By Michael Sprague

These last few weeks have few weeks have been atypical for the Wyandotte County Museum. Shortly after University of Missouri – Kansas City closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the director informed all volunteers to work from home. Since the stay at home order, all museum staff is working remotely. It will be closed at least until the stay at home order is lifted and will likely remain closed until May. This has complicated my work for the institution, but I am still working on and revising two concurrent projects. Before the closure of the museum, I was able to collect some photographs for one of my projects, which I have now completed. Of course, this situation is not ideal for a variety of reasons. I was steadily building connections with historians of Wyandotte County, and the shelter-in-place order has unfortunately halted that. However, I am still committed to completing my work remotely.

Last month, I completed a game for high school and college aged students at the museum, which is focused on the community of Quindaro and its fight against Browning-Ferris Industries and the Kansas City, Kansas City Council. This is a topic which I am passionate about and intend to research going into my future graduate studies. The intersecting story of the fight against a proposed landfill in the Quindaro bluffs speaks to environmental and urban developmental histories and showcases the blatant disregard of the health of communities of color in the Kansas City era during the 1980s and 90s. The boom times of Old Quindaro are certainly fascinating and show the complexity and diversity of the Kansas City region’s history – but it seems that historians have marked the end of Quindaro’s history in the 1860s. What followed was the history of a burgeoning black community, which has largely been overlooked by historians and government officials alike.

Of course, Western University, the first black public school in Kansas, and arguably the first historically black college west of the Mississippi River is a fascinating story. I have devoted a significant amount of my undergraduate studies to the institution, and the impact that it had on the black community of Kansas City. This story has not been well told by local historians. Indeed, few laymen in the Kansas City areas know of its existence. Its history should absolutely be elevated into the public awareness, and the Wyandotte County Museum intends to create an exhibit dedicated to it at some point. Hopefully, with the resources I have available, I will be able to contribute to it.

I collaborated with the director of the museum to create an exhibit for Quindaro. The townsite was recently recognized as a National Commemorative Site, and the director wanted to draw attention to this in the museum. The exhibit provides background for the boomtown and its rapid decline, followed by a period of obscurity, and re-acknowledgement during the 80s and 90s. Photographs of the Quindaro ruins are limited – most structures were either stripped bare for firewood by Union soldiers during the Civil War, or succumbed to vegetation and erosion. However, there were some photographs of structures still standing in the 1910s and 20s.

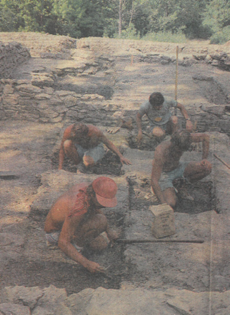

When Browning-Ferris Industries was required to fund a comprehensive archaeological survey for their proposed landfill site, few expected the ruins of a burgeoning city would be discovered. Truthfully, I do not fully understand why Quindaro’s history was so unknown at the time. Certainly, many Quindaro residents (such as Jesse Owens and Orrin M. Murray, Sr.) whose ancestors settled in the area knew what was there, but the ruins seemed to take everyone else by surprise, historians included. One archaeologist involved in the survey declared the townsite the “Pompeii of Kansas.” For more than one hundred years, the town that had contributed as a gateway for free state aid into the Kansas Territory, and as a haven for runaway Missouri slaves had been forgotten. I strongly suspect that Chester Owens was right when he said that no one knew about the history of Quindaro because no one valued the history of African Americans.

The final portion of the exhibit is dedicated to the effort to secure national funding for the Quindaro townsite. The goal is to highlight some of the effort by the community to preserve the ruins. It was not until 2002 that the townsite was registered on the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places. Unfortunately, since BFI withdrew their contract to construct a landfill, little has been done to further excavate the ruins, or to properly display what was uncovered in the 1980s. The passion was there, but the funding was not. Many are hopeful that the townsite’s recent designation as a National Commemorative Site will fund initiatives to further survey the ruins, and to display them in a more responsible manner. At this time, it is not clear how much the site will receive from the NPS, or what will be done with those funds. I ended the exhibit on a hopeful note, but in truth, I am more reserved in my optimism. Unfortunately, the endeavor to elevate Quindaro’s history has been contentious, and I do not see that changing any time soon. Circumstances would be better if the whole townsite were owned by the Unified Government of Wyandotte County, but unfortunately it must contend with the private owners of some of its property. In the interest of Quindaro’s history, I hope the community can finally come together to celebrate what the townsite represented, and its very real impact on freedmen and their descendants.

Thank you, very interesting and appreciated.

Marvin S. Robinson II

QUINDARO RUINS/ Underground Railroad- Exercise 2021