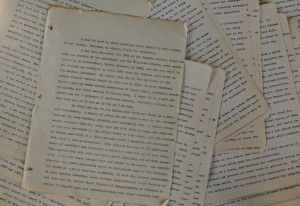

Frank C. Wornall’s memoir of the Wornall House is missing a few pages. Do the missing pages point to murder? (photo by bethanywearsphotography.com)

By Tony Lawson

When I first became familiar with the Wornall House history, one of the stories I heard was the tale of wounded Confederate soldiers recuperating in the second floor children’s bedroom. When the Union troops moved in and pushed Shelby’s troops back south they found the Wornall House being used as a regimental field hospital and the wounded Confederate soldiers inside. Local lore claims Union troops came into the bedroom and bludgeoned to death several wounded Confederate soldiers to make way for their own comrades wounded in the Battle of Westport. I was told that that plaster on the first floor ceilings had to be replaced from the blood that had oozed through from this event and that there still remained blood stains on the bedroom floor. Someone suggested we call in the police department forensics team to spray Luminol and whip out the black lights.

As I dig through the primary source material I have yet to find hard evidence that these murders occurred at the Wornall House. I did find that all the floorboards in the home were replaced sometime in the early twentieth century when plumbing, gas and electricity were installed. So, cancel that call for Luminol. There is nothing in Frank C. Wornall’s papers that explicitly tells this story, however, he does cryptically say that after the battle the Missouri State Militia officers had to use their sabers and other means to prevent the less disciplined troops of the Enrolled Missouri Militia “from killing them all.”

Frank apparently repeated this story several times in speeches that he gave over his long lifetime. In those cases, Inflection and tone would have been provided, however, in text form, that statement is perfectly vague. Does he mean some were killed and others were not? Or, does it mean, the EMM troops wanted to kill them all. It hints at the story of murder, but it is not conclusive of anything other than there was a confrontation between MSM officers and EMM troops over the handling of wounded Confederate prisoners at Wornall House. The confrontation nearly became violent at the least and at most it was the violent and cold blooded murder of wounded prisoners that has been obscured and forgotten by the general tumult of the war and its aftermath.

Additional evidence of this event is hinted at in the Wornall’s recounting of the battle. Both Frank and his father, John, mention the presence of seven dead Confederate soldiers on the southwest lawn. One of these was a colonel and a makeshift rail fence had been constructed around his body. There were surely lots of Confederate dead lying around the Wornall farm; why do they both mention those seven? Were these the Confederates bludgeoned to death in the bedroom?

(As an interesting side note, I discovered that the officer left in charge of the Confederate prisoners at Wornall House was Colonel John F. Richards who later headed up the firm of Richards and Conover Hardware Co. The building they built still stands as prime loft space in River Market area of KC. http://www.kcloftspace.com/richardsconoverlofts/)

Adding to the frustration of getting to the bottom of this story are several pages missing from Frank C. Wornall’s typed manuscripts at both the Wornall House and the Jackson County Historical Society. On top of that, the memoirs are the recollections of a nine-year-old boy writing some 70 years after the event. Everything should be taken with a small grain of salt.

Despite the paucity of hard evidence, my research tells me this story is completely believable. Troops under the Enrolled Missouri Militia were often locals with long standing scores to settle with Missourians. This region was the scene of the bloodiest most violent civilian insurrection in American history. Bushwhackers and Union troops regularly tortured, hung, scalped and defaced one another’s corpses and neither side was known for taking live prisoners. Regular army troops in pitched battles were different though. At least they were supposed to be.

I did find evidence of Confederate prisoners being executed at the Battle of Westport, but that event did not occur at the Wornall House. That happened after McGhee’s charge to capture Union cannons in what is now north Loose Park. That charge marked the high point of the battle and Price’s 1863 Missouri “expedition.” (During that charge there occurred an event rarely recorded in Civil War battles; two opposing officers shot and wounded one another with their sidearms.) The first charge initially failed, a later second charge captured the Union position and Confederates discovered the bodies of comrades who had been captured and then executed in the first charge. Were these the seven dead on the Wornall lawn and the source of the story of murder at Wornall? Are there motivations for stories such as this, true of not, to be propagated after the war?

I do not know the answers to these questions. I do know I will keep researching to learn what I can with the knowledge that a true mystery can never be solved…it can only be made a better mystery.