An ongoing conversation that is once again at the forefront of educator discussions comes in light of ESSA. According to EdWeek, ESSA continues to encourage schools to strengthen the ability of ELL families to engage meaningfully with schools about their child’s education. This fall Wendy Mejia, ELL Coordinator for Raytown School District, and Guadalupe Magaña, UMKC-RPDC MELL are piloting a family engagement program designed for parents and guardians who are also English language learners.

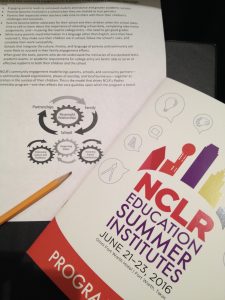

Preparations for the pilot began at the end of June 2016, when I accompanied Wendy Mejia to Fort Worth, Texas, for an invitational four-day training of trainers hosted by the National Council of La Raza (NCLR) to obtain certification in NCLR’s Padres Comprometidos (PC) model. PC is a tested and proven effective parent engagement program for parents and guardians who are also English learners. Guadalupe Magaña completed PC training shortly after her arrival at the UMKC-RPDC in July and brings a wealth of experience that will strengthen MELL’s capacity to offer PC to additional districts.

“I am excited to offer Padres Comprometidos to our Spanish-speaking secondary parents here in Raytown because it’s a great curriculum designed to give parents the knowledge and tools they need so that they can more fully engage with our district to be more actively involved in their children’s education. I think parents will learn so much! I look forward to working with Guadalupe Magaña to initiate the program here.” — Wendy Mejia, ELL Coordinator, Raytown School District

PC is broken into three levels of programming to address the specific informational needs of families of kindergarten, elementary, and secondary students. The grade-specific design of PC is a major factor of its success. The different tool kits take into account the differences in the “language” educators use to discuss student performance during parent-teacher meetings, for example. But PC addresses much more than parent-teacher conferences. Its design contains highly relevant information for families who need English language support while also increasing their understanding of how to navigate school protocols, engage with school personnel, and advocate effectively for their student’s academic success. All PC materials are available in English and Spanish which makes the training materials and the parent/guardian materials easily accessible for districts with higher concentrations of Spanish-speaking families.

Guadalupe has also embraced the training and the project with enthusiasm. After completing training, she expressed her passion for this initiative:

“Padres Comprometidos is here to make a change in the Hispanic families. The goal of this program is to motivate parents to [encourage] their children to go to college by building communication between school and parents, and understanding what is needed to go to college.” – Guadalupe Magaña, UMKC-RPDC MELL Instructional Specialist

Raytown School District is further supporting the implementation of the first PC cohort with provisions for day care, refreshments, and supplies. All of which demonstrates the district’s sensitivity to creating a welcoming environment for families, and underscores the district’s commitment to fostering parent engagement and family participation. Dr. Janie Pyle, Associate Superintendent of Curriculum Instruction and Assessment, Raytown School District, commented,

“This will support parent involvement activities for our ESL families.” –Janie Pyle, Associate Superintendent, Raytown School District

Watch for an announcement communicating the date for Guadalupe to provide additional information at a 2016-2017 ELL Consortium meeting (date to be set). She and Wendy will also share updates about how the pilot is progressing in Raytown.

Based on the anticipated success of Raytown’s first parent cohort, Guadalupe is looking for two additional districts who are also willing to host a cohort during the 2016-2017 school year. To find out more about PC and discuss the requirements for hosting a cohort of parents/guardians in your district, please email Guadalupe Magaña, maganag@umkc.edu.

In 2015-2016 the KCMELLblog featured the ELL parent digital literacy efforts at Center School District. If you have an effective family engagement practice or model to share, please scroll down to the “Leave a comment” button and share your ideas! We would love to feature your district’s great work in a future blog post. You may also share by emailing Diane Mora, morad@umkc.edu