And the legacy of Edgar Snow

The biennial Edgar Snow Symposium returned to Kansas City with an array of events celebrating the 36-year-old partnership between the Kansas City-based Edgar Snow Memorial Foundation and the Beijing-based China Society for People’s Friendship Studies.

The Edgar Snow Memorial Foundation was founded in 1974 by Mary Clark Dimond and her husband E. Grey Dimond, M.D. E. Grey Dimond was a founder of the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine and its innovative six-year medical degree program. The Dimonds were citizens of the world, and high among their global concerns was expanding and improving U.S.-China relations. Their former home is now a special gathering place for community, regional, national and international scholars. Diastole Scholars’ Center is located on the UMKC Health Sciences Campus on Hospital Hill.

Nancy Hill, Diastole executive director, is president of the Edgar Snow Memorial Foundation, and coordinated the symposium that brought international scholars, artists, civic, education, business and community leaders from the U.S. and China together to share information and ideas. The gala on Oct. 5 featured a representative for Chinese Ambassador to the United States Cui Tiankai. Kansas Governor Jeff Colyer gave a toast to the continuation of a strong relationship.

“We are in a new era of Chinese American relationships,” Colyer said. “Let’s embrace the discussion. Let’s move forward. All of that relates to the Edgar Snow Foundation because he opened those doors.”

“We are in a new era of Chinese American relationships,” Colyer said. “Let’s embrace the discussion. Let’s move forward. All of that relates to the Edgar Snow Foundation because he opened those doors.”

University of Missouri System President Mun Choi echoed Colyer’s sentiments as he greeted attendees on behalf of the four universities that are part of the UM System.

“Over the years, the symposiums have brought our two countries together,” Choi said.

Recognition of Sister City delegations from Yan’an and Xi’an was made by Kansas City Mayor Pro Tem Scott Wagner. He called Edgar Snow’s work “a relationship that endures.”

Recognition of Sister City delegations from Yan’an and Xi’an was made by Kansas City Mayor Pro Tem Scott Wagner. He called Edgar Snow’s work “a relationship that endures.”

“Relationships are built by everyone who interacts at all levels,” Wagner said. “Part of the reason we have the good relationship we have with China is because of the UMKC Enactus students at UMKC. When they go to China, they tell our story. The students show people in China what this region and city are all about.”

Acting PRC Consul General Liu Jun talked about Snow’s courageous spirit.

“Snow made it known, through his writing, that China is a proud nation, and that we share more commonalities,” Jun said.

This year’s Edgar Snow Symposium was the first for UMKC Chancellor C. Mauli Agrawal. He is looking forward to seeing what will come out of the meetings.

“I am proud that connection has continued to bring special relationships to UMKC and to Kansas City for over 40 years. I am proud of the work we are doing to advance this special relationship and to continue the lasting legacy of Edgar Snow.”

“I am proud that connection has continued to bring special relationships to UMKC and to Kansas City for over 40 years. I am proud of the work we are doing to advance this special relationship and to continue the lasting legacy of Edgar Snow.”

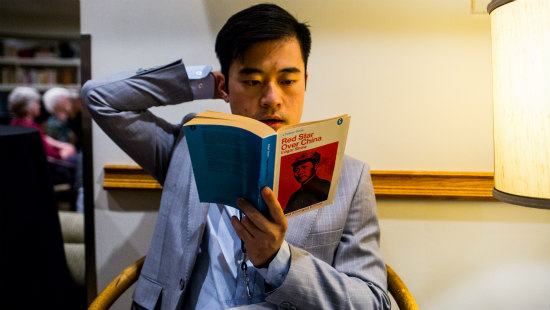

Edgar Snow

Edgar Snow was born in Kansas City, Missouri. He was an American journalist known for his books and writings on Communism in China, including the book “Red Star Over China.” He was the first Western journalist to interview major Chinese officials, including Mao Zedong.

Snow met many influential people through the years. In 1970, Snow and his wife made a final trip to China when Mao Zedong informed Snow that he would welcome President Richard Nixon to China either as a tourist or in his official capacity as President of the United States.

Snow met many influential people through the years. In 1970, Snow and his wife made a final trip to China when Mao Zedong informed Snow that he would welcome President Richard Nixon to China either as a tourist or in his official capacity as President of the United States.

Snow died before Nixon’s trip to China in 1972, but former United States Ambassador to China Nicholas Platt was on that inaugural trip. At the Friday night gala, Platt presented the Edgar Snow Symposium Gala Banquet keynote lecture, “China-US Relations: Then and Now.” While Platt showed home movie clips and photos from the 1972 trip to China, he talked about the lasting impact of those trips.

“The Nixon visit to China in 1972 and the opening of resident diplomatic offices in Beijing and Washington 14 months later were two related but distinctly separate events that shaped the start and future of US-PRC relations. The first was a geo-strategic stroke that altered the global balance of power. The second was a tactical arrangement that created the logistics for the huge people to people dynamic which our relationship later became. I was fortunate to be present at both and to play a small operational role.”

Platt read a vignette from his book, “China Boys: How U.S. Relations with the PRC Began and Grew: A Personal Memoir.” The reading was about conversations between President Nixon, Secretary of State William P. Rogers and H. R. Haldemann. Others involved were Assistant Secretary Marshall Green and John Holdridge from National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger’s staff. Platt said the leading Asian experts in the U.S. government were preparing to leave on a tour of Asian capitals to explain what Nixon had accomplished in China the week before. It was at this time when Platt was introduced as one of the new China specialists in the State Department.

Platt read a vignette from his book, “China Boys: How U.S. Relations with the PRC Began and Grew: A Personal Memoir.” The reading was about conversations between President Nixon, Secretary of State William P. Rogers and H. R. Haldemann. Others involved were Assistant Secretary Marshall Green and John Holdridge from National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger’s staff. Platt said the leading Asian experts in the U.S. government were preparing to leave on a tour of Asian capitals to explain what Nixon had accomplished in China the week before. It was at this time when Platt was introduced as one of the new China specialists in the State Department.

“I told Nixon that I had spent 10 years preparing for this trip and was grateful to him for making it happen.” Platt said Nixon’s reply was, “Well, you China boys are going to have a lot more to do from now on.”

China-US Relations: Then and Now

Platt said the opening of U.S. China relations in 1972 was based primarily on balance of power considerations. He said Mao and Zhou needed a relationship with the United States to increase China’s weight against a threatening Soviet Union on its borders. Platt said Nixon and Kissinger calculated that a relationship with China would push the Soviet Union off balance and move it toward supporting U.S. policy goals such as arms control and extrication from Vietnam.

“The leaders of Washington and Beijing managed the balance of power mechanism personally, in a relationship that resembled a single line, hand cranked tactical field telephone line with Kissinger at one end and Zhou Enlai at the other. It was a subtle process that could be handled no other way. It worked.”

Platt said the prospect of a positive relationship threw the Soviets off balance, enhanced China’s confidence in its military confrontation with Moscow and enabled the U.S. to develop, for the first time since Japan annexed Manchuria in the 1930s, constructive relations with both Japan and China. East Asia stabilized and facilitated unprecedented decades of explosive economic growth. Pressure by Kissinger, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan led to the collapse of the USSR in 1989.

“With the Soviet Union gone, the U.S. emerged as the sole superpower,” Platt said. “Resident offices in place after 1973 enabled the peoples of China and the U.S. to interact for the first time since 1949 when the Communists took power. Our relationship began to develop in ways none of us, including the great balancers, could foresee.”

Platt said that was the beginning of a true international relationship that operated people to people rather than government to government.

“Over the years, aided by the forces of globalization, professionals on both sides fastened together the ‘nuts and bolts’ creating an economic imperative that replaced the original strategic rationale that had collapsed,” Platt said. “China’s rapid economic rise in the decades that followed brought the balance of power concept back into operation. For the first time since the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was power to balance.”

Today travel from the U.S. or China, headed in either direction, is commonplace. He said travel is motivated by curiosity and self-interest, study, purchasing, investing, tourism and more.

“The governments, at least up until now, have encouraged the interaction between people, companies and institutions,” Platt said. “The huge interdependent relationship created has been the ballast for our relationship, keeping it from being blown off course by political winds, including such events as Tiananmen, the bombing of the PRC Embassy in Belgrade and the spy plane downing over Hainan Island.”

But we are now confronted with puzzling contradictions, Platt said.

“The media and think tanks, which spend little time analyzing the giant private interactions, exchange frowns about worsening bilateral relations, while people actually working the relationship have a hard time finding a seat on a plane in either direction. Policy shifts on both sides now threaten interdependence. The looming conflict threatens our trade. China thinks our new tariffs are designed to stunt its growth. We accuse China of getting ahead by stealing our technology. National security officials on both sides regard each other as adversaries. I am frequently asked if the relationship that has changed and moved the world for almost 50 years, can last. I believe so. Is conflict inevitable? I believe not. China is too big to contain, the relationship too complex to dismantle.”

Platt said sovereign states now measure the vulnerability not only to one another but increasingly to forces beyond their control. He said national planners must deal with the global threats of climate change, terrorism, radical Islam, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and medical plagues, whether they want to or not.

“We want the two economies and societies to be so closely connected that resorting to force is no longer even thinkable, much less doable.”

Platt said younger generations in both countries agree with him.

“The most recent polls indicate that they share innovative, entrepreneurial urges and are more favorably inclined toward each other than their elders,” Platt said. “Let’s give them time to decide.”

Additional featured events of the symposium included a discussion with Major Garrett, author, podcast host and CBS chief White House correspondent. He served on the Edgar Snow Symposium’s journalism panel, “Practicing Journalism in an Era of Globalization.”

Additional featured events of the symposium included a discussion with Major Garrett, author, podcast host and CBS chief White House correspondent. He served on the Edgar Snow Symposium’s journalism panel, “Practicing Journalism in an Era of Globalization.”

Garrett, who previously traveled to China as a reporter during the presidencies of Obama and Trump, responded to research presented by his fellow panelists, Professor Ernest Zhang and Professor Yong Volz, both of the University of Missouri School of Journalism; and Professor Wenxiang Gong of Peking University. To take a quote from Gong, “diversity in perception is constant.” The idea that each journalist and every one of their readers perceives a story differently was a theme throughout the presentations.

Garrett, who previously traveled to China as a reporter during the presidencies of Obama and Trump, responded to research presented by his fellow panelists, Professor Ernest Zhang and Professor Yong Volz, both of the University of Missouri School of Journalism; and Professor Wenxiang Gong of Peking University. To take a quote from Gong, “diversity in perception is constant.” The idea that each journalist and every one of their readers perceives a story differently was a theme throughout the presentations.

Moderated by Larson Powell, professor at the UMKC College of Arts and Sciences, panelists touched on research ranging from the effect of socioeconomic factors on reporters in China during the early 20th century to the consumption of knowledge in today’s media landscape.