable classrooms, tuition is a mere 10 dollars a term (totaling thirty dollars per year). This amount places a serious financial burden on my students and their families. In fact, most Malawian children do not complete secondary school. Females, in particular, face enormous obstacles in completing their education with only 5 percent eventually receiving their Malawi School Certificate (the equivalent of a high school diploma).

These challenges are real and, frankly, pretty difficult to confront day in and day out. Nonetheless, the ability to understand these challenges in their particular context has enabled me to be a better volunteer; I recognize my place in the complex system I am a part of and am able to shape my work accordingly. The perspective, theoretical knowledge, and practical skills I gained from studying sociology (and Spanish!) at UMKC have helped me integrate into my community and have continuously informed my work. Always at the forefront of my mind, whether I’m teaching a class or helping girls sew sanitary pads, is the potential for unintended and/or harmful consequences of seemingly beneficial actions, a lesson instilled me in by Lauriston Sharp’s classic “Steel Axes for Stone-Age Australians” covered in a cultural anthropology class. I could go on and on citing specifics, but suffice it to say that classes at UMKC on social change, statistics, theory, structured inequalities – they have all helped me make sense of this place that is so different from my home. Not only does my work feel informed, it feels meaningful. I am able to appreciate the nuances of Malawian culture and society from a unique standpoint as a result of my studies in sociology at UMKC. For that, ndathokoza kwa bas (I am very grateful) to all of the wonderful professors and support staff at UMKC. Zabwino zonse (all the best)!

Thank you,

Isabella