By Elizabeth Perry

In 1975, Holocaust survivor Jack Mandelbaum was outside his home in Kansas City playing basketball with his family. A neighbor of theirs came over to chat – he was a nice guy, Jack remembered. He knew that Jack had survived the holocaust, had been in a concentration camp, and so asked, “What kind of sports did you play in the concentration camp?” Shocked, Jack looked back at him and said, “The sport was that the Nazis were trying to kill me and I was trying to stay alive.” Mandelbaum could not believe the lack of knowledge people had of what really happened, of the effects of the Holocaust. And so in 1993 he helped found the Midwest Center for Holocaust Education (MCHE) in order to spread this information. Ignorance, as Jack knew, was dangerous.

A couple of weeks ago, a story in the news brought Mandelbaum’s words back to me. On April 13, 2014, Frazier Glenn Cross drove to the Jewish Community Center, where the MCHE is located, and Village Shalom retirement community in Overland Park, where he shot and killed three people. The Overland Park police announced that this act is considered a hate crime, with Cross shouting “Heil Hitler” as he was arrested. His apparent intention in this attack was to kill Jews, but none of the three victims he shot were Jewish.

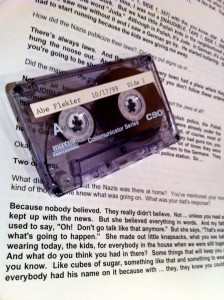

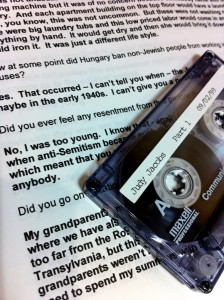

For the past three and a half months, I have been interning at the MCHE, transcribing testimonies of Holocaust survivors like Jack and helped correct transcripts of the interviews to make them available for the MCHE’s website. As I watched the news reports from the Jewish Community Center, I felt frustrated. I had spent my internship listening to survivors for whom the persecution and loss of their past is still present and haunting. Some of them are the only surviving members of their family. Each survivor interview I listened to had a standard format, ending each time with the question, “What can we learn from the Holocaust?” So many times, the interviewee said we must learn to be tolerant, respect others, and be compassionate, so that this kind of tragedy can never happen again. For a moment, as I watched the news of the shooting, I felt as if I had stepped backward and nothing had changed. But, perhaps it only proves how important it is to make the consequences of destructive hatred known. Continue reading

Beginning this summer, the

Beginning this summer, the