By Matthew Reeves

Every research subject has its own peculiar problems. Much of my previous research focuses on mental health issues in the nineteenth century America, and the records sometimes fall under the jurisdiction of federal health care privacy laws. Those laws impose certain restrictions on personally identifiable healthcare information, which in turn affects what types of sources are open to the public and what sources require special permissions. Our HistoryMakers internship project’s peculiar problem was my architectural literacy – as in, I didn’t have any!

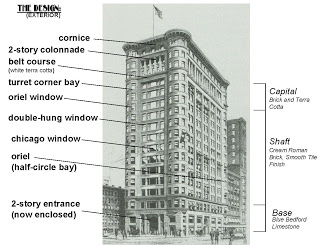

Graduate students tend to have fairly solid vocabularies, but it didn’t take me long to realize that I did not know how to describe, classify, and write about buildings. Sure, I knew about roofs, floors, and walls, and could even differentiate between brick and stone. What I could not do was talk about architecture’s finer points – cornices, entablatures, hip-roofs, muntins, and fenestrations were all a mystery to me. Clearly, I needed to keep my dictionary handy!

A Chicago School Skyscraper diagram from the excellent Chicago Textures architecture blog

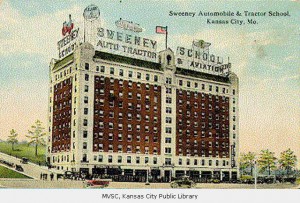

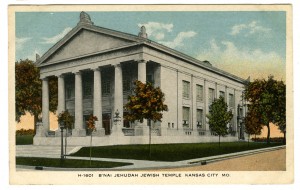

The best part about learning to describe architectural flourishes in technical terms was that my everyday life got much more interesting. Kansas City is full of complex, compelling, and diverse architecture. With my newfound lingo, I was able to read the City’s buildings in new ways, noting the architectural styles and thinking about their historical and visual context. Instead of seeing a building with a decorative front, I noticed its a structure with a façade; whereas before I saw a ledge-thingy, I now know that the decorative elements visually dividing the wall from rooftop are an entablature. Both façade and entablature came up a lot during my research: they’re common elements in Chicago-school neoclassical high rise design, a common style in downtown Kansas City.

Like a foreign language, learning a new professional lexicon is time-consuming. But my novice architectural vocabulary has expanded my world view by unlocking new and exciting elements in my everyday life. Buildings that I had passed without noticing now speak to me. Or, to put it another way, through my newfound architectural vocabulary I could hear the buildings for the first time.