Hello all!

My last post I talked about how I am almost finished with entering the entire collection into the museum’s collections management software. I can safely say that next week that will finally be finished. It is a bit relieving finally getting this task accomplished. When I first came to the American Royal almost two years ago, I had no idea the amount of work that was needed. After my first couple of weeks I quickly knew that I could not complete the task within the ten weeks I was initially hired for. I was working off a Microsoft Access database that was created in 2003 and was horribly outdated and was missing over 400 entries. I decided the only way to accomplish this task thoroughly was to go through each file individually and to ignore the Access database. Now I have entered just over 500 artifacts and when I am finished it should be closer to 525.

When I am finished with this I will start writing the action plan and organizing the collections storage areas available to me now. The end of the semester is quickly approaching, but everything is finally coming together.

Thanks for reading!

Philip Bland

My name is Kelly Hangauer. I am a senior at UMKC and I will be graduating with a History B.A. and German Studies minor in May 2015. This semester I am embarking on an archiving internship that will focus on the John B. Gage collection. So you know, John Gage was the mayor of Kansas City from 1940-1946 and was a part of the reform movement that “cleaned up” local government after years of economic and political misrule under Tom Pendergast. Housed in the Marr Sound Archives, Gage’s collection of records, cassettes, and reel-to-reel tape will hopefully offer greater insight into this important time in Kansas City history.

My name is Kelly Hangauer. I am a senior at UMKC and I will be graduating with a History B.A. and German Studies minor in May 2015. This semester I am embarking on an archiving internship that will focus on the John B. Gage collection. So you know, John Gage was the mayor of Kansas City from 1940-1946 and was a part of the reform movement that “cleaned up” local government after years of economic and political misrule under Tom Pendergast. Housed in the Marr Sound Archives, Gage’s collection of records, cassettes, and reel-to-reel tape will hopefully offer greater insight into this important time in Kansas City history. The second I walked into the Marr Sound Archives, I knew I had made the right decision. Inconspicuously placed in the bottom floor of the Miller Nichols Library, the Marr Archives is a gold mine; its contents include hundreds of thousands of recordings of popular and obscure music, government programs, radio broadcasts, oral histories…the list goes on.

The second I walked into the Marr Sound Archives, I knew I had made the right decision. Inconspicuously placed in the bottom floor of the Miller Nichols Library, the Marr Archives is a gold mine; its contents include hundreds of thousands of recordings of popular and obscure music, government programs, radio broadcasts, oral histories…the list goes on.

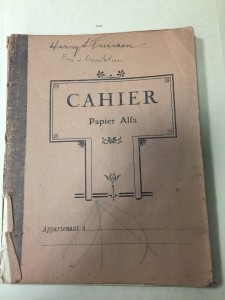

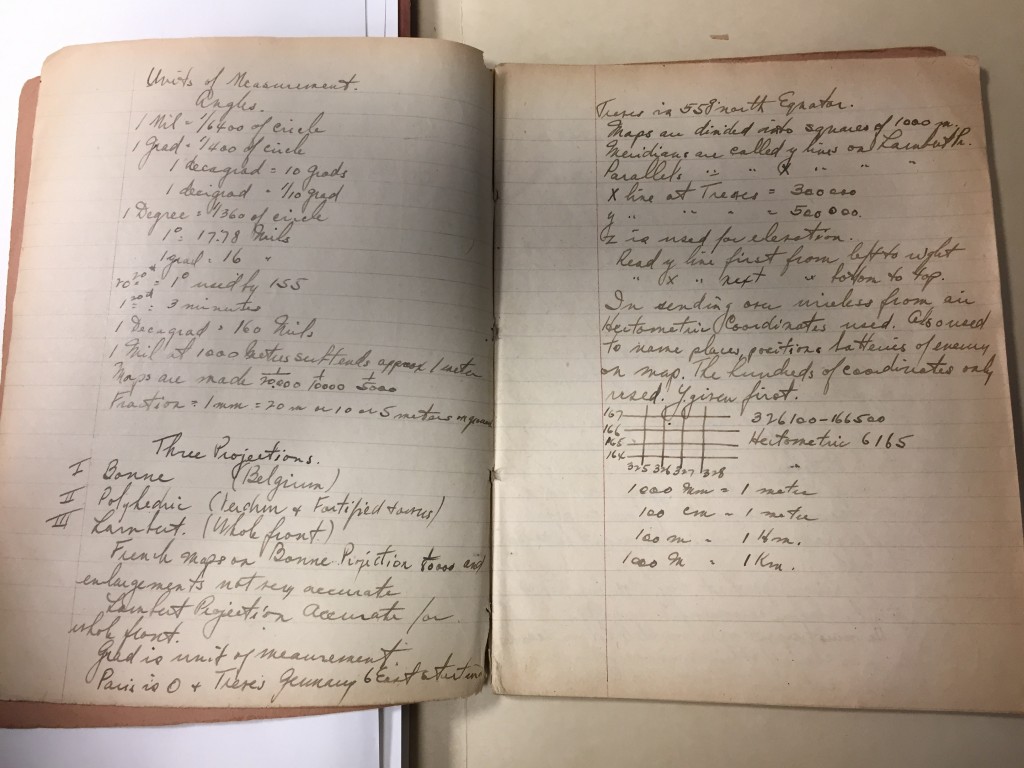

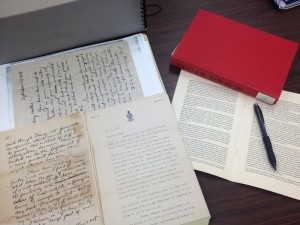

and can read cursive. The letters in this photo are pretty clear but there were some that were difficult to read.

and can read cursive. The letters in this photo are pretty clear but there were some that were difficult to read.