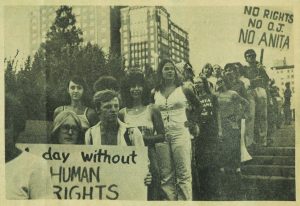

A New Era

Courtesy: New York Public Library Collections

On June 28, 1969, New York City police raided the Stonewall Inn. It was a raid like so many others, but on this night the inn’s patrons fought back by hurling rocks and bottles at the police. Over the next week two additional riots broke out in the neighborhood in protest.

The uprisings ignited a new atmosphere of militant gay liberation. A new generation of activist organizations emerged, including the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activist Alliance. Like the homophile movement, these new organizations sought to end discrimination against gays and lesbians. Unlike the homophile organizations, however, these advocates for “gay liberation” embraced much more aggressive tactics throughout the 1970s.

The Homophile Legacy

Courtesy: Gay and Lesbian Archive of Mid-America, University of Missouri-Kansas City

The rise of the gay liberation movement signaled the end of the homophile approach to gay rights. Though the 1969 NACHO meeting in Kansas City was the largest gathering of gay and lesbian activists to date, the conference took place just weeks after Stonewall. Its resolution creating a new Committee on Unity became lost in the flurry of new activism after the uprising. The conference’s meeting in San Francisco the following year became its last after younger activists demanded the organization expand its activities in order to connect with other social protests like the black power movement. The Phoenix Society also closed. Drew Shafer had exhausted all of his personal resources trying to keep the organization open.

Yet the militancy of the gay liberation movement would not have been possible without the groundwork laid by the homophile organizations. Their publications created the sense of national community that became realized after Stonewall, and many homophile activists contributed to the formation of gay liberation organizations. Even Kansas City’s Phoenix Society helped drive the rise of gay rights, distributing those publications that fostered new forms of activism. Although Stonewall became the emblem of change, it was organizations like the Phoenix Society that helped make history.